Anne Smedinghoff Didn’t Have to Die Part 2

[ Last week, Zen hosted Pete Turner’s guest post, PRT and State Department Ignorance Fails Us All. Here is part 2 of that article — posted by Charles Cameron for Zen ]

.

**

Last week I wrote about the tragedy of Anne Smedinghoff, who died on a patrol in Qalat Afghanistan. This is part 2 of the story–

My intention here is to illustrate HOW? rather than “what” we (Dr. Rich Ledet and I) did regarding the proper means to improve education in rural Afghanistan. I submit that our method is more reliable, predictable, measurable and can be replicated; yay scientific method.

Dr. Ledet and I leveraged an unusually strong partnership with a key Afghan political-religious leader. More than simply believing that we had a great relationship, we’d taken steps to build and validate the strength of our partnership, leveraging tools I had personally developed over years of immersion in conflict environments.

To begin with, we avoided the common US “crutch” of dominance, never assuming that we were “in charge.” Not only did we share many meals and tea with him, but we socialized with him and his family apart from any other American military elements. We also invited this leader to our dining facility to eat with us on numerous occasions. We shared our relevant reports (normally made for US elements only, these reports dealt with our evaluation of his region) with him (unclassified or FOUO) so that he could better understand our role and how the US was attempting to support him–This post is long enough already. I’ll have to come back to this particular topic later.

As a side note, I thought I had a great relationship with this leader after working with him almost daily for months. One day, he sat back, put his hand above his head and said, “I get what you are doing now. I understand that you are truly helping me with the Americans.” This breakthrough was surprising, as I thought we already had a good partnership. But I had misjudged what was previously accomplished, and the lesson I learned was that not only is trust VERY hard to earn, but also that there are different forms of trust to be accounted for when attempting to partner with leaders in conflict environments. Only after this point did I realize that I had earned an additional level of trust, and that he allowed me more latitude and access than he afforded any other American. In fact, I could come to him for advice, as he knew that I was genuinely working to support the Afghans in a way that was within the bounds of their customs.

We brought our research problem regarding education to our partner, and asked him how to best work toward a solution. He immediately identified the other elders with whom we needed to discuss and work, while providing us with the new Provincial Minister of Education’s (MoE) personal phone number (which we did not previously have on record) and advised us to mention his name when we talked. He noted that he was also attempting to work with the MoE on education in his district, and although they hadn’t always agreed, he felt the MoE was an honest man.

This process of partnering, and acquiring information about other leaders and the MoE, demonstrated a measure of trust indicating that our partner indeed valued us and our efforts. Further his validation through providing us with an introduction to other key decision-makers in the province which gave us unique access to a set of leaders that didn’t typically interact with US elements. We had truly entered through a more culturally appropriate door, as our partner trusted that we would not expose him in a negative light to the other leaders.

Once we were able to make contact with the recommended leaders, we were careful to explain the agenda, set up appointments, and accommodate their schedules as best as possible. We never showed up unannounced, or uninvited. With the safety of all involved in mind, we took time to determine their preferred place of meeting, which was critical considering that we lived on an American forward operating base, and could move in heavily protected convoys. We were remarkably “safer” than those leaders, as they lived in constant threat. We displayed a respect for their safety when we considered their venue preference. While these logistical steps seem obvious, we found this level of respect nonexistent in DoS, PRT and US forces attempting to work with local leaders, again relying on domination to achieve goals; US forces prefer to show up unannounced, unscheduled and take over the Afghan leader’s schedule as we set fit.

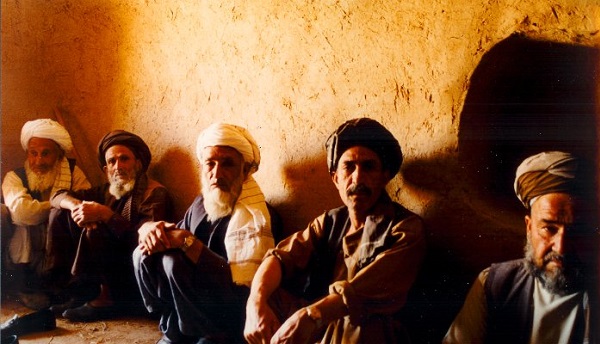

When we met, the recommended leaders were also accompanied by multiple religious elders. We didn’t ask them to do this, by the way, but it was something that was required in their culture. This was also an indicator to us that we approached the problem from the most culturally appropriate angle known to us (and recommended by our Afghan partner who originally set us up for success). Afghan leaders, when not influenced by Americans, will have a religious leader (mullah) present as they make decisions.

Over the course of several meetings, and after deliberation between the MoE and other family and religious leaders, we were able to ascertain what was expected in terms of US assistance. Keep in mind that what we were also doing was helping to link family, religious, and political leaders with a valid MoE backed plan to improve education throughout all of Zabul province; a critical element of creating stability wins.

These leaders never asked for money. They never asked us to build another school. They recognized that we could help, and they also wanted us to help them determine if these programs were working. They knew we had the capacity, which they knew they did not, to help them measure the success of the program.

What is most telling is that these leaders noted a lack of security, which is a common theme throughout my time in conflicted areas. Security concerns are superior, and every other effort is subordinate. This is where you need to pay attention DoS–The MoE asked that he never be seen engaging with the US at his office, as US patrols could only expose him to harm, he and other leaders wanted to reduce the amount of contact between US forces and their children for the same reason. Moreover, leaders in the district wanted us in the background, as they wanted to see the Afghan government and the MoE doing their job. They wanted the people living in Zabul Province to see the same–This is setting the stage for believable, culturally based stability win…and there is no photo op.

Our work established the beginnings of a clear plan that meets the requirements for creating stability. It satisfies a test we developed that indicates potential success when conducting non-lethal missions or operations…Is the operation Afghan inspired, Afghan led, Afghan provisioned, and sanctioned by a Mullah?

Is it possible that if DoS had bothered to teach Anne this test or heed our report, that she would still be alive?

March 30th, 2016 at 4:30 pm

No doubt she would have been alive had the imbeciles listened. The idiot ambassador got his press secretary killed for some kind of vanity project.

She was clearly a rising star in the ranks. It says on her wikipedia page that she escorted Kerry around Kabul during his visit just a couple weeks prior to her death.

Maybe she got this doomed assignment because she was expected to repeat that high profile assistance for her underling boss? I guess we’ll never know

.

Regardless of how badly the diplomats botched it, the security was inexcusable.

This was from the army report in one of the links from part 1:

.

“They were caught in the initial blast at about 11 a.m., when a remote-controlled bomb hidden under a pallet that was leaned up against the base’s southern wall detonated.

Five to 10 seconds after that initial blast, a man driving a blue Toyota — who the report states had been shooed away from the gate when the group was leaving the base — drove within the formation of soldiers and civilians and blew up his car, gravely injuring Smedinghoff, the interpreter and the three soldiers, among others”

.

She was killed right outside the base.

The Guardian article said it wasn’t uncommon to “walk short distances near bases where security is considered relatively good, particularly when there are checkpoints on access roads and US spy blimps that can survey the area around the clock.”

I suppose the spy blimps must have been grounded that day. My question for Pete is how often did you stroll around Qalat?

March 30th, 2016 at 8:37 pm

I didn’t cover the tactical portions of the story for a few reasons…I will say this. The imminent threat of a large scale attack was known. The PRT detail missed their “pattern of life” indicators–there is NEVER going to be a pallet leaned up against anything. A pallet to us is junk…to an Afghan that’s a pile of money just left about. Given the day’s threat assessment…the known presence of a VBIED cell…then the pallet…that right there should have changed the nature of that patrol. I could go on, but that is a different post. Bottom line…they never should have been on that particular patrol.

Someone used their rank/influence to ensure that mission happened and that changed the tactical decision making…