In memoriam: a tipi and a garden, II

Tuesday, May 29th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — Memorial Day, USA ]

.

2. The garden:

The Chelsea Flower Show is one of the minor Great British Occasions — a stroll in the park with some of the Kingdom’s finest horticulturalists displaying their best, and not usually the place you’d go to be reminded of war, though the show itself does take place in the grounds of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, the home of the Chelsea Pensioners…

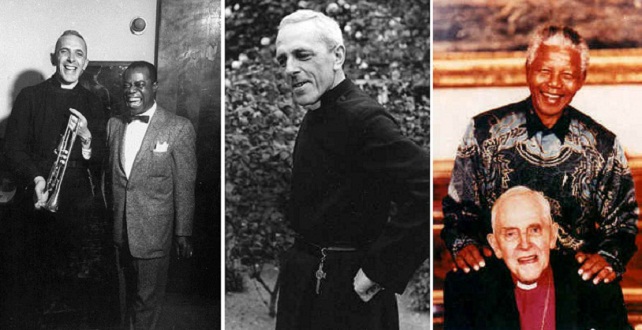

It is only appropriate, then, to find this picture of Skippy, a Pensioner from the Korean War, with Korean designer Hwang Ji-hae, whose garden this year won a gold medal for its representation of the DMZ between North and South Korea…

with its abandoned watchtowers and partially overgrown barbed-wire fences…

its bottles, carrying messages from those on one side of the line to friends and family unreachable on the other…

its benches made of wood and dog-tags, its memories…

and the wildflowers that have been taking over the DMZ, reasserting nature’s primacy where men’s wars were fought.

*

Hwang Ji-hae named her garden Quiet Time: DMZ Forbidden Garden:

This year’s “DMZ Forbidden” garden is “going to be a symbolic place honoring everyone who suffered because of the war,” Hwang said in an interview with the Korea JoongAng Daily in December in her studio in Gwangju.

The garden is a recreation of the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea, which has been kept nearly untouched for six decades since the 1953 Armistice Agreement. The zone has become a diverse habitat for various kinds of rare plants and animals.

To Hwang, the DMZ has become the “most beautiful garden on the planet,” though it symbolizes the legacies of the war and the tragic division of the Korean Peninsula at the same time, the artist said in the interview.

“The DMZ was formed organically after a major upheaval. It was created because of the war but is now a symbol of peace.”

According to a press release issued by Hwang’s agency on Tuesday night after winning the prize, 60 percent of the plants in the “DMZ Forbidden” garden are from Korea and some of them are indigenous to the DMZ area.

Hwang said that some of the British veterans of the Korean War she met last year talked about plants they saw in Korea, and they asked her to find them.

“There are six plants that are indigenous to the area near the DMZ, including Geumgang chorong [a type of bellflower], and they will all be part of the garden I’m creating,” she said during the interview in December.

“This is my way of thanking the veterans.”