[ by Charles Cameron – extended analytic game on Israeli-Palestinian conflict ]

.

In two previous posts (Intro, and Board and Gameplay), I have described my forthcoming attempt to “play” a 130-plus move game, in which I will use quotations, images and anecdotes to express something of the complex weave of thoughts and emotions that govern — in tense and tenuous fashion — the “Israeli-Palestinian problem”.

Here I will commence play, making my initial “moves” in this area of the board:

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Move 1: The Said Symphony

Move content:

When you think about it, when you think about Jew and Palestinian not separately, but as part of a symphony, there is something magnificently imposing about it. A very rich, also very tragic, also in many ways desperate history of extremes — opposites in the Hegelian sense — that is yet to receive its due. So what you are faced with is a kind of sublime grandeur of a series of tragedies, of losses, of sacrifices, of pain that would take the brain of a Bach to figure out. It would require the imagination of someone like Edmund Burke to fathom.

Edward W. Said, Power, Politics, and Culture, p. 447 — from the section titled “My Right of Return,” consisting of an interview with Ari Shavit from Ha’aretz Magazine, August 18, 2000.

Links claimed:

In his novel of the Glass Bead Game, Hermann Hesse writes:

Every transition from major to minor in a sonata, every transformation of a myth or a religious cult, every classical or artistic formulation was, I realized in that flashing moment, if seen with a truly meditative mind, nothing but a direct route into the interior of the cosmic mystery, where in the alternation between inhaling and exhaling, between heaven and earth, between Yin and Yang, holiness is forever being created.

It is in the links between moves, the creative leaps of the analogical mind, that the secret of the game can be found — so the “links claimed” sections of moves can be viewed as meditation points — architecturally, they are the “arches” of potential insight between the “pillars” of existing ideas. Here, no links are claimed, since this is the first move in the game.

Comment:

This is where it begins… with a vision of dissonant voices in counterpoint… ____________________________________________________________________________________________

Introductory moves

Before we get directly into the “meat” of the game, I want to explore its purpose via a few more moves that focus on what we might call the polyphony of ideas — thinking in terms of multiple voices.

Move 2: Hermann Hesse and the Glass Bead Game

Move 3: JS Bach and the Art of Fugue

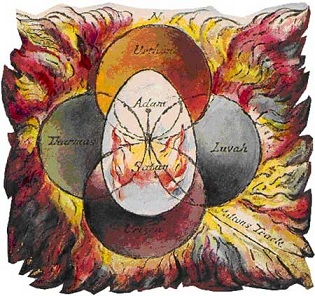

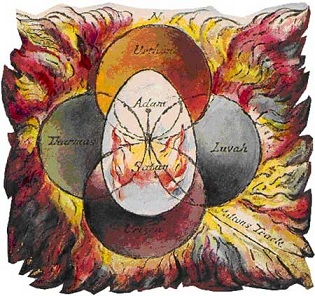

Move 4: William Blake and Fourfold Vision

Move 5: Bob Dylan and One Too Many Mornings

Move 6: Glenn Gould

Then two moves nudging us in the direction of, then directly into — Israel:

Move 7: Daniel Barenboim

Move 8: Wagner

and specifically to the outskirts of Jerusalem / Al Quds:

Move 9: Golgotha

You might want to consider these nine moves a sort of overture. Let’s see how that goes…

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Move 2: Move 2: Hermann Hesse and the Glass Bead Game

Move content:

Hermann Hesse’s novel Das Glasperlenspiel (English title The Glass Bead Game, also published as Magister Ludi) won him the Nobel for Literature.

The centerpiece of the novel is the Game itself. Hesse doesn’t spell out in detail how it is to be played, but his hints are enough to let us know that in play, different ideas from across world culture are combined as if in a virtual music of ideas:

The Glass Bead Game is thus a mode of playing with the total contents and values of our culture; it plays with them as, say, in the great age of the arts a painter might have played with the colors on his palette. All the insights, noble thoughts, and works of art that the human race has produced in its creative eras, all that subsequent periods of scholarly study have reduced to concepts and converted into intellectual values the Glass Bead Game player plays like the organist on an organ. And this organ has attained an almost unimaginable perfection; its manuals and pedals range over the entire intellectual cosmos; its stops are almost beyond number.

It is in an attempt to bring Hesse’s idea of a musical synthesis of ideas into practical application in helping us understand — and perhaps even, god willing, help us to resolve — the Palestinian-Israeli conflict that I am playing this game.

The idea is not to come up with a solution, but a richer sense of the interplay of motives and memories as they build the situation we all now face.

Link claimed:

To Edward Said, in that Hesse immediately precedes Said in his intuition that melodies are not the only kinds of thought that can be juxtaposed in counterpoint and thus integrated in a complex, sometimes tragic, often profound, always human music.

Comment:

The graphic I have used is from the cover of a lovely CD, featuring Arturo Delmoni and Nathaniel Rosen, Music for a Glass Bead Game. ____________________________________________________________________________________________

Move 3: Move 3: JS Bach and the Art of Fugue

Move content:

Bach was my first great love in the arts, and when I applied to study at Christ Church, Oxford, it was essays on Hopkins, El Greco, and Bach — specifically the B Minor Mass — that got me in the door. Years later, when I lived in Warrenton and commuted to a think-tank job in Arlington, VA, I found myself muttering To hold the Mind of Bach over and over to myself like a mantram.

And that, I think, is the key to my games.

I want to think as Bach did, polyphonically — to see the world in terms of counterpoint, to read life musically. And my games, which involve holding related, sometimes harmonious and sometimes conflicting thoughts in the mind at the same time, invite and encourage me to do that. They also provide me with a method of notating (scoring, in the musical sense) such multi-thought patterns on the various HipBone boards.

It is Bach, therefore, who is grandfather to Said’s thought, as Hesse is its father — and Bach’s greates expressions of this approach are found in such great summary works as the B Minor Mass and the Art of Fugue.

The taste I offer here is from Contrapunctus IX, which you can hear played by Glenn Gould on the organ here (and download it for 99 cents)…

Links claimed:

To Hesse and the Bead Game, because Bach’s presence, and that of counterpoint whose greatest exponent he was, is fundamental to Hesse’s great Game. Indeed, as he writes in the book:

The Game was at first nothing more than a witty method for developing memory and ingenuity among students and musicians. … One would call out, in the standardized abbreviations of their science, motifs or initial bars of classical compositions, whereupon the other had to respond with the continuation of the piece, or better still with a higher or lower voice, a contrasting theme, and so forth. It was an exercise in memory and improvisation quite similar to the sort of thing probably in vogue among ardent pupils of counterpoint in the days of Schütz, Pachelbel, and Bach — although it would then not have been done in theoretical formulas, but in practice on the cembalo, lute, or flute, or with the voice.

To Edward Said and his call for a symphonic reading of the Israeli-Palestinian situation: because he invokes the mind of Bach himself in the passage quoted in move 1, speaking of the

sublime grandeur of a series of tragedies, of losses, of sacrifices, of pain that would take the brain of a Bach to figure out.

Comment:

It is said that every artist teaches us to see, listen, hear, read, understand in a fresh way, so that the artist’s own work, at first well-nigh incomprehensible, may gradually find its way first into clarity, and then into ease of access, obviousness, popularity, and “classical” status — later stages of the same process will bring it first obscurity and finally oblivion.

We are not yet in a position to hold many thoughts simultaneously in the mind as Bach’s mind held many melodies, but we are opening to the possibility…

Multi-tasking… this will be an early attempt at a game of musical multi-thinking. Please think it through with me… ____________________________________________________________________________________________

Move 4: William Blake and Fourfold Vision

Move content:

Here’s what William Blake saw:

Here’s what William Blake said, in his Letter to Thomas Butts:

Now I a fourfold vision see

And a fourfold vision is given to me

Tis fourfold in my supreme delight

And three fold in soft Beulahs night

And twofold Always.

May God us keep\

From Single vision & Newtons sleep.

Here’s a commentary on Blake’s notion from a fascinating paper by Marcel O’Gorman:

Several Blake critics have attempted to unravel Blake’s use of term “fourfold vision.” Accoring to Jerome McGann, beings of single vision see the world in absolutes. Life is a prison term that ends in a final, discrete annihilation. Men of twofold vision see the world dialectically, according to contraries. Threefold vision enables one to recognize the contraries and see that they are not absolute, but that the boundaries of good and evil shift according to each individual. In Milton, Blake defines threefold vision as a peaceful state, and he associates it with Beulah:

There is a place where Contrarieties are equally True This place is called Beulah, It is a pleasant lovely Shadow Where no dispute can come. Because of those who Sleep. (M 30:1-3)

Beulah and threefold vision are identified with sleep, restfulness. But fourfold vision involves activity, not sleep. Fourfold vision is generation and destruction, life and death, or even life in death. Evidently, Blake’s understanding of death is unconventional, to say the least. For Blake, death is considered as part of the creative process, a part of life.

Links claimed:

To the Glass Bead Game: because Hesse writes:

I suddenly realized that in the language, or at any rate in the spirit of the Glass Bead Game, everything actually was all-meaningful, that every symbol and combination of symbols led not hither and yon, not to single examples, experiments, and proofs, but into the center, the mystery and innermost heart of the world, into primal knowledge. Every transition from major to minor in a sonata, every transformation of a myth or a religious cult, every classical or artistic formulation was, I realized in that flashing moment, if seen with a truly meditative mind, nothing but a direct route into the interior of the cosmic mystery, where in the alternation between inhaling and exhaling, between heaven and earth, between Yin and Yang, holiness is forever being created.

Yin and yang are the opposites of the dialectic, but in the yin-yang symbol or tai-chih we see them alternating and interpentrating in the subtle and fluid play between them (Blake’s threefold vision) from which, in Hesse’s words, “holiness is forever being created” — Blake’s fourth.

To the Said Symphony, because precisely that kind of fluid flowing between one perspective and another is what allows empathy to triumph over opposition, and the “other” to become “brother” — the condition in which alone “the peaceable kingdom” / “peace on earth” can prevail…

Comment:

Blake was the mentor of my own poetic mentor, Kathleen Raine, and my own early published poems appeared in a Penguin volume edited by Michael Horovitz and titled Children of Albion in Blake’s honor.

I am happy to remember such friends in writing this game — and amazed to find in the Blake illustration above, which I only ran across today in O’Gorman’s article, yet another visual precursor to the boards on which my games are played. ____________________________________________________________________________________________

Move 5: Bob Dylan and One Too Many Mornings

Move content:

The Bob Dylan song, One too many mornings.

You’re right from your side

I’m right from mine

We’re both just one too many mornings

An’ a thousand miles behind

Links claimed:

To Fourfold Vision and William Blake: Dylan captures the utterly wrong double-rightness of conflict that features in Blake’s vision — at an intensely personal level. And I’d argue, personally, that Dylan does in music and poetry what Blake was doing in poetry and visual art — at greater depth than his Blakean friend (and companion on parts of the Rolling Thunder tour) Allen Ginsberg.

Comment:

I believe I was at the Colorado Rolling Thunder Revue concert where Dylan sang the version which YouTube presents here from a Japanese bootleg video tape. You can purchase the Hard Rain album — or just the one track — here. ____________________________________________________________________________________________

— four more moves coming up shortly in a follow-up post, and then I’ll take a break.