On getting it right, eh?

Thursday, April 25th, 2013[ by Charles Cameron — with a little help from the Buddha, fake quotes, self-referential paradox, a pinch of salt, and two tbsps of anthropology ]

.

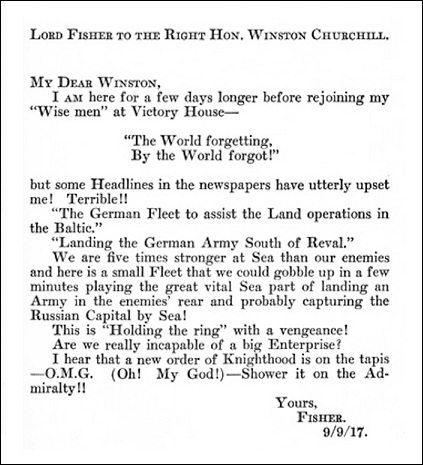

Over the last ten days we have seen a whole lot of speculation, misinformation, spin and gossip masquerading as analysis and journalism, and that was on my mind when I ran across an alleged Buddha-quote that told me to use my common sense — and since my common sense told me there probably wasn’t a phrase in Pali, the language of the earliest Buddhist texts, that would correspond too closely to the highly idiomatic English usage, common sense, I thought I should check it out with Fake Buddha Quotes, my go-to place for checking what the Buddha is supposed to have said:

I’m pretty sure the Buddha never said “Pretty sure I never said that” too, for much the same reason.

**

But what delights me most about all this is just how self-referential this all is: the Buddha allegedly warns us against trusting what we read even when it’s attributed to him, in what turns out to be a faux quote attributed to him, based on a real quote that reads (in one translation):

Any teaching should not be accepted as true for the following ten reasons: hearsay, tradition, rumor, accepted scriptures, surmise, axiom, logical reasoning, a feeling of affinity for the matter being pondered, the ability or attractiveness of the person offering the teaching, the fact that the teaching is offered by “my” teacher. Rather, the teaching should be accepted as true when one knows by direct experience that such is the case.

**

Fpr what it’s worth, the abbreviated version doesn’t mean the same as the original. From Koun Franz at Sweeping Zen:

his is a very different idea. The original says we need to verify through direct experience; the popular version says that we can stand back from the practice, at a distance, and use reason to determine its authenticity.

Or this, from Bodhipaksa, the Fake Buddha Quotes guy, :

The Buddha of course isn’t saying we should jettison reason and common sense. What he’s implying is that both those things can be misleading and what’s ultimately the arbiter of what’s true is experience. It’s when you “know for yourselves” that something is true through experience that you know it’s true.

**

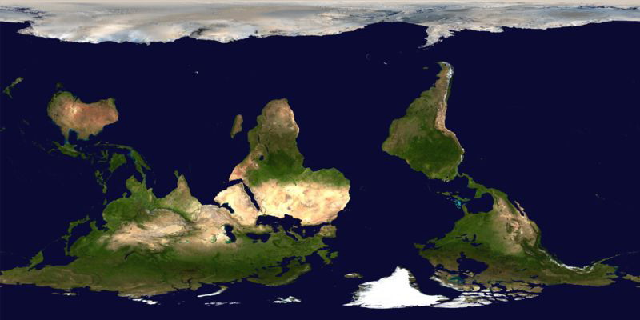

Another comment on the same page led me to this first comment on cultures and languages —

which in turn reminded me of the second, a long-time favorite of mine from the time when I was some sort of Anthro professor in dreamy Oregon…

**

And, y’lnow, both those quotes in my second pair give you a visceral sense of what today’s SWJ article by Robert R. Greene Sands and Thomas J. Haines, Promoting Cross-Cultural Competence in Intelligence Professionals is very rightly on about, though it’s all phrased in a manner so abstract you might easily miss the point…

Mitigating cognitive, cultural and a host of tradecraft biases is essential for intelligence professionals to navigate through today’s culturally complex environments. Adopting the perspective of contemporary cultural groups, including nation-states, often defies understanding because the intelligence professional is challenged to both appreciate and consequently discern meaning of behavior that is predicated on vastly different beliefs and value systems. Fundamental to this dissonance is a markedly different cultural reality resulting from different histories, traditions and the stasis of culture. The professional’s western and deeply seated worldview impedes either the analysis itself, or is perjured by the cognitive restrictions imposed by the structured analytic strategies used.

The quote about the Wintu — it’s from Dorothy Lee, Linguistic Reflection of Wintu Thought, Chapter 9 in Dennis and Barbara Tedlock‘s Teachings from the American earth: Indian religion and philosophy — goes on to say:

The Wintu relationship with nature is one of intimacy and mutual courtesy. He kills a deer only when he needs it for his livelihood, and utilizes every part of it, hoofs and marrow and hide and sinew and flesh. Waste is abhorrent to him, not because he believes in the intrinsic virtue of thrift, but because the deer had died for him.

Now there‘s “a markedly different cultural reality” for you!