History Will Judge Only if We Ask the Right Questions

Thomas Ricks of CNAS recently had a historically-minded post at his Best Defense blog at Foreign Policy.com:

What Tom would like to read in a history of the American war in Afghanistan

I think I’ve mentioned that I can’t find a good operational history of the Afghan war so far that covers it from 2001 to the present. (I actually recently sat on the floor of a military library and basically went through everything in its stacks about Afghanistan that I hadn’t yet read.)

Here are some of the questions I would like to see answered:

–What was American force posture each year of the war? How and why did it change?

–Likewise, how did strategy change? What was the goal after al Qaeda was more or less pushed in Pakistan in 2001-02?

–Were some of the top American commanders more effective than others? Why?

–We did we have 10 of those top commanders in 10 years? That doesn’t make sense to me.

–What was the effect of the war in Iraq on the conduct of the war in Afghanistan?

–What was the significance of the Pech Valley battles? Were they key or just an interesting sidelight?

–More broadly, what is the history of the fight in the east? How has it gone? What the most significant points in the campaign there?

–Likewise, why did we focus on the Helmand Valley so much? Wouldn’t it have been better to focus on Kandahar and then cutting off and isolating Oruzgan and troublesome parts of the Helmand area?

–When did we stop having troops on the ground in Pakistan? (I know we had them back in late 2001.) Speaking of that, why didn’t we use them as a blocking force when hundreds of al Qaeda fighters, including Osama bin Laden, were escaping into Pakistan in December 2001?

–Speaking of Pakistan, did it really turn against the American presence in Afghanistan in 2005? Why then? Did its rulers conclude that we were fatally distracted by Iraq, or was it some other reason? How did the Pakistani switch affect the war? Violence began to spike in late 2005, if I recall correctly — how direct was the connection?

–How does the war in the north fit into this?

–Why has Herat, the biggest city in the west, been so quiet? I am surprised because one would think that tensions between the U.S. and Iran would be reflected at least somewhat in the state of security in western Afghanistan? Is it not because Ismail Khan is such a stud, and has managed to maintain good relations with both the Revolutionary Guard and the CIA? That’s quite a feat.

Ricks of course, is a prize winning journalist and author of best selling books on the war in Iraq, including Fiasco and he blogs primarily about military affairs, of which Ricks has a long professional interest and much experience. Ricks today is a think tanker, which means his hat has changed from reporter to part analyst, part advocate of policy. That’s fine, my interest here are in his questions or rather in how Ricks has approached the subject.

First, while there probably ought to be a good “operational history” written about the Afghan War – there’s a boatload of dissertations waiting to be born – I think that in terms of history, this is the wrong level at which to begin asking questions. Too much like starting a story in the middle and recounting the action without the context of the plot, it skews the reader’s perception away from motivation and causation.

I am not knocking Tom Ricks. Some of his queries are important – “What was the effect of the war in Iraq on the conduct of the war in Afghanistan?” – rises to the strategic level due to it’s impact and the light it sheds on national security decision making during the Bush II administration, which I suspect, will not look noble when it is revealed in detail because it almost never is, unless you are standing beside Abraham Lincoln as he signs the Emancipation Proclamation. Stress, confusion, anger and human frailty are on display. If you don’t believe me, delve into primary sources for the Cuban Missile crisis sometime. Or the transcripts of LBJ and NIxon. Exercise of power in the moment is uncertain and raw.

But most of the questions asked by Ricks were “operational” – interesting, somewhat important, but not fundamental. To understand the history of our times, different questions will have to be asked in regard to the Afghan War. Here are mine for the far off day when documents are declassified:

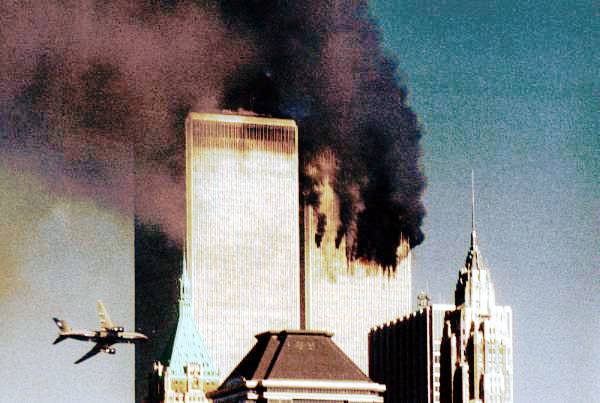

What was the evolution of the threat assessment posed by Islamist fundamentalism to American national security by the IC from the Iranian revolution in 1979 to September 11, 2001? Who dissented from the consensus? What political objections or pressures shaped threat assessment?

What did American intelligence, military and political officials during the Clinton, Bush II and Obama administrations know of the relationship between the ISI and al Qaida and when did they know it?

What did American intelligence, military and political officials during the Clinton, Bush II and Obama administrations know of the relationship between Saudi intelligence, the House of Saud and al Qaida and when did they know it?

What did American intelligence, military and political officials during the Clinton, Bush II and Obama administrations know of the relationship between the Taliban and al Qaida and when did they know it?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did Saudi leverage over global oil markets effect American strategic decision making?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did Pakistani nuclear weapons effect American strategic decision making?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did the “Iraq problem” effect American strategic decision making?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did nuclear terrorism threat assessments effect American strategic decision making? Did intelligence reports correlate with or justify the policy steps taken?

Who made the call on tolerating Pakistani sanctuaries for al Qaida and the Taliban and why?

Was there a net assessment of the economic effects of a protracted war in Afghanistan or Iraq made and presented to the POTUS? If not, why not?

Why was a ten year war prosecuted with a peacetime military and a formal declaration of war eschewed?

How did the ideological convictions of political appointees in the Clinton, Bush II and Obama impact the collection and analysis of intelligence and execution of war policy?

Who made the call for tolerating – actually financially subsidizing – active Pakistani support for the Taliban’s insurgency against ISAF and the Government of Afghanistan and why?

What counterintelligence and counterterrorism threat assessments were made regarding domestic Muslim populations in the United States and Europe and how did these impact strategic decisions or policy?

What intelligence briefs or other influences caused the incoming Obama administration to radically shift positions on War on Terror policy taken during the 2008 campaign to harmonize with those of the Bush II administration?

What discussions took place at the NSC level regarding the establishment of a surveillance state in the “Homeland”, their effect on our political system and did any predate September 11, 2001 ?

What were the origins of the Bush administration’s judicial no-man’s land policy regarding “illegal combatants” and “indefinite detention”, the recourse to torture but de facto prohibition on speedy war crimes trials or capital punishment?

The answers may be a bitter harvest.

April 18th, 2012 at 12:04 pm

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did the Iran problem affect American strategic decision-making? Especially with regard to your question, “Who made the call on tolerating Pakistani sanctuaries for al Qaida and the Taliban and why?”.

.

Yes to asking, and honestly and fairly delving into, all of these questions. Bravo, zen. Stellar post.

April 18th, 2012 at 12:11 pm

I’ve been collecting all sorts of interesting stuff regarding these questions. I am an everyday person, have no training in history or any subject like history, so I am sure I go off on the deep end sometimes. Here are some very, very, very rough attempts from me (and there are many more aspects as you point to in your post):

.

A link to the 2009 “Afpak” white paper which laid out our current strategy. Who was involved in crafting this white paper and the subsequent strategies? It wasn’t just McChrystal.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/27/us/politics/27text-whitepaper.html?pag…

April 18th, 2012 at 12:12 pm

More from me (and one comment is awaiting moderation in case this comment confuses readers : ) )

.

1. Old Cold War blocs including NATO and our Saudi-Pakistan alliance against Iran (one reason among many we continued to cultivate the military dictatorship of Musharraf, even when we knew that Al Q’s Taliban hosts were a creation of Pakistan’s government).

.

2. The Bush administration’s Cold War “habit as policy.” We had always worked with Islamabad and Rawalpindi in that part of the world. We assumed if we paid enough, they would do our job and we could invade Iraq. It’s not a surprise given that many in the Bush administration, to include Sec. Gates, were formerly members of the Nixon administration.

.

3. The continued ignoring of Saudi Arabia’s role in 9-11, even as we cultivate Qatar as a “baby” Saudi.

.

4. Western modernization and developmental theory leading to pop-COIN.

.

5. 90s neomercantalism as strategy and policy.

.

6. Centcom’s desire to have its old South Asian military relationships back?

.

7. The Obama administration’s desire to have good relations with “the Muslim” world, as if such a large and complicated world could be understood with childish and patronizing theorizing. We are not talking children, here, but adults.

.

8. A think tank and PhD community that had never questioned its own status quo thinking about Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the prominent defense sales lobby, to include other DC institutions hungering for more funding, include Pakistan and Afghanistan program funds.

http://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/cordesman-announces-death-of-a-strategy-in-afghanistan

And Vali Nasr to Johns Hopkins and the strategy community there? I’m not playing “gotcha.” I seek only understanding. No more, no less.

I see this as a team effort and a lot of teams, including everyday people like me, got misdirected.

April 18th, 2012 at 12:21 pm

You might find the following interesting, and then I will let up:

.

This episode, sadly, also raises some embarrassing questions which I have not read or heard asked about the West’s intel services. When I worked in Pakistan, and this was well before high-tech drones, Google, and all the rest of that stuff, somebody with our Embassy, or with our friends at the neighboring British High Commission, would have commented on this compound, and undertaken an effort to find out who lived there, how it was being paid for, etc.

.

http://thediplomad.blogspot.com/search?q=pakistan

.

It’s always been us that I have been interested in. It’s us, the US, that I’ve always been “studying,” although I am not sure that comes across sometimes. Other countries will do what they think is in their best interests. That is the world. It’s what we do that concerns me.

April 18th, 2012 at 1:54 pm

One big issue, I think, is that it’s too early for an unbiased retrospective that answers those questions – we’re too close to what happened. The really good books on Vietnam started coming out in the late ’70s and the lens it was viewed from really didn’t change until the 1990s. Later in this decade, I think, we’ll start seeing some thoughtful books covering these areas and twenty years from now we’ll have less biased (emotional?) views on what happened.

That’s my two cents, anyway.

April 18th, 2012 at 2:27 pm

Hi Zen,

.

The answers will be a bitter harvest, and I doubt many will ever be answered. The competing interests—regardless political party—are too numerous, and the answers would likely implicate high officials being stupid, or at worst tolerating/pretending to fight at the national level, while ham-stringing the military via ROE, etc.

.

I’ve heard many times that politicians should let the generals fight our wars, but politicians rarely resist the opportunity to do otherwise. Added to this, the highly politicized environment flag officers must navigate…competing interests are everywhere…which could make transparent answers to these question all but impossible.

.

Scott, you make a very good point on time and perspective.

April 18th, 2012 at 4:38 pm

Ricks is looking at operational questions, though — he says so explicitly at the start of the passage you quote. Operations should flow from strategy, but have different concerns. I agree that the strategic questions are essential for good history, but they’re also a level above how we fight. His interests and inclinations might reside naturally at the operational level, while an Army platoon commander might care most about tactics. All of them are valuable areas of exploration, and help build up a picture of historical “truth.”

“the light it sheds on national security decision making during the Bush II administration, which I suspect, will not look noble when it is revealed in detail because it almost never is, unless you are standing beside Abraham Lincoln as he signs the Emancipation Proclamation”

In my experience of foreign policy decision making, those in charge are frequently confronted with the dilemma of picking the least bad option. Often, there are no “good” choices. It’s hard to be noble under those conditions. And American national security interests might very well entail consequences that harm others. The responsibility of the leader is to at least be aware of those costs, and make a conscious choice to accrue them.

April 18th, 2012 at 7:28 pm

On reflection from “over here” I would add the following points, which apply to the USA and UK primarily and maybe to other ISAF allies:

1) When was there a coherent strategy and purpose in Afghanistan? Adding in Pakistan and other nations only acts to avoid answering this question.

2) After the initial success in 2001-2002 and the Bonn Agreement (to create a centralised state) when was it recognised the intervention was failing? Much is made in British reflections, prior to 2006, that Afghanistan was in danger of collapsing and attention turned to re-engaging the USA.

3) Was there ever an assessment of the disadvantages of a coalition approach on the ground? We know various non-US ownership of sector responsibility failed, notably in training the ANP and for example 90% of the German contingent never left their bases.

4) Given the known weaknesses of the Karzai regime and a central Afghan state, that are contemporary and historical, did we recognise and plan for upcoming key points in state-building?

5) Has the alleged ‘Murder by Doctrine’ followed since 2006 ever been reviewed strategically?

6) Given the dearth of intelligence in Afghanistan, for example in understanding the social complexion and tactical capability of likely opposing groups in Helmand Province in 2006, even after MG Flynn’s report have we ever understood the environment enough to wage war?

7) Has Afghanistan suffered from too many soldiers, too much technology, too few civilians on the ground and too much money. Would less, far less been better for Afghanistan and our national objectives?

8) What is the cost of a potential Taliban victory, whether via negotiation or after an ISAF / US exit?