Getting deeper into Koestler

Friday, March 18th, 2016[ by Charles Cameron — on creativity at the intersection of the fleeting and the eternal ]

.

Centaur, displayed in the International Wildlife Museum, Tucson, AZ

**

You know Lao Tzu’s “uncarved wood” (pu) — and Spencer Brown’s “Mark” or “first distinction? It is hard to speak of “the one and the many” without language itself favoring the many, the one being “one” and the many “another”. The Greek phrase “Before Abraham was, I am” attributed to Christ may be as close as we get.

The “uncarved wood” is not some definite -– named and thus defined -– “one” -– it is also “raw silk” (su), the simple -– the natural way or stream, from which things have not yet been separated out by naming.

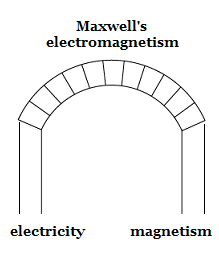

There is delight, however, both in one becoming two and thus many, in the making of distinctions and naming of names, and no less in two (or the many) becoming one, in the resolution of paradox, the release of tension, peace after strife. In human terms, there is joy in both solo and collaborative achievement.

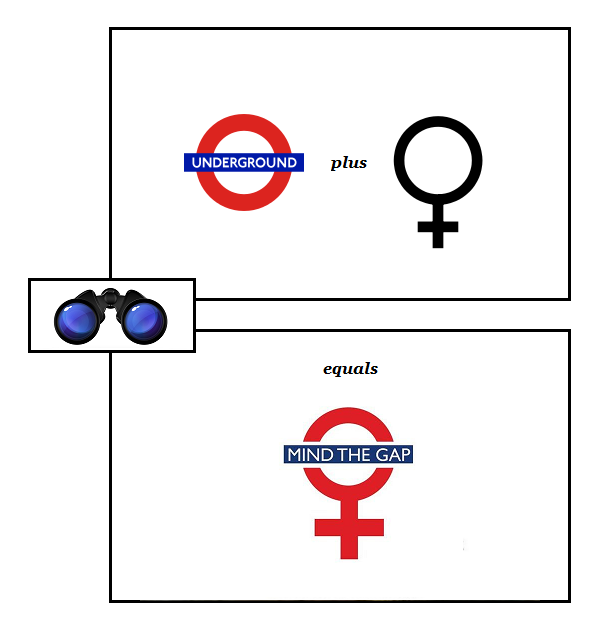

What better, then, than the perfect fit between disparate entities?

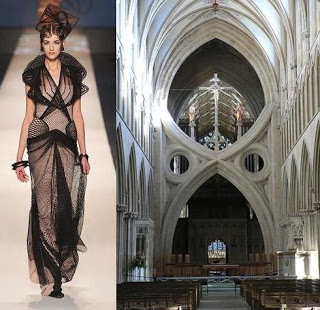

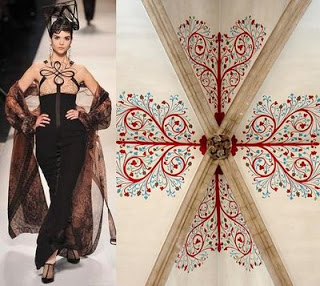

I have written often enough about Arthur Koestler and the place where two disparate spheres of thought link up — the centaur links horse and man in an indissoluble unity — there’s no question here of dismounting after a ride, giving the horse a rub down and some feed, then retiring to the verandah for a whiskey…

The mythological aha! we get from the centaur displayed in the museum hinges on the fit of horse and human skeletons, the perfection with which disparates are joined.

**

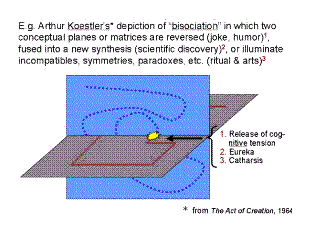

Thus far, whenever I’ve discussed Koestler‘s notion of bisociation, I’ve focused on the sense that it liea at the heart of creativity. Koestler himself takes it deeper. Here’s Nicholas Vajifdar, in a review titled Summing Up Arthur Koestler’s Janus: A Summing Up:

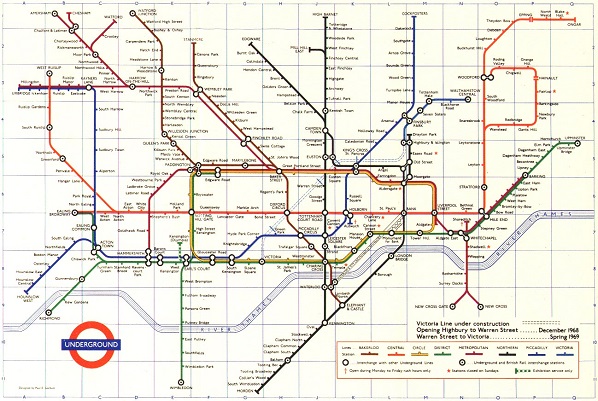

Koestler .. asserts that there are two planes of existence, the trivial and the tragic. The trivial plane is the stage for paying bills, shopping, working. Most of life takes place on the trivial plane. But sometimes we’re swept up into the tragic plane, usually due to some catastrophe, and everything becomes glazed with an awful significance. From the point of view of the tragic plane, the trivial plane is empty and frivolous; from the point of view of the trivial plane, the tragic plane is embarrassing and overwrought. Once we’ve moved from one plane to the other, we forget why we could have felt the way we used to.

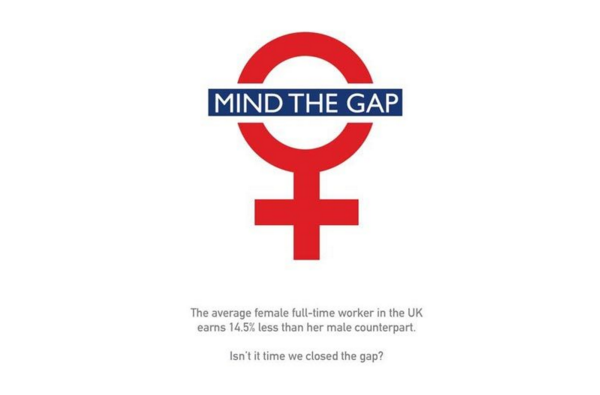

That’s not just any old distinction between two realms, that’s the one Koestler himself prioritizes. And following his basic principle that a creative spark is lit when two disparate “planes of ideas” intersect, we shouldn’t be too surprised to find Vajifdar continuing:

“The highest form of human creativity,” Koestler writes, “is the endeavor to bridge the gap between the two planes. Both the artist and the scientist are gifted — or cursed — with the faculty of perceiving the trivial events of everyday experience sub specie aeternitatis, in the light of eternity…”

William Blake made a similar observation in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, writing:

Eternity is in love with the productions of time.

Finally, Vajifdar tells us why he finds Koestler’s definition of art maybe the best he’s ever read:

What I value in this definition of creativity is its emphasis on the subjective being of those who experience the work of art or scientific theory, a surer gauge than cataloguing formal properties or whether it’s “interesting.” Art has always seemed like a kind of sober drunkenness, or drunken sobriety. Most people probably have wondered whether the feelings they felt while drunk were more or less real than their sober feelings. Koestlerian art joins these seemingly irreconcilable feelings together.

Let’s just go one step further. In Promise and Fulfilment – Palestine 1917-1949, Koestler specifically singles out this intersection as an aspect of the experience of warfare:

This intense and perverse peace, superimposed on scenes of flesh-tearing and eardrum-splitting violence, is an archetype of war-experience. Grass never smells sweeter than in a dug-out during a bombardment when one’s face is buried in the earth. What soldier has not seen that caterpillar crawling along a crack in the bark of the tree behind which he took cover, and pursuing its climb undisturbed by the spattering of his tommy-gun? This intersecting of the tragic and the trivial planes of existence has always obsessed me in the Spanish Civil War, during the collapse of France, in the London blitz.

**

I am grateful to David Foster for his ChicagoBoyz post The Romance of Terrorism and War which triggered this exploration, and that on the glamour of war which will follow it.