The human voice, counterpoint, & the analysis of complex systems

Saturday, February 9th, 2019[ by Charles Cameron — with Mike Sellers and Ali Minai particularly in mind, and more to come.. ]

.

Roomful of Teeth:

That’s composer Caroline Shaw‘s Partita for 8 Voices, a piece she wrote for Roomful of Teeth.

A piece she composed and wrote for them — in the remainder of this post, we’ll explore the overlap of text (writing) and music (composition) in increasing subtlety and detail..

**

I’m brought to make this post by a paragraph I read in a fascinating New Yorker article, Roomful of Teeth Is Revolutionizing Choral Music. Roomful of Teeth is the group whose music I first praised in Pulitzer : Lamar :: Nobel : Dylan?, and showcase again in the video clip above.

Here’s that New Yorker para:

The human voice is the world’s most astonishing instrument, it’s often said. It’s capable of everything from a trill to a bark to an ear-splitting scream, from growling harmonics to liquid acrobatics, lofted on the breath like a lark on an updraft. Instrument is the wrong word, really. The voice is more like a chamber ensemble: winds and strings and blaring horns, strung together end to end. It’s a pump organ, a viola, an oboe, and the bell of a trumpet, each instrument passing the sound along to the next, adding volume and overtones at every step. Throw in the percussion of the lips and tongue, and the echoing amphitheatre of the skull, and you have a full orchestra playing inside you.

My aim in this post is to add that “full orchestra playing inside you” to that other internal polyphony of contrasting desires, identities, and emergent thoughts, and the external polyphony of all those voices with a stake in our common concerns, risk assessments and deliberations — which are constituent of our complex analytic topics.

Done.

**

The rest is context…

I’ve often talked about the notion that the analysis of complex human systems involves dealing with multiple stakeholder voices, also on occasion with the many internal voices within each individual, and suggested that music offers the clearest equivalent or analogy that humans successfully and repeatedly navigate. Specifically, the twin notions of polyphony — the sounding together of many voices — and more specifically counterpoint — the juxtaposition of conflicting voices and the possible resolution of their conflicts from dissonance to harmony in an iterative process — are clearly relevant to analytic practice, albeit drawing on a tradition that will seem wildly cross-disciplinary to many analysts.

Relevant here is Edward Said‘s definition of counterpoint:

In counterpoint a melody is always in the process of being repeated by one or another voice: the result is horizontal, rather than vertical, music. Any series of notes is thus capable of an infinite set of transformations, as the series (or melody or subject) is taken up first by one voice then by another, the voices always continuing to sound against, as well as with, all the others. Instead of the melody at the top being supported by a thicker harmonic mass beneath (as in largely vertical nineteenth century music), Bach’s contrapuntal music is regularly composed of several equal lines, sinuously interwoven, working themselves out according to stringent rules

In my view , which I have repeatedly expressed, Johann Sebastian Bach, the master of contrapuntal writing, is a significant exemplar for us at this time. And if it should be argued that musical methods cannot be transposed — another musical term — to matters of verbal thought, let me say that the great Bach pianist Glenn Gould towards the end of his life made specifically contrapuntal human voice radio plays for the Canadian Broadcasting Company..

**

Gould’s contrapuntal mind:

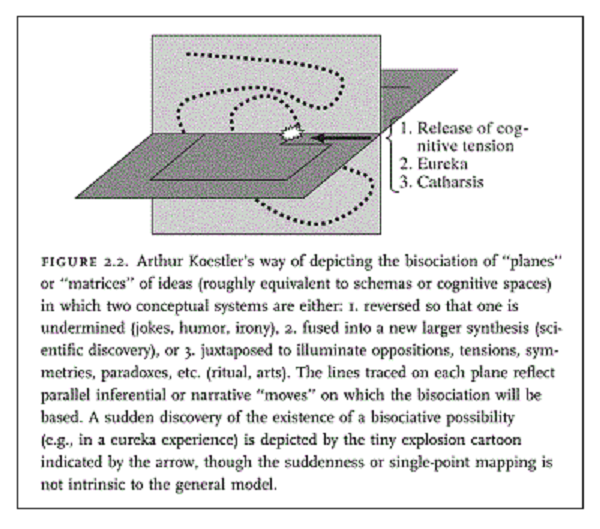

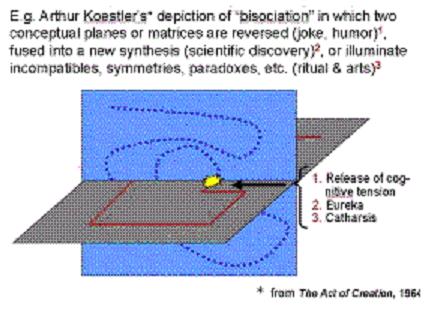

Among Gould‘s eccentricities — David Howes in Glenn Gould’s Contrapuntal Constitution calls them bi-centricities, a phrase that reminds us of Arthur Koestler‘s notion of the creative leap as the bisociation of two planes or matrices, are:

the way he liked to have one AM and one FM station playing all the time in his apartment, one for news, the other for music; the way he could learn a score while talking on the phone; and the way he enjoyed eavesdropping on three or four conversations at the same time going on at neighbouring tables in the restaurants he haunted (Kostelanetz 1983: 127).

We can see here that Gould‘s basic thinking is in terms of multiple voices, often contrasting, in simultaneous awareness — Gould, Howes continues, spoke of counterpoint as “an explosion of simultaneous ideas”. As Gould puts it, Howes reports, when speaking of his radio programs for human voices:

The basis of it was that we tried to have situations arise cogently from within the framework of the program in which the two or three voices … [recorded previously in conversation with Gould, but with the latter’s voice edited out for the final version] … could be overlapped, in which they would be heard talking – simultaneously, but from different points of view – about the same subject. We also tried to treat these voices as though they belonged to characters in a play, though all the material was gained from interviews. It was documentary material, treated in a sense as drama (cited in Payzant 1982: 131).

This, then, is Gould‘s contrapuntal radio, and we can see Gould vividly transposing conytrapuntal imagination from the musical sphere to that of the varieties of human verbalization.

**

As not an aside but the re-introduction of a theme previously only hinted at, here is Arthur Koestler on the conceptual or creative leap:

**

Okay, our concept of music must shift, change, expand, if we are to consider Gould‘s Idea of North as a musical composition — in ways that are consistent with my own development of contrapuntal analysis. As Anthony Cushing explains in Glenn Gould and ‘Opus 2’: An outline for a musical understanding of contrapuntal radio with respect to The Idea of North:

A musical understanding of North requires re-thinking some traditional elements of music theory: harmony must take into consideration semantic content and shifting topic areas; form follows somewhat traditional musical structures (ternary, binary, etc.); and texture encompasses layering of literal voices and dispenses with traditional notions of melody. One must also consider the spatial component of tape composition, in which voices inhabit locations in a sound field. The later documentaries in the trilogy and the Leopold Stokowski and Pablo Casals tribute radio documentaries contribute to a more complete musical concept of contrapuntal radio — complex polyphonic textures, stereo sound, pitch-based harmonic content — the germ of contrapuntal radio was developed and actualized in North.

I’d like to take that lead, given us by the masterful pianist Glenn Gould, across into the field of analytic understanding — as a stream of analysis complementary and in counterpoint (for instance) to “big data” analytic tools — contrapuntal analysis characteristically working with a few, humanly-selected verbal utterances rather than data-points algorithmically-selected in the millions.

**

Moving to a larger geopolitical canvas, Edward Said once told an interviewer:

When you think about it, when you think about Jew and Palestinian not separately, but as part of a symphony, there is something magnificently imposing about it. A very rich, also very tragic, also in many ways desperate history of extremes – opposites in the Hegelian sense – that is yet to receive its due. So what you are faced with is a kind of sublime grandeur of a series of tragedies, of losses, of sacrifices, of pain that would take the brain of a Bach to figure out. It would require the imagination of someone like Edmund Burke to fathom.

We see here the invocation of Bach in a context of geopolitical analysis — one paragraph in the life-work of Said, who was a music critic as well as a well-known Palestinian-American public intellectual.

That single paragraph — and Gould‘s clear understanding that contrapuntal thinking can be applied to the polyphony of human voices, not just in the musical sphere — prompts me to go further, and assert that complexity studies with application to the human condition and intelligence and geopolitical analysis will all, sooner or later, arrive at the practice of contrapuntal thinking as basic to their deeper purposes.

**

Refocusing at the national level, on Glenn Gould‘s native Canada:

I’ve mentioned the simultaneity of voices in social contexts such as listening, hearing and understanding the views and voices of multiple stakeholder. In similar vein, Howes suggests Gould‘s own taste for counterpoint stems from and reflects the Canadian Constitution:

Gould understood music to provide a model of society, and the performing artist, hence, to be performing society, as well as music. Along these lines, counterpoint, Gould’s preferred musical style, provides a specially apt model for comprehending the constitutional structure of the Canadian state. Gould’s interest in keeping the different voices of a fugue distinct, equal, and bound together parallels the concern of the Canadian state to keep the different parties to Confederation distinct, equal and bound together. In this difficult task, however, there is always a risk of overemphasizing or losing one of the voices. If Quebec is proclaimed “a distinct society” will that disturb the equality of the provinces (for surely all are distinct); if it is not, will that lead to the separation of Quebec and the break-up of Confederation? This bi-cultural counterpoint confronts Canadians daily, from the bilingual product information on their cereal boxes to the reports of English/French political jousting on the evening news.

Counterpoint, or in more general terms, polyphony, is non-dialectical, for it involves the interweaving of voices, of ideas, rather than the Hegelian process of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. Polyphony as social theory does not, therefore, entail the negation of any countervailing views the way, say, a dialectical social philosophy would. With polyphony, accommodation or peaceful co-presence takes the place of negation.

**

Readings:

New Yorker, Roomful of Teeth Is Revolutionizing Choral Music NY Times, The Glenn Gould Contrapuntal Radio Show Open Culture, Listen to Glenn Gould’s Shockingly Experimental Radio Documentary Hermitary, Glenn Gould’s The Solitude Trilogy Canadian Icon, Glenn Gould’s Contrapuntal Constitution Politics & Culture, An interview with Edward Said Charles Cameron, Pulitzer : Lamar :: Nobel : Dylan? Charles Cameron, Getting deeper into Koestler Mike Sellers, Advanced Game Design: A systems Approach Ali Minai, A core concern of our research is the desire to catch ‘creativity in the act.’

**

More Teeth — your reward for reading this far:

And Bach — Glenn Gould plays Contrapunctus IX from The Art of Fugue — on organ: