When in Rome….

Friday, July 16th, 2010

Excellent post by Dr. Bernard Finel:

The Fall of the Roman Republic: Lessons for David Petraeus and America

The problems facing the Roman Republic in the 1st Century BC were obvious for several generations before they resulted in the final crisis that lead to imperial rule. There were a large number of proposed solutions, some more fanciful than others, but it was precisely the apparent inability of the state to address problems that everyone recognized existed that destroyed the existing institutions. At the core, the Roman Republic faced two problems.

First, the growth of Roman power and the acquisition of an empire stressed the existing structure for managing provinces. The lack of a well developed colonial bureaucracy combined with the practice of annually appointing new provincial governors from the ranks of recent senior magistrates created massive instability. Significant elements of provincial administration – notably tax collection – were outsourced to private companies, and provincial governors saw their postings as an opportunity for self-enrichment, which was both a cause and consequence of the increasing cost of running for political office. The result was endemic corruption in Rome, and frequent instability in provinces as a consequence of the rapacious practices of tax farmers and governors. Particularly in the more recently acquired provinces in and around Anatolia and the Levant, this instability led to revolts and opportunities for external actors to weaken Roman control.

Second, for a variety of reasons that economic historians continue to debate, there was increasing income inequality in Rome, and worse, the gradual impoverishment and ultimately virtual elimination of small-hold farmers that had traditionally formed the backbone of both the Roman citizenry and military. The result was the rise of an urban poor, increasingly dependent on the largess of the state, more prone to violence, and ultimately more loyal to patrons than to the state as a whole. Part of this was also a consequence of empire. Military victories brought slaves to Rome, which were increasingly used to farm the large estates of aristocrats, raising land prices and lowering food costs in a way that made small farming unsustainable.

These problems were recognized early. In 133 BC, Tiberius Gracchus sought to implement land reform from his position as Tribune in order to address the twin issues of the disappearing free rural peasantry and the resultant lack of citizens eligible for military service. His efforts threatened the position of the aristocratic elites, and in the end he was murdered. Ten year later his younger brother suffered the same fate under similar circumstances. At the time of the Cimbrian War (113-101 BC), the threat of foreign invasion by Germanic tribes forced Gaius Marius to replace the traditional Roman Army soldiered by land-owning citizens with one built around landless volunteers for whom military service was a career and who owed loyalty primarily to the general paying the bills rather than the state. Marius’ legions defeated the Germans, but a new instability had been introduced into the Roman state due to the tendency of these new volunteer forces to be loyal to personal patrons rather than state institutions. This instability manifested itself in the increasing role of popular generals in Roman politics, including several willing to implicitly or explicitly threaten civil war to get what they wanted. Marius himself marched on Rome, as did Lucius Cornelius Sulla twice, and Lucius Cornelius Cinna. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) took over this father’s client army on his death and became a key power broker in his twenties and without having held elected office. By the time the of the First Triumvirate in 59BC, the Roman state had been grappling with these basic, interlocking economic, political, military challenges for 70 years without any systematic solution.

Finel sees 21st century AD America as having some analogous political and structural difficulties to 1st century BC Rome:

….The Roman system had, in short, even more veto points than the current American system, and they were even more arbitrary – though the U.S. Senate practice of anonymous holds comes close.

The point is not to suggest that Rome and the United States are in identical positions. Rather, that there are similar structural problems. In the United States today there are durable public policy problems that everyone agrees are indeed problems – deficits and debt, the entitlements crisis, lack of infrastructure investment, educational shortcomings, the erosion of U.S. manufacturing and the challenge of international competitiveness. But we can’t do anything about them because there is a rump of opposition to any structural reforms, not always from Republicans, and a large number of veto points.

Another structural similarity is that the one – or at least most – effective institution in the country is the military. In the 1st Century BC, the Romans fought at least five civil wars (as many as seven depending on how one chooses to count), and yet was able to expand their colonial empire. Their Army was occasionally bested in battles, but never in this period in a war. Over time, Roman politics came to be dominated by successful generals, and men without a martial record often sought to establish one even later in life.

It was in this context of persistent structural problems, a dysfunctional political system riddled with veto points, and a highly effective and respected military that the Roman Republic collapsed. But before it collapsed, it was given one last opportunity to save itself. This occurred with the formation of the First Triumvirate in 59 BC.

I suggest that you read Dr. Finel’s post in full.

A few comments on my part….

A commendable summarizing of the Late Republic’s dysfunction on Dr. Finel’s part. For those readers interested in the subject, I’d recommend Tom Holland’s Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic, Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar: Life of a Colossus

and Anthony Everritt’s Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician

.

A minor quibble is that Finel left out Sulla’s brutal attempt to “re-set” the political system, decrease public corruption and “restore” many older political customs by scraping away more recent innovations involving tribunican office by the fiat of breaking Roman tradition and launching a murderous purge to kill off and thoroughly terrorize those members of the senatorial elite who would object to his version of political reform. Sulla’s bloody precedent made future recourse to violence more likely after Sulla passed from the political scene. Caesar consciously used Sulla’s memory as a foil, making great political show of his generous treatment of beaten opponents, ultimately to his cost.

I would add that the rapaciousness of the tax-farming in the provinces was due in part to Roman patricians delegating that perk to Rome’s Italian Allies, making the Italians the junior partners in Roman imperialism much the same way lower and middle colonial officials and military officers of colonial armies in the British Empire in the in 17th-19th century were frequently drawn from the Scottish, Welsh and Anglo-Irish gentry and “respectable” English freeholding yeomanry. It gave these ambitious folk a stake in the system and kept the door ajar to their possible entry into the ruling class ( the Romans eventually had to yield citizenship to the Italians, though the pedigree of one’s citizenship remained an important part of a politician’s auctoritas).

I agree with Finel that Cato the Younger was a fanatical ass who more than any other figure precipitated the destruction of the Republic with his uncompromising determination to destroy Julius Caesar personally – even if he had to violate the unwritten rules of Roman politics to do so. Ironically, despite the extremism of his ulta-Optimate stance, Cato was popular with the plebians, maybe “highly respected” is a better description, because his fanaticism about adhering to Roman traditions was authentic. Moreover, unlike most politicians of the time Cato wasn’t looting everything in the provinces that wasn’t nailed down and lived an anarchronistically ascetic lifestyle for a nobleman.

Finel’s analogy of Popularii and Optimates with Republicans and Democrats works well as a narrative device for the point he is making, but it is important to keep certain differences in mind. The Optimates and Popularii were not parties in any modern sense and can’t really be equated with 21st century liberal or conservative ideology either. Roman politics was heavily personalist and based on politicians building and leveraging clientelas, rather than ideological affinities. Socially, many in the Republican base today – the rural state, conservative Christians and LMC suburbanite small businessmen – would also fit better with the Popularii and plebians.

By contrast, many (certainly not all) in the Democratic base are sociologically more like the Optimates – at least the UMC, urban-suburban technocratic professionals, academics and lawyers from “good schools” who run the Democratic Party and fill the ranks of the Obama administration. Economically, both the GOP and the Dems are, in my view, increasingly in favor of a rentier oligarchy as an American political economy, with game-rigging for corporations, tax-farming schemes to hold down and fleece the middle-class, sweetheart revolving door between government service and private contracting – all of this self-dealing behavior would be comfortably Optimate.

Could we get a “man on horseback” or a “triumvirate”? Americans have repeatedly elected generals as President, including some of Civil War vintage who were, unlike U.S. Grant, of no great distinction and Teddy Roosevelt, a mere colonel of the volunteers, was a Rough Rider all the way into the Vice-Presidency. (Incidentally, I don’t see General Petraeus or any other prominent Flag officer today being cut from the mold of Caesar, Antony or Pompey. It’s not in the American culture or military system, as a rule. The few historical exceptions to this, MacArthur, Patton and McClellan, broadcast their egomania loudly enough to prevent any Napoleonic moments from crystallizing). Never have we had an ambitious general in the Oval Office in a moment of existential crisis though – we fortunately had Lincoln and FDR then – only after the crisis has passed and they were elected them based on the reputation of successful service. It is unlikely that we would, but frustrations are high and our political class is inept and unwilling to contemplate reforming structural economic problems that might impinge upon elite interests. Instead, they use the problems as an excuse to increase their powers and reward their backers.

Being hit by another global crisis though, might predispose the public to accept drastic but quietly implemented political changes beneath the surface that leave our formal institutional conventions intact, which is how republics are lost.

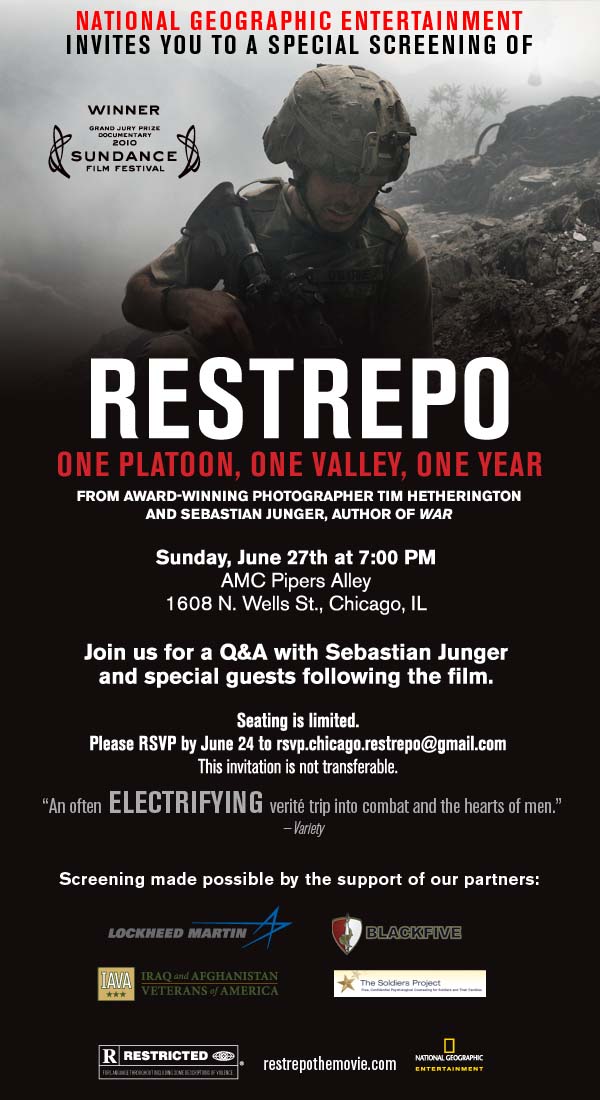

result, this book combines an analysis of the development of the insurgency based on available information with my ongoing work, focused on identifying the root causes of the weakness of the Afghan state.

result, this book combines an analysis of the development of the insurgency based on available information with my ongoing work, focused on identifying the root causes of the weakness of the Afghan state. name is pronounced with an accent on the second syllable, reh-STREP-po.

name is pronounced with an accent on the second syllable, reh-STREP-po.