Form is Insight: the project

Monday, October 22nd, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — about the (not yet titled) book (or post-book project) i seem to be writing, which offers a grand slam intro to an array of box-free contemplative and artistic approaches to creative thinking, and hence opens fresh angles on intelligence ]

.

One thing I can promise: whatever this project turns out to be, it won’t be predictable.

.This project won’t take you over familiar territory, congratulating you on holding the same opinions as the author and adding in enough choice details to keep you interested. I’m not aiming to teach you the same thing you already know, only better, more interestingly, more precisely, or in greater detail. I’m aiming to question you, challenge you, and give you a whole new range of optics through which to view the world.

**

So, here we go.

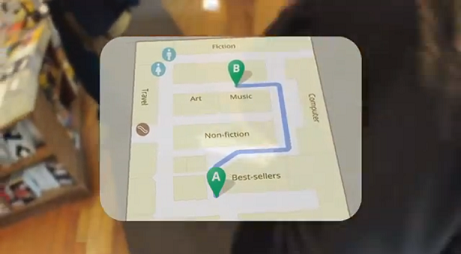

I think I am finally at the point where the book (or whatever it is) I’ve been gathering inside me all these years is ready to be written. Some of it has already emerged in earlier posts here on Zenpundit — you don’t known and couldn’t count how many thanks, Mark — and this is certainly where I’ve been developing the style of integrated visuals and verbals that gives the project its flavor — so I’d also like to use my posts here to discuss the thing with you as I go along.

The project is about intelligence in the widest sense, including heart and mind, and with particular focus on creativity. I’m addressing this from two standpoints that mesh together well, and I’m addressing it to two audiences that I believe also mesh together well.

The standpoints are (i) meditation and (ii) the arts, and the audiences are (i) the “intelligence community” and (ii) bright people in general.

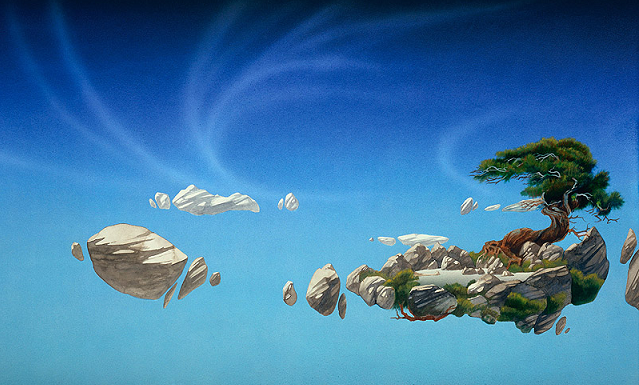

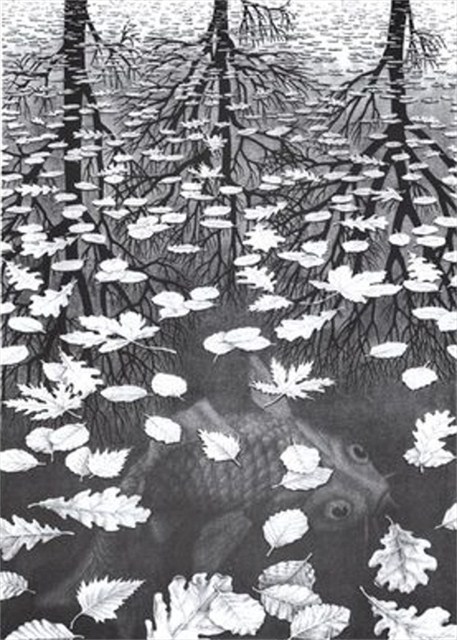

I believe that meditation cultivates a spacious mind-set in which we can hold multiple concerns in mind at the same time – the opposing needs of different people, stakeholders, sections of society, the environment, etc – thus seeing things from multiple angles and in balancing & thus balanced ways. And I think the arts serve as the primary means for expressing these balances with all their nuances and shadings, and that techniques from within the arts such as polyphony, chiaroscuro, formal constraint and pattern can teach us to shape multi-faceted insights like these into rich and complex understandings – complex patterns that respond to complex situations. I’ll go into all this in detail as we move along, with examples.

I also believe that this kind of creatively patterned insight — embodying artistic methodology in the context of complex problems with a “fresh” and open mind – will be of interest beyond the intelligence agencies and policy-makers, to business people, artists, and also — importantly — the bright general public, which I take to be a far larger subset of the population than we commonly think, and always eager for reading that doesn’t talk down to them but appreciates their own intelligence and good will.

For now let me just say that I’m very excited, because this seems (at last) to be a project that ties together my game-work with Sembl, the think-tank side of me which has been monitoring religious violence, jihad and terror and working towards nuance, understanding and peace these last dozen years — and my sense of creativity as a writer and poet.

Ripeness is all: I suspect the time for this venture has arrived.

**

Here’s the single page overview I’ve written, with a working title:

Intelligence is Zen: understanding our complex world with koans in mind

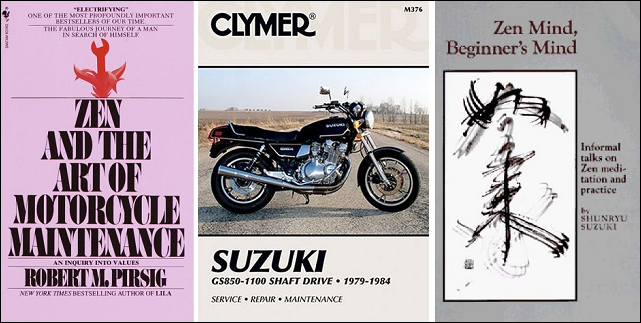

Just a few days ago, the Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, referenced Pirsig‘s book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, as key to the Intelligence Community’s work in understanding and adapting to the many, varied, intersecting problems we face in the world today. As I noted, Clapper was focused a bit more on the biker wisdom than the Zen to be found in Pirsig’s book, but he does raise a question I’ve been addressing for some years now:

What does the contemplative mind have to offer in terms of understanding a complex world?

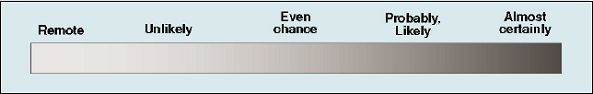

To my mind, the creativity which is all the buzz of the business world, aimed at solving what are called “wicked problems” — problems that feature multiple stakeholders with multiple aims and objectives, aims and objectives which themselves shift over time so the problems are “never the same river twice” – requires a major mental and emotional shift. Reverie and meditation free us up to make the shift: the shift itself is poorly understood.Our present, mostly linear way of thinking favors either/or side-taking, dubious cause-and-effect expectations which fail to take complex feedback loops into account, followed all too often by a rush to judgment. We need a whole new – old, even ancient – way of thinking.

Our problems are complex because they overlap, they ripple through one another. In Buddhist terms, they are “interdependently arising.” Not surprisingly, the way of thinking that is required to gain a deeper insight into “interdependently arising” problems can be found in explicit form in such contemplative traditions as Madhyamika & Zen, Taoism, Sufism, and their Abrahamic contemplative analogs. At the heart of these systems is fresh thinking – thought refreshed by quiet.

Furthermore, the shaping of insights in an open field of thought is something the world’s artistic traditions have long dealt with, and there are schools of insight not just available but recorded in exquisite detail in the world’s traditions of poetry, music, painting, theater, film… in patterns that are found in nature, in culture, and in the very turbulence we now must learn to flow with.

The project therefore takes a meditation-influenced approach to intelligence, both in the sense in which Clapper would use the word, relating to the intelligence analysis which develops and influences our decision-makers’ understanding of what’s needed, and in the more general sense of those capable folk with bright minds, keen insights, sharp instincts, warm hearts.

I’ll propose a series of ways of looking differently – with application for anyone, whether artist, intel analyst, businessman, policy-maker, or lover – that cut to the essence of creativity: lateral, analogical, holistic thinking, witnessing pattern beneath the surface of things. My examples will be mainly drawn from terrorism, which I have been monitoring for a dozen years: my style is that of a poet and an eccentric Englishman.

My subtext, my subliminal message, will be contemplation and artistry as profound common sense.