Zengi can be Zangi and Zinki, among others

Sunday, July 24th, 2016[ by Charles Cameron — besides horror at the beheading, there’s an analytic note that needs to be heard ]

.

Abdullah Issa fighting, and wounded — soon to be savagely beheaded

The ferocity of the beheading has been blurred out in most versions of the video, though ZeroCensorship is still showing it, and YouTube has a version that stops short of the beheading but appears to record Abdullah’s final wish — to be shot, not slaughtered.

That devastating final wish goes way beyond Shakespeare‘s “to be or not to be, that is the question” — it may well be the most terrfying depiction of a choice made at death-point that I have ever heard.

**

I commented recently to a post by Ehsani2 titled The Boy Beheaded by Zinki Fighters, Abdullah Tayseer, Who Was He? on Dr. Joshus Landis‘ Syria Comment blog, noting that the piece used the names Zanki and Zinki without commenting on the difference between them, and asking for clarification. I’d like to thank Dr Landis for a graciously email in response, and am happy to note today that my concern regarding the discrepant names used in the article is not without cause — as Kyle Orton just made clear in his own post on his Syrian Intifada blog, A Rebel Crime and Western Lessons in Syria:

One of the first complications with al-Zengi is the sheer variety of ways to transliterate the group’s name. Nooradeen can be Nooridin, Noorideen, and Noor/Nur al-Din/Deen; Zengi can be Zangi and Zinki, among others. Harakat means “movement,” though sometimes the organization is referred to as kataib (brigade) instead. Nooradeen refers to the twelfth-century Seljuk atabeg of the Zengid dynasty, whose life’s project was the reunification of the Islamic community.

No wonder I was confused.

**

My point, as so often, cuts against the grain of the conversation on Ehsani2’s post, which is largely about the horrible event itself and the group that performed it, one time support from the US included, and not the ways in which lack of languahger skills can cause confusion where clarity would be preferable — and that’s fair enough. My point, hiwever, is the linguistic one, and I think it’s important in a way that’s perhaps better suited to discussion here than on Dr Landis’ blog.

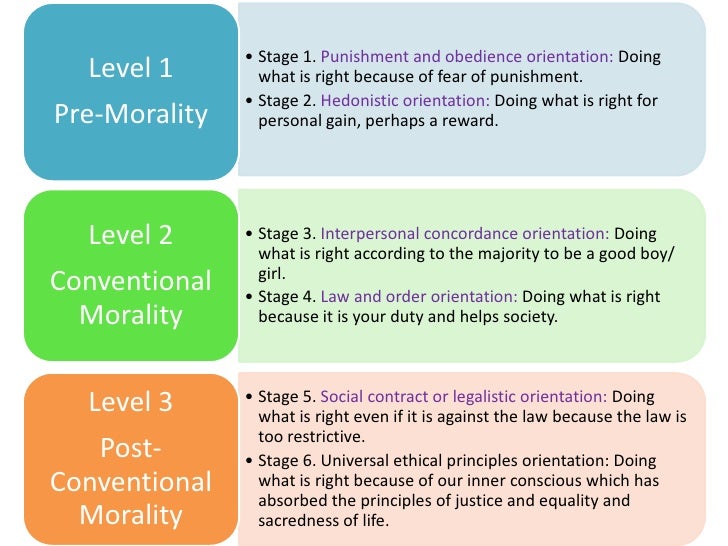

My plea is for analysts with special knowledge of places, groups or languages to bear in mind when writing, that there will be some in their interested audiences who may not share those specialities but are still worth reaching — and in particular that non-specialists, while inherently weak in local detail, may nevertheless contribute significant insights from outside linguistic or area-specialist silos, precisely by virtue of not being in the echo-chambers that such forms of specialism themselves tend to erect.

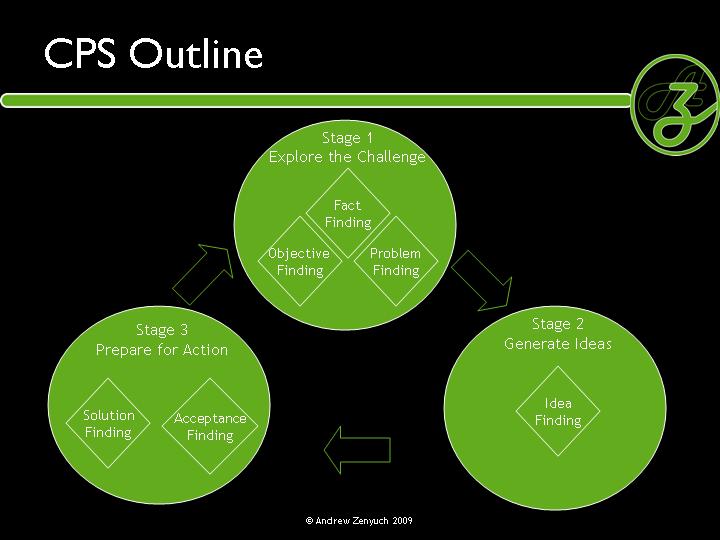

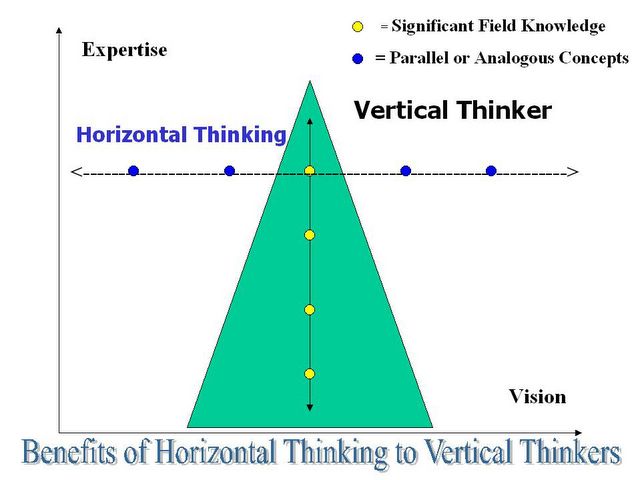

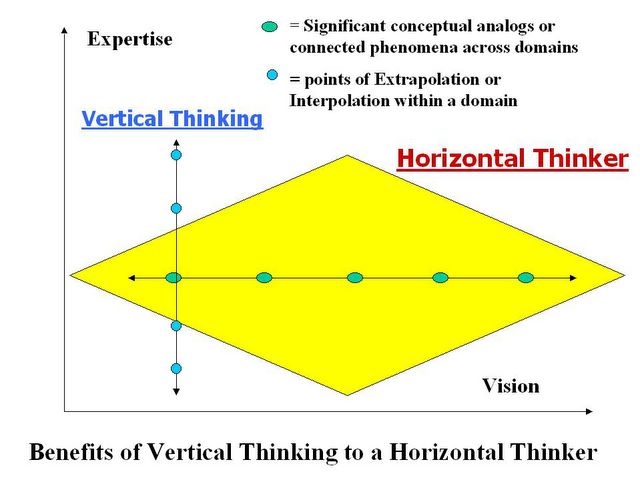

Zen has from the beginning of this blog stressed the mutual virtues of what he terms “horizontal” and “vertical” modes of knowledge — see his series:

Understanding Cognition: part I: Benefits of horizontal thinking Understanding Cognition: part II: Benefits of vertical thinking to horizontal thinkers Understanding Cognition: part III: Horizontal and vertical thinking and the origin of insight

I came to my own interest in that topic by being a primarily analogical and only secondarily linear thinker, by hearing Murray Gell-Mann at CalTech speak on the importance of generalist “bridge-makers” who perceive analogical links between otherwise unrelated disciplines, and by my twenty- to thirty-year effort to devised a playable form of the great analogical game loosely described in Hermann Hesse’s brillian (nobel-winning) novel, The Glass Bead Game.

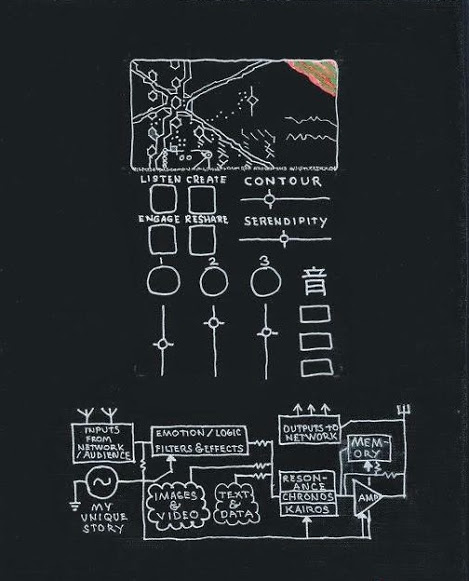

In prepping a proposal — as yet unfinished — for DARPA or IARPA last year, I formulate my basic message as a sort of motto, thus:

Out of the box, out of the silo, out of the discipline, out of the agency, out of the explicit known into the “unknowing” — where the future takes shape…

I could — and in the finished proposal will, God-willing — go far further on this topic, describing the ways in which complexity is far better modeled for us humans by analogical than by linear thinking, by cross-disciplinary than by silo’d thinking, by visual rather than verbal thinking, by human scale (7, plus or minus 2 datapoints) visualization than by big-data viz, and so forth. But let’s make it simple:

Quirky thinking has a better chance at creative insight than routine thinking, individual contrarian passion than in-group agreement.

Okay?

**

Thanks again to Dr Landis, and back to business..