One of the more interesting comments about, well..

Tuesday, October 15th, 2019[ by Charles Cameron — reading my daily dose of 3QD again after a health-induced lapse, and glad I’m back ]

.

One of the more interesting comments about, well, religion, comes from a review by Robert Fay in 3QD of Chinese science fiction master Liu Cixin‘s novel, the first in a trilogy and the one President Obama so praised, The Three Body Problem, reading it in a wide world context:

Sacrifice used to be part-and-parcel of the western self-identity. Jesus on the cross at Calvary was the central spiritual truth of Christendom. The west, of course, left much of this behind during the Enlightenment. The French Revolution further asserted the rights of individuals. If anything, the consumption of consumer goods is the true religion of the west now, and it demands we all act immediately on our impulses, cravings and desires.

This hasn’t worked out well for the planet.

**

Yes, sacrifice, and it’s dual, martyrdom, have all but disappeared, although, well, the Marines understand sacrifice, and the jihadists understand martyrdom.

To take you into the audacity of sacrifice or the self-surrender of martyrdom is beyond me here. Let me just note that the Eucharist is a sacrifice, and the death of Joan of Arc a martyrdom. Arguably, the two ideas are parallel, and meet at infinity, as in the Cure D’Ars observation:

If we knew what a Mass is, we should die of it.

Thus, theologically speaking, the Eucharist (present) cyclically repeats Christ‘s sacrifice on the cross (past), in a transcendent manner which makes of it a foretaste of the Wedding Feast (future) envisioned in the book of Revelation.

But enough!

**

There’s a fine alternative vision of the three body problem in Bill Benzon‘s Time Travelers We Are, Each And All, his account of brain, mind and Beethoven, which, like Robert Fay‘s account of Liu Cixin‘s novel of that name, arrived in today’s edition of 3QD. Benzon is quoting the literary critic Wayne Booth describing a performance of Beethoven‘s String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131 as constituting unities out of a string quartet, Booth himself and his nwife, and, somehow, both of those and Beethoven — three bodies as one:

There is Beethoven, one hundred and forty-three years ago … writing away at the marvelous theme and variations in the fourth movement. … Here is the four-players doing the best it can to make the revolutionary welding possible. And here we am, doing the best we can to turn our “self” totally into it: all of us impersonally slogging away (these tears about my son’s death? ignore them, irrelevant) to turn ourselves into that deathless quartet.

That unity of three bodies is found, and can be joined, in Beethoven‘s String Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131:

**

Reading Benzon‘s piece, we can benefit also from his presentation of neurons, their connections and internal workings:

We have no way of directly counting the neurons in the nervous systems, but estimates put the number at roughly 86 billion with an average of 10,000 synapses per neuron.

To specify the brain’s state at a given moment in clock time we need to know the state of each unit component, such as a neuron. One convenient way to do this is to say that a neuron is either firing or it is not. So it can have two states. Neurons are complicated things; each is a living cell with the full complement of machinery that that requires. There’s a lot more to a neuron that whether or not it’s firing.

This description of neurons is in service to a discussion of clock-time and brain states, which is itself in service to a wider discussion of time itself, as our wrist-watches understand it, and as our experience of Beethoven might cause us to discover it.

Following the musical branch of this discussion, we find Benzon quoting Bernstein on ego-loss:

I don’t know whether any of you have experienced that but it’s what everyone in the world is always searching for. When it happens in conducting, it happens because you identify so completely with the composer, you’ve studied him so intently, that it’s as though you’ve written the piece yourself. You completely forget who you are or where you are and you write the piece right there. You just make it up as though you never heard it before. Because you become that composer.

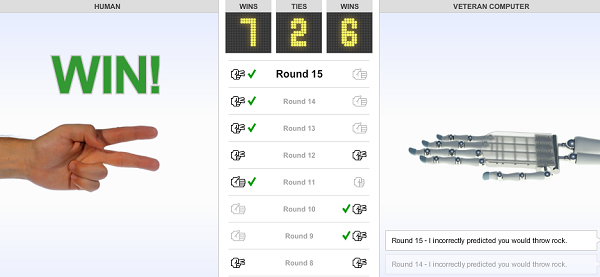

Benzon‘s three into one is Bernstein‘s two into one, and all paths lead to reliving a keynote segment of the life of Beethoven — Beethoven as a musical Everest, with Bernstein and the quartet as sherpas, Booth and his wife and Benzon and you and I as climbers, some at base-camp listening to the great Chuck Berry, some on the final ascent, some planting flags at the peak..

Peak Beethoven is phenomenological unity. Across time, time travel.

**

Oh, the numbers games one can play — Sixteen into forty into one in Tallis’ forty-part motet, Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui — where the very title speaks to the union – I Have Hope in None Other:

Oh and is not religion at the heart of this unity, this unity at the very heart of religion? And is not this braiding of voices, this polyphony, a working of this unity?

**

My early mentor and friend, Herbert Warner Allen, wrote of his own time with Beethoven. As I wrote elsewhere:

Herbert Warner Allen, a classical scholar, sometime newspaper editor and noted authority on wines, experienced a timeless moment between two beats during a performance of one of the Beethoven symphonies. Not knowing quite what had hit him, he went on to research the mystical tradition and wrote three mostly forgotten books [of which the first was aptly named The Timeless Moment] situating his experience within intellectual tradition without nailing it to any particular dogmatic structure. TS Eliot, who published the books, inscribed a book of his own poetry to Warner Allen with the words “from the Srotaapanna to the Arhat, TS Eliot”, with a footnote to explain “Srotaapanna: he who has dipped one toe in the river of the wqaters of enlightenment; Arhat: he who has arrived at the further shore”.

Here’s the almost anonymous A.T. writing to The Times, 19th January 1968:

In your obituary notice of the late Mr. Warner Allen you do not mention the books he wrote describing his “journey on the Mystic Way”. The best known of these books was The Timeless Moment in which he gave some account of a visionary experience that for him “flashed up lightning-wise during a performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony at the Queen’s Hall “. In this split second of time he received (as no one reading his books can doubt) a flash of absolute reality that broke through the normal barriers of the conscious mind and left a trail of illumination in its wake. Mr. Allen never claimed to be an advanced mystic or profound philosopher. He described himself as an ordinary man of the world. He spent years unravelling the implications of his strange experience. The resulting volumes were and are of extraordinary interest.

Amen. Warner Allen’s was a Timeless Moment, an ego-loss indeed!

I must have been fifteen or so when I had the great good fortune to meet and be befriended by this extraordinary man..