[ by Charles Cameron — on self representation, avatars, and what we may be missing ]

.

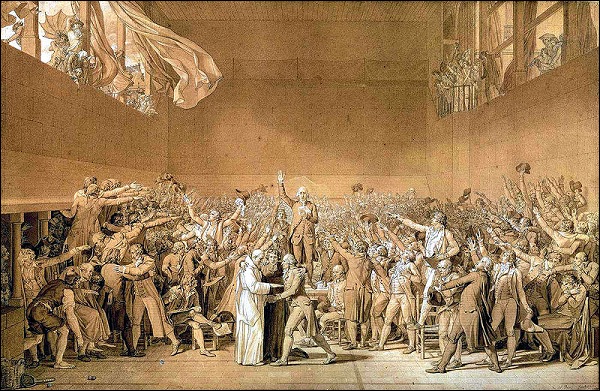

Caravaggio, Martha and Mary Magdalen, aka The Conversion of the Magdalen

**

Where to begin?

The Washington Post doesn’t like selfies much, according to Galen Guengerich in the Religion, yes, the Religion section — in a post titled ‘Selfie’ culture promotes a degraded worldview he writes:

The 2013 word of the year, according to the Oxford Dictionaries, was “selfie,” which Oxford defines as “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” The first use of the term, according to Oxford, occurred when a young Australian got drunk at a friend’s 21st birthday party and fell down the stairs. He hit lip-first and his front teeth punched a hole in his bottom lip. His response was to take a photo of himself and post it online for his friends to see. “Sorry about the focus,” he wrote, “It was a selfie.”

Okayyyyy…

As usual, the Kierkegaard / Kardashian combo that tweets as @KimKierkegaard manages to straddle the worlds material (in the Madonna sense) and spiritual (in the sense of the Madonna):

**

I wanted to dig deeper — the WashPost Religion section, Kierkegaard, how could I not? I often want to dig deeper, and today I was driven to do so because today — not or the first time — I ran across a terrorism analyst and blogger named Cristina Caravaggio Giancchini, who uses a detail from her namesake Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio‘s Martha and Mary Magdalen (above) as her avatar…

Avatars are a kind of selfie, aren’t they?

In any case, I found myself looking for the particular Caravaggio that contains that detail, discovering it was the Martha and Mary Magdalen, which you see that the top of this post — then kept on digging via Google to learn a little more.

**

Here’s what I found in a blog post titled Fingers and Mirrors: Caravaggio and the Conversion of Mary Magdalene in Renaissance Rome:

The inclusion of the mirror asks viewers to enter into a dynamic conversation about their own delight in the rich textures of the picture; alongside a powder puff and comb, it points us to Mary’s vanity, and her concern with the things of this world. Rather than showing Mary to herself, however, the mirror captures a diamond of light — a visual representation of the divine grace that inspires Mary to look beyond her earthly passions. The flower that Mary clutches to her chest is an orange blossom: symbol of purity.

As Debora Shuger realises, in a stimulating essay on early modern mirrors, for Renaissance viewers ‘the object viewed in the mirror is almost never the self’ (22). Such mirrors are, Shuger suggests, if not totally Platonic (reflected an absolute ideal), at least ‘platonically angled, titled upwards in order to reflect paradigms rather than the perceiving eye’ (26). Renaissance mirrors, she concludes, ask us to think differently about the mental worlds and self-awareness of people living in this period: ‘they reflect a selfhood that … is beheld, and beholds itself, in relation to God’ (38).

Pilgrims who travelled to Aachen in the fifteenth-century appear to have purchased small convex mirrors as souvenirs: as relics were carried through the thronging crowds, travellers held up the mirrors to catch a glimpse of them, and then preserved the mirrors as objects which, according to Rayna Kalas, ‘betokened that moment when the pilgrim had a vision of and was visible before the sacred relic. … Every subsequent glance at this mirror memento might serve to remind the believer of that glimpse of sacred divinity’. In Caravaggio’s painting, though, Mary looks away from the mirror which might capture her reflection (the ‘dark glass’ of Corinthians?), and towards her shadowed but persuasive sister.

**

We began this post with the idea that our 21st century ‘Selfie’ culture “promotes a degraded worldview” — and here by way of contrast, in the use of hand-held mirrors in 15th century Aachen, we see what we are missing…

… a glimpse of the sacred, in which the sacred glimpses us in transcendent return.