Book Review: Paul Cartledge’s Alexander the Great

Sunday, April 19th, 2009

” …he was one of the most extraordinary individuals to have ever walked the earth. He above all others deserves to be called, “the Great’.”

Alexander the Great by Paul Cartledge

Cambridge classicist Paul Cartledge has the rarest of talents among professional historians – the ability to write books that simultaneously appeal to academics and popular audiences alike. Alexander the Great has his trademark “concise depth” that Cartledge also brought to bear in The Spartans and later to Thermopylae: The Battle That Changed the World

; there is enough historiographic “meat” for the scholar and the casual student of history or of war will enjoy Cartledge’s depiction of Alexander as a “ruthless pragmatist”, engaging in calculated gestures of epic magnaminity and brutal murder of his closest comrades in arms with equal certitude. One who, despite his mysticism and growing tyranny, had imperial ambitions that “….can symbolize peaceful, multi-ethnic coexistence”.

Cartledge, despite the above quotation, is not an Alexander-worshipper but a realist or a mild skeptic, rejecting hyperbole and hidden

“Alexander’s importation and integration of oriental troops into the Macedonian army was a crucial and controversial issue. by the end of 328 he had units of Sogdian and bactrian cavalry, so presumably he was drawing also upon the excellent cavalry of western and central Iran. In 327 he recruited more than thirty thousand young Iranians. Since Greek was to be the lingua franca of the new Empire, replacing the use of the Achaemenids use of Aramaic, he arranged for them to be taught the Greek language as well as the demonstrably supeior Macedonian infantry tactics. when they arrived at Susa in 324, he hailed them as ‘ successors’ – to the Macedonian soldiers understandable consternation” [ 204 ]

Cartledge discusses Alexander’s generalship and his abilities as an adaptive military innovator, building on a his father Philip’s original military reforms or improvising when faced with unexpected difficulties at river crossing or in siege warfare. He misses though an opportunity to explain the dreadful effectiveness in Alexander’s hands of the Macedonian phalanx, a more heavily armed, lightly armored, mobile and deadly version of the original Greek Hoplite formation. While Alexander and his cavalry garnered most of the glory, the ordinary Macedonian phalanx cut through Persian ranks like an implacable meat grinder, mowing down enormous numbers of the enemy and trodding their dead and dying bodies underfoot. Understandably though, this is a biography of Alexander and not a history of his wars but the real scale of the slaughter Alexander inflicted is given far less attention than the skill with which he inflicted it, or his political and religious policies that came in their wake.

Alexander’s religious sentiments and his mysticism, which spilled over in to his political vision for Asia and for himself as a semi-divine ruler are given much consideration by Cartledge, ranging from his at a distance dealings with subject state Athens, to his “contracting” a relationship with the Egyptian god Ammon, to his ideation with Achilles as a model for himself. There appears to have been something of a feedback loop between Alexander’s military acheivments, which were truly superhuman, and his growing religious superstitions, both of which fed a kind of megalomania according to Cartledge, and led to Alexander’s unsuccessful demand that his Greek and Macedonian soldiers adopt proskynesis in the Persian style. A more or less blasphemous act of hubris ( though not quite absolutely, as Cartledge explains, given the precedent of the deification of Lysander) that led to a break between Alexander and his most loyal followers. This craving for divinity later was expanded posthumously to fabulous extremes in the traditions of the Alexander Romance, where Alexander the Great becomes a symbolic and heavily mythologized figure for dozens of peoples and regimes. Alexander himself began cultivating the myths.

Cartledge has done an excellent job demystifying one of the archetypal figures of Western history, the man whom other would-be world conquerors had to measure themselves against – reportedly, Julius Caesar wept in despair because Alexander’s glory was beyond his reach. He has also brought out the extent to which Alexander saw himself not as a Westerner, or a Hellene, but as a bridge to the East, a synthesizer of civilizations.

has a more general implication:

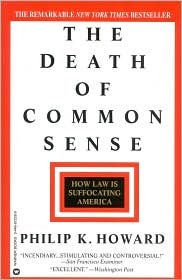

has a more general implication: Suffocating America

Suffocating America