[ Charles Cameron presenting guest-blogger Timothy Furnish ]

.

.

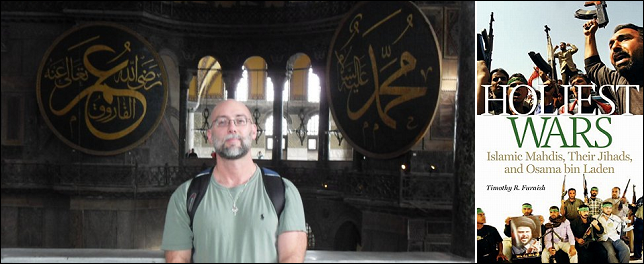

I’m delighted to welcome Dr Timothy Furnish as a guest-blogger here on Zenpundit. Dr Furnish has served as an Arabic linguist with the 101st Airborne and as an Army chaplain, holds a PhD in Islamic history from Ohio State, is the author of Holiest Wars: Islamic Mahdis, Their Jihads, and Osama bin Laden (2005), and blogs at MahdiWatch. His extended piece for the History News Network, The Ideology Behind the Boston Marathon Bombing, recently received “top billing” in Zen’s Recommended Reading of April 24th.

**

Does This Paint It Black, or Am I A Fool to Cry? Breaking Down the New Pew Study of Muslims

by Timothy R. Furnish, PhD

.

Pew has released another massive installment of data from its research, 2008-2012, into Muslim attitudes, entitled “The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society.” Over 38,000 Muslims in almost 40 countries were surveyed, thus constituting a survey both statistically sound and geographically expansive. Herewith is an analysis of that information and what seem to be its major ramifications.

The first section deals with shari`a, usually rendered simply as “Islamic law” but more accurately defined as “the rules of correct practice” which “cover every possible human contingency, social and individual, from birth to death” and based upon the Qur’an and hadiths (sayings and practices attributed to Muhammad) as interpreted by Islamic religious scholars (Marshal G.S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, Vol 1: The Classical Age of Islam, p. 74). Asked “should sharia [as Pew anglicizes it] be the law of the land,” 57% of Muslims across 38 countries answered “yes” — including, most problematically for the US: 99% of Afghans, 91% of Iraqis, 89% of Palestinians, 84% of Pakistanis and even 74% of Egyptians. Should sharia apply to non-Muslims as well as Muslims? Across 21 countries surveyed on this question, 40% answered affirmatively — with the highest positive response coming from Egypt (its 74% exceeding even Afghanistan’s 61%). And on the question whether sharia punishments — such as whippings and cutting off of thieves’ hands — should be enacted, the 20-country average was 52%, led by Pakistan (88%), Afghanistan (81%), the Palestinian Territories [PT] (76%) and Egypt (70-%). On the specific penalty of stoning for adultery, the 20-country average was 51% — with, again, Pakistan (89%), Afghanistan (85%), the PT (84%) and Egypt (71%) highest in approval. Finally, 38% of Muslims, across those same 20 nations, support the death penalty for those leaving Islam for another religion.

Huge majorities of Muslims across most of these surveyed nations say that “it’s good others can practice their faith” — but Pew’s imprecise terminology on this topic makes possible that this simply mean many Muslims are willing to grant non-Muslims the tolerated, but second-class, ancient status of the dhimmi. Majorities, too, in most countries say that “democracy is better than a powerful leader;” however, the latter was actually preferred by most surveyed in Russia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as by 42% of Iraqis, 40% of Palestinians and 36% of Egyptians. Most Afghans, Egyptians and Tunisians (and even 1/3 of Turks) believe that “Islamic political parties” are better than other ones, although 53% of Indonesians and 45% of Iraqis are also worried about “Muslim extremists.” (Curiously, 31% of Malaysians are, on the other hand, worried about “Christian extremists” — although evidence of such existing in that country is practically non-existent.) There is good news on the question of suicide bombing, however: across 20 countries, only 13.5% think it is ever justified — although the support is much higher in the PT (40%), Afghanistan (39%) and Egypt (29%).

In terms of morality, large majorities in most Muslim countries (especially outside Sub-Saharan Africa) think drinking alcohol is morally repugnant, notably in Malaysia (93%), Pakistan and Indonesia (both 91%). Most Muslims in most countries surveyed consider abortion wrong, as well as pre- and extra-marital sex and, almost needless to say, homosexuality. (Although one wishes Pew had asked about mu`tah, or “temporary marriage” — a practice originally Twelver Shi`i which has increasingly become used by Sunnis.) Yet, simultaneously — following Qur’anic rubrics — some 30% of Muslims in 21 countries support polygamy, including almost half of Palestinians, 46% of Iraqis and 41% of Egyptians. There is also significant support for honor killings in not just Afghanistan and Iraq but also Egypt and the PT. Over ¾ of Muslims across 23 countries says that “wives must always obey their husbands:” an average of 77%. And Pew notes that there is a statistically very significant correlation between sharia-support and believing women have few(er) rights.

Asked whether they believed they were “following Muhammad’s example,” 75% of Afghans and 55% of Iraqis answered affirmatively — although most Muslims were not nearly so confident. On the question “are Sunni-Shi`i tensions a problem,” 38% of Lebanese, 34% of Pakistanis, 23% of Iraqis and 20% of Afghans said “yes.”

It is no surprise that huge majorities of Muslims in most surveyed countries believe that Islam is the only path to salvation, nor that most also say “it’s a duty to convert others” to Islam. It is somewhat counterintuitive, however, that many Muslims say they “know little about Christianity” — even in places with large Christian minorities, such as Egypt. Muslims in Sub-Saharan Africa are the most likely to agree that “Islam and Christianity have a lot in common,” and so are 42% of Palestianians, as well as some 1/3 of Lebanese and Egyptians. But only 10% of Pakistanis agree. Asked whether they ever engaged in “interfaith meetings,” many Muslims in Sub-Saharan Africa said that they did (with Christians), and a majority of Thais said likewise (albeit with Buddhists). But only 8% of Palestinians, 5% of Iraqis, and 4% of Egyptians said they ever do so—despite substantial Christian populations in each of those areas.

Regarding the question “are religion and science in conflict,” most Muslims said “no” — with the exceptions of Lebanon, Bangladesh, Tunisia and Turkey where over 40% in each country (and, actually, a majority in Lebanon) said that they were at loggerheads. Most Muslims also say they have no problems with believing in Allah and evolution — the exceptions being the majority of Afghans and Indonesians. Regarding popular culture, clear majorities of Muslims in many countries say they like Western music, TV and movies—but, at the same time, similar majorities say that such things undermine morality (although Bollywood less so than Hollywood).

Observations:

1) The high degree of support for sharia is the red flag here. Contra media and adminstration (both Obama and Bush) assurances that most Muslims are “moderate,” empirical data now exists that clearly shows most Muslims, in point of fact, support not just sharia in general but its brutal punishments. Perhaps just as disturbing, almost four in ten Muslims are in favor of killing those who choose to follow another religion. And countries in which the US is heavily involved either diplomatically or militarily (or both) are the very ones where such sentiments run most high: Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, the Palestinian Territories. So are the “extremists” these very Muslims who want to follow, literally, the Qur’an and hadiths? Messers Brennan, Holder and Obama have some explaining to do.

2) Afghanistan would appear to be a lost cause. Afghans are at the top of almost every list in support for not just sharia, suicide bombing, honor killing and — ironically (or perhaps not) — confidence that they are emulating Islam’s founder, as well as dislike for democracy. In light of this clear data, two points about Afghanistan become clear: tactically, ostensible American befuddlement as to the causes of “green on blue” attacks and the continuing popularity of the Taliban in Afghanistan appears as willful ignorance; strategically, the US decision to stay there after taking out the al-Qa`ida [AQ] staging, post-9/11, and attempt to modernize Afghanistan was a huge, neo-Wilsonian mistake. 2014 cannot come soon enough.

3) In some ways Islam in Southeastern Europe, and to a lesser extent in Central Asia, seems to be a more tolerant brand of the faith than the Middle Eastern variety. For example, the SE European and Central Asian Muslims are the least likely to support the death penalty for “apostasy,” and the most supportive of letting women decide for themselves whether to veil. And Muslims in Sub-Saharan Africa are the most likely to know about Christianity, and to interact with Christians. On the other hand, African Muslims are among the most enamored of sharia, and Central Asian ones fond of letting qadis (Islamic judges) decide family and property disputes. So there does not seem to be a direct link between Westernization and moderation; in fact, the influence of Sufism — Islamic mysticism — in the regard needs to be correlated and studied (beyond what Pew did on the topic in last year’s analysis).

4) One bit of prognostication based on this data: Malaysia may be the next breeding ground of Islamic terrorism. It’s home to some 17 million Muslims (61% of its 28 million people), who hold a congeries of unsettling views: 86% want sharia the law of the land; 67% favor the death penalty for apostasy; 66% like sharia-compliant corporal punishments; 60% support stoning for adultery; and 18% think suicide bombing is justified. PACOM, SOCOM and the intelligence agencies need to ramp up hiring of Malay linguists and analysts.

5) Finally, some words for those — like FNC’s Megyn Kelly and Julie Roginsky (on the former’s show “American Live,” 4/30/13) — who pose a sociopolitical and moral equivalence between Muslim support for sharia and Evangelical Protestant Christian support for wives’ obedience to husbands: that’s a bit too much sympathy for the devil. Yes, Evangelical Christian pastors hold some pretty conservative views of the family, as per a 2011 Pew study of them; for example, 55% of them do agree that “a wife must always obey her husband” (compared to 77% of Muslims). And, ironically, many such Evangelicals agree in large measure with Muslims on issues such as the immorality of alcohol, abortion and homosexuality. However, one searches in vain for any Evangelical (or other) Christian support for whippings, stonings, amputation of thieves’ limbs, polygamy or suicide bombing.

Islam is the world’s second-largest religion, numbering some 1.6 billion humans (behind only Christianity’s 2.2 billion). There is, thus, enormous diversity of opinion on many issues of doctrine and practice, and essentializing Islam as either “peaceful” or “violent” is fraught with peril. Nonetheless, this latest Pew study provides empirical evidence that many — far too many — Muslims cling to a literalist, supremacist and indeed brutal view of their religion. Insha’allah, this will change eventually — but time is not necessarily on our side.