Of children, cultural differences, and computers

Saturday, December 15th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — kids, computers, creativity and games ]

.

It’s quite a triumphant story, with African kids in the foreground and Nicholas Negroponte and MIT playing the role of proud parents pushing them forward from behind…

With 100 million first-grade-aged children worldwide having no access to schooling, the One Laptop Per Child organization is trying something new in two remote Ethiopian villages—simply dropping off tablet computers with preloaded programs and seeing what happens. The goal: to see if illiterate kids with no previous exposure to written words can learn how to read all by themselves, by experimenting with the tablet and its preloaded alphabet-training games, e-books, movies, cartoons, paintings, and other programs. Early observations are encouraging, said Nicholas Negroponte, OLPC’s founder, at MIT Technology Review’s EmTech conference last week.

[ … ]

Earlier this year, OLPC workers dropped off closed boxes containing the tablets, taped shut, with no instruction. “I thought the kids would play with the boxes. Within four minutes, one kid not only opened the box, found the on-off switch … powered it up. Within five days, they were using 47 apps per child, per day. Within two weeks, they were singing ABC songs in the village, and within five months, they had hacked Android,” Negroponte said. “Some idiot in our organization or in the Media Lab had disabled the camera, and they figured out the camera, and had hacked Android.”

That’s a striking story, and it has caught many people’s attention since David Talbot wrote about it in a piece in MIT’s Technology Review in late October, titled Given Tablets but No Teachers, Ethiopian Children Teach Themselves.

**

I’d like to let that sink in — because I don’t want to deny it, in fact I want to share the excitement — but I do, too, want to juxtapose it with something else I read recently, where we’ll see some other African children, and where a different set of questions about their intelligence are in the air.

This quote is from Malcolm Gladwell, in a New Yorker piece titled None of the Above: what IQ can’t tell you about race:

The psychologist Michael Cole and some colleagues once gave members of the Kpelle tribe, in Liberia, a version of the WISC similarities test: they took a basket of food, tools, containers, and clothing and asked the tribesmen to sort them into appropriate categories. To the frustration of the researchers, the Kpelle chose functional pairings. They put a potato and a knife together because a knife is used to cut a potato. “A wise man could only do such-and-such,” they explained. Finally, the researchers asked, “How would a fool do it?” The tribesmen immediately re-sorted the items into the “right” categories. It can be argued that taxonomical categories are a developmental improvement— — that is, that the Kpelle would be more likely to advance, technologically and scientifically, if they started to see the world that way. But to label them less intelligent than Westerners, on the basis of their performance on that test, is merely to state that they have different cognitive preferences and habits. And if I.Q. varies with habits of mind, which can be adopted or discarded in a generation, what, exactly, is all the fuss about?

That one, of course, concerns me deeply — in fact they both do.

**

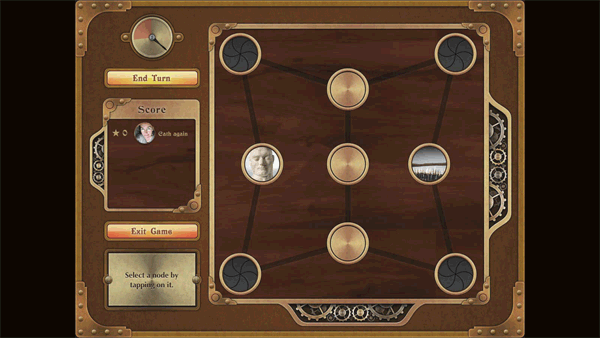

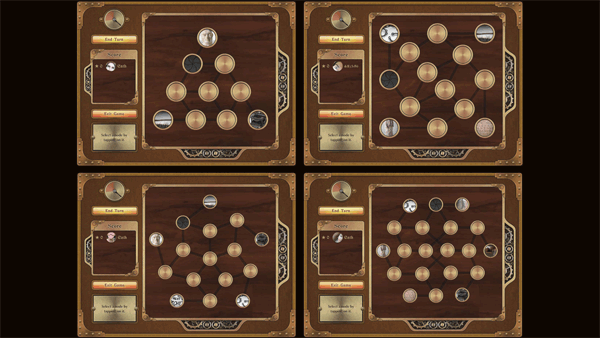

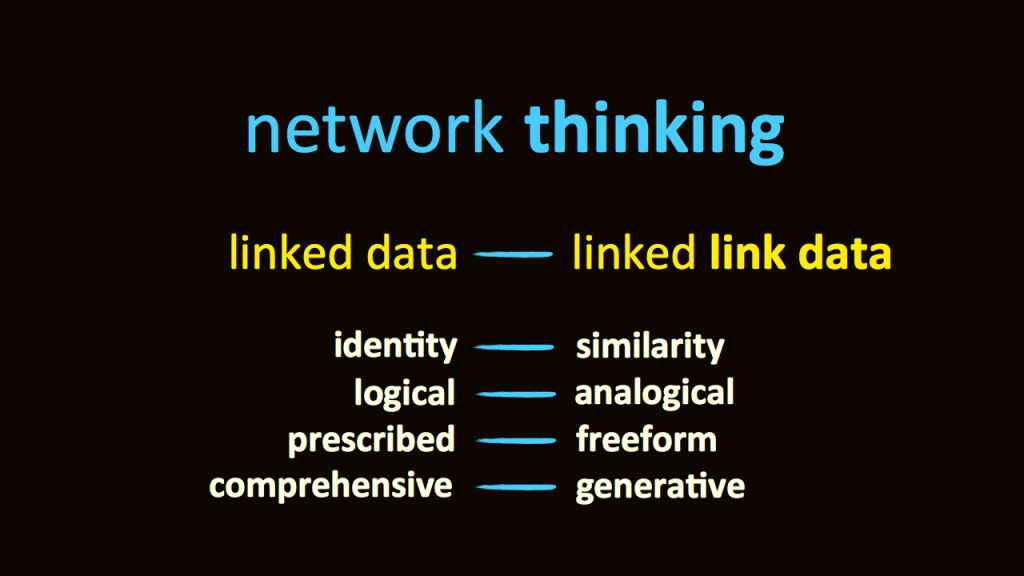

Look, my work with Cath Styles on the Sembl Game is predicated on the importance of resemblances — so the more cognitive preferences we can marshal by inviting people to make rich and varied links between things — Kpelle-style, western-style, art-style, science-style, you think of it, you name it — the better. But clearly we should also be aware in using and propagating the game that different styles of association exist, and should be explored.

And the first quote? That’s important too, because it shows the eagerness to learn that’s there, innate, before our culturally-acquired habits and assumptions and behaviors inhibit the childlike excitement of discovery, recognition, eureka! and aha!

**

Howard Rheingold once said of community-building digital media such as this blog, “Like all technologies, this medium has its shadow side, and there are ways to abuse it.”

When feeling the thrill of “up” stories like Negroponte’s, it may we wise to ask also what the “down” side might be. And IMO, there’s always room for optimism — but let’s keep it cautious, eh?