A triptych for Jane McGonigal

Thursday, October 18th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — on play, games, vertigo and koan — technically this is a ludibrium, a jeu, a jest — a dervish whirl for the mind ]

.

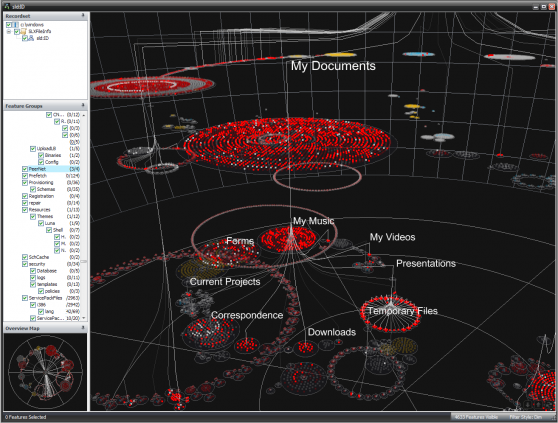

I’m joining the conversation Jane McGonigal is leading over on Big Questions Online — our topic is How Might Video Games Be Good for Us? — and she came up with a gem of a quote from Huizinga‘s Homo Ludens which pointed me to two other quotes that are part of the collection I keep in mind, one from Wittgenstein, the other from Roger Caillois.

**

I’ve strung them together here because the way the mind hops and skips from one idea to the next in this series enchants me:

There’s more to those three quotes taken together, along with the leaps between them, than there is in keeping them apart. They have, what was it Wittgenstein said? — a family resemblance. They belong together. You could start with the third quote, in fact, and then hop to the first and second, and the effect would be much the same, you could make a ring of them.

**

They spiral so closely in on one another, indeed, as to induce ilynx, vertigo. Let’s keep on spinning.

To my mind, the master of vertigo in our times is Jorge Luis Borges, who uses the word “vertiginous” at least four times in his fictions — my favorite arriving in his story The Circular Ruins, where he writes:

He understood that modeling the incoherent and vertiginous matter of which dreams are composed was the most difficult task that a man could undertake, even though he should penetrate all the enigmas of a superior and inferior order; much more difficult than weaving a rope out of sand or coining the faceless wind.

Blam! — is there anything more vertiginous than paradox, enigma, koan, mystery?

**

In perspective, there’s the vanishing point. In service to others, there’s forgetfulness of self.

**

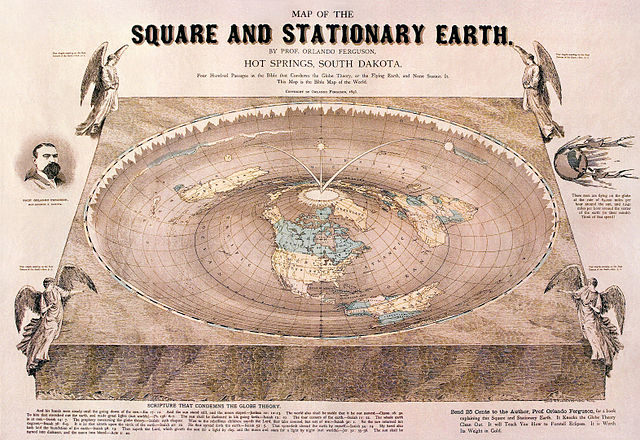

While we’re on the subject of play, I have a confession to make. Several times on this blog and elsewhere, I have cited the art historian Edgar Wind as saying that Ficino’s motto was “studiossime ludere” and that he translated it “play most assiduously” — Marsilio Ficino being the intellectual hub of Renaissance Florence under the Medici. When I was putting together my initial post to Jane McGonigal for her Big Questions discussion, I wanted to use that quote, but couldn’t quite find it in the source I thought it came from. Well, I’ve been doing some checking since then, and Wind does quote something very similar in his Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance — but the phrase is “studiosissime ludere”, and what he writes is this —

Serio ludere was a Socratic maxim of Cusanus, Ficino, Pico, Calcagnini — not to mention Bocchi, who introduced the very phrase into the title of his Symbolicae quaestiones: ‘quas serio ludebat’.[1]

which he then footnotes thus (translation coming up shortly):

[1.] cf. Ficino, In parmeniden (Prooemium), Opera, p. 1137: ‘Pythagorae, Socratisque et Platonis mos erat, ubique divina mysteria figuris involucrisque obtegere, … iocari serio, et studiosissime ludere.’

Then there’s Ioan Couliano, another great scholar of Renaisssance thought — and a victim of Ceausescu‘s secret police — in Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, translates for us (pp. 37-38):

Pseudo-Egyptian hieroglyphics, emblems and impresae were wonderfully suited to the playful spirit of Florentine Platonism, to the mysterious and “mystifying” quality Ficino believed it had. “Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato had the habit of hiding all divine mysteries behind the veil of figurative language to protect their wisdom modestly from the Sophist’s boastfulness, of joking seriously and playing assiduously, iocari serio et studiosissime ludere.” [34] That famous turn of phrase of Ficino’s — translation of a remark by Xenophon concerning the Socratic method — depicts, at bottom, the quintessence of every phantasmic process, whether it be Eros, the Art of Memory, magic, or alchemy — the ludus puerorum, preeminently a game for children. What, indeed, are we doing in any of the above if not playing with phantasms, trying to keep up with their game, which the benevolent unconscious sets up for us? Now, it is not easy to play a game whose rules are not known ahead of time. We must apply ourselves seriously, assiduously, to try and understand and learn them so that the disclosures made to us may not remain unanswered by us.

Couliano footnotes the quote thus:

[34.] Proem. in Platonis Parmenidem (Opera, II, p. 1137). This is simply the Latin translation of an expression Xenophon had used to designate the Socratic method (paizein spoude). On the custom of the “serious games” of Ficino and his contemporaries, see Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance 3d ed. (Oxford, 1980), pp. 236-38.

**

Okay, I was trying to check a Latin tag that I’d obviously been quoting from memory, and things just kept on spinning — and weaving — together.

So where are we now? We’re talking of “playing with phantasms, trying to keep up with their game” (Couliano) — and thus back at that Borges quote, too, with its “incoherent and vertiginous matter of which dreams are composed”…

Which is us.

I mean, “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”

**

Okay. Practical matters. To go along with Witty Wittgenstein and the others on my recommended reading list, here’s an image of McGonigal’s dissertation and book:

The dissertation is available here as a .pdf: the book is available here on Amazon.