Big Pharaoh: Levels of complexity in presentation

Thursday, August 29th, 2013[ by Charles Cameron — Syria, yes, but with a focus on networks, tensions, mapping, and understanding ]

.

Binary logic is a poor basis for foreign policy, as Tukhachevskii said on Small Wars Council’s Syria under Bashir Assad: crumbling now? thread, pointing us to the work of The Big Pharaoh. Here are two of the Big Pharaoh’s recent (before Obama‘s “undecided” speech) tweets:

US will bomb a mass murderer and indirectly help a cannibal. #strangedays

— The Big Pharaoh (@TheBigPharaoh) August 27, 2013

Al Qaeda jihadists will cry Allahu Akbar when US cruise missiles fall on Assad. #strangedays

— The Big Pharaoh (@TheBigPharaoh) August 27, 2013

Each of those tweets is non-linear in its own way, but via its implications — we “complete the loop” by knowing that the “mass murderer” is the Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad and the “cannibal” is the Syrian rebel, Abu Sakkar, and that Al-Qaeda typically cries “allahu Akbar” after killing Americans, while Americans typically rejoice after killing Al-Qaeda operatives. So these two tweets are already non-linear, but not as complex as what comes next>

**

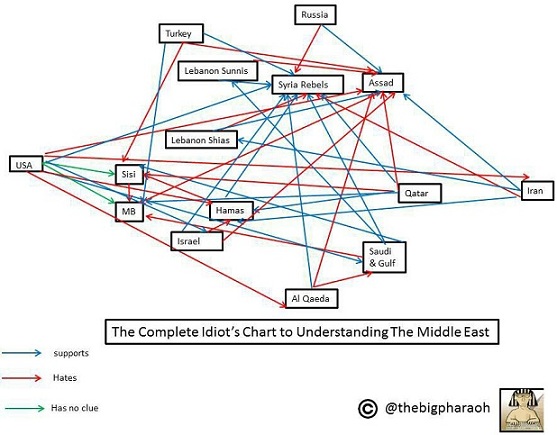

The Big Pharaoh also put this diagram on his blog, and Max Fisher picked it up and blogged it at the Washington Post as The Middle East, explained in one (sort of terrifying) chart:

I’d have some questions here, of course — one about the directionality of the arrows, which only seem to go in one direction — okay for the “supports” and “has nu clue” arrows, perhaps, but surely the “haters” would mostly be two-way, with AQ hating US as well as US hating AQ? There’s no mention of Jordan, I might ask about that… And there are no arrows at all between Lebanese Shias and Lebanese Sunnis — hunh?

**

What really intrigues me here, though, is that while this chart with fifteen “nodes” or players captures many more “edges” or connections between them than either or even both of the two tweets above, the tweets evoke a more richly human “feel” for the connections they reference, by drawing on human memories of the various parties and their actions.

Thus on the face of it, the diagram is the more complex representation, but when taken into human perception and understanding, the tweets offer a more immediuate and visceral sense of their respective situations.

And scaled down and in broad strokes, that’s the difference between “big data” analytic tools on the one hand, and HipBone-Sembl approach to mapping on the other. A HipBone-Sembl board may offer you two, or six, ten, maybe even a dozen nodes, but it fills them with rich anecdotal associations, both intellectual and emotional — a very different approach from — and one that I feel is complementary to — a big data search for a needle in a global needlestack…

**

But I’d be remiss if I didn’t also point you to Kerwin Datu‘s A network analysis approach to the Syrian dilemma on the Global Urbanist blog. He begins:

A chart by The Big Pharaoh doing the rounds of social media shows just how much of a tangled mess the Middle East is. But if we tease it apart, we see that the region is fairly neatly divided into two camps; it’s just that one of those camps is divided amongst itself. Deciding which of these internal divisions are fundamental to the peace and which are distractions in the short term may make the diplomatic options very clear.

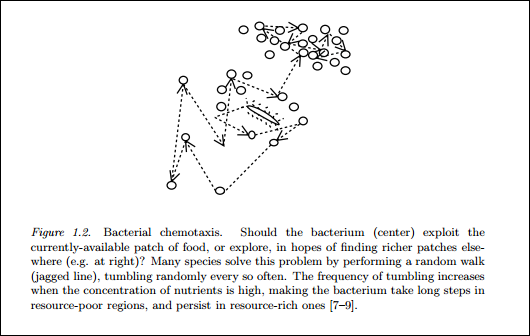

and goes on from there, offering a series of network graphs of which is the fourth:

from which he draws the following observation:

What can we do from this position? If the US decides to pursue a purely military route to remove Assad from power, it will incur the ire of Russia, Iran and Lebanese Shias, but it can do so with a broad base of support including the Syrian rebels themselves, Israel, Qatar, Turkey, Lebanese Sunnis, and even Al Qaeda. However if it chooses a diplomatic route to curry support to remove Assad it must isolate him in the above graph by making an ally out of Russia and/or Iran (assuming that making an ally out of Lebanese Shias would have little impact). Russia doesn’t hate the US but it does hate the Syrian rebels, making it an unpromising ally against Assad. Iran hates the Syrian rebels and the US hates Iran, but the Al Qaeda is a thorn in both their sides, making it a potential though unlikely source of cooperation.

Really, you and I should read the whole piece, and draw our own conclusions.

**

Or lack thereof. I’ll give the last tweet to Teju Cole, who articulates my own thoughts, too:

Grieved by Syria, but finding it hard to formulate an opinion about solutions. And that's OK, admitting the complexity in complex things.

— Teju Cole (@tejucole) August 28, 2013