Review: Poetry of the Taliban

Friday, July 20th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — poetry, humanity, dehumanizing, enmity and amity, image and likeness ]

.

I wrote this review-essay for Books & Culture: A Christian Review — the book review site associated with Christianity Today — where it was published earlier today. I am grateful to my old friend John Wilson for permission to cross-post it here.

I posted a reading of a single poem from the same anthology here on ZP in May: Change: a poem from The Poetry of the Taliban

CHARLES CAMERON

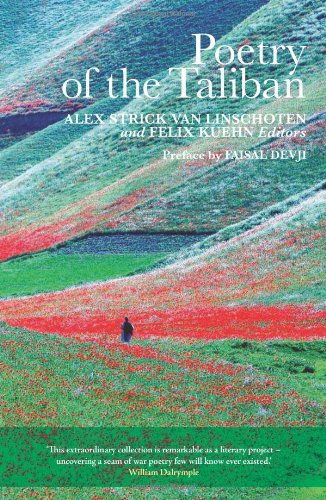

Poetry of the Taliban

Regarding the image and likeness.

Which heart’s voice is this that directly enters into my heart?

Which brute’s ears are these that are deaf to this?

Which sigh of the defenceless is shaking God’s domain?

The poet is Dr. Faizullah Saqib, and the poem is taken from an anthology of poetry written by the Taliban, our enemies. Could it not have been written when an earlier generation of mujaheddin, resisting the Soviet occupation, were our friends? What is this thing, enmity?

Poetry is not simply another weapon the Taliban have decided to use for wartime purposes. Poetry is integral to Afghan culture, and while there are “official” Taliban poems, the flourishing “unofficial” poetry of the Taliban is the place where their Afghan love of poetry takes flight, and the varied aspects of war have been woven into it in much the same way that helicopters have been woven into Afghan carpets: as part of the pattern. There’s an interesting quote on the Textile Museum of Canada website, in fact, relating to Afghan war rugs: “On their rugs flowers turned into cluster bombs, birds turned into airplanes.”

War changes us, war changes everything. Most significantly, I’d suggest, war changes the nature of those we label enemies. We do this anti-sacramental thing, we de-humanize them. As Samiullah Khalid Sahak writes in a poem in this volume,

They don’t accept us as humans,

They don’t accept us as animals either.

And, as they would say,

Humans have two dimensions.

Humanity and animality,

We are out of both of them today.

We are not animals,

I say this with certainty.

But,

Humanity has been forgotten by us,

And I don’t know when it will come back.

May Allah give it to us,

and decorate us with this jewellery,

the jewellery of humanity,

For now it’s only in our imagination.

War tends to do this; it strips people of their humanity—and the stripping tends to boomerang. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu put it,

when we dehumanize someone, whether you like it or not, in that process you are dehumanized. A person is a person through other persons. If we want to enhance our personhood, one of the best ways of doing it is enhancing the personhood of the other.

I said we “do this anti-sacramental thing, we de-humanize’ those we identify as the enemy. And there are really two significant points here, one to do with dehumanizing the other and its impact on us, while the other has to do with the sacramental—with humanizing and loving the other.

Brigadier General S. L. A Marshall, later the official historian of the European theater in World War II for the US Army, found by asking soldiers in the field that “out of an average of one hundred men along the line of fire only fifteen men … would take any part with the weapons.” As a Guardianarticle put it much later,

Marshall’s astonishing contention, debated vigorously ever since, was that about 75% of second world war combat troops were unable to fire their weapons on the enemy. Guns were discharged, but they would be deliberately aimed over the heads of the enemy. The vast majority of soldiers couldn’t actually kill. And, in the midst of combat, they became de facto conscientious objectors.

Marshall’s conclusion, contained in his 1947 book Men Against Fire, was that:

It is therefore reasonable to believe that the average and healthy individual—the man who can endure the mental and physical stress of combat—still has such an inner and usually unrealized resistance towards killing a fellow man that he will not of his own volition take life if it is possible to turn away from that responsibility.

And the result of this?

Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, a former Ranger who has taught psychology at West Point, wrote in 2007, “Since World War II, a new era has quietly dawned in modern warfare: an era of psychological warfare, conducted not upon the enemy, but upon one’s own troops.” That too is a sort of boomerang effect: we now find ourselves needing not only to dehumanize the enemy, but to desensitize (and how different is that?) ourselves.

Grossman, whose book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War is another major contribution to our understanding here, goes on to describe the “triad of methods used to enable men to overcome their innate resistance to killing” as including “desensitization, classical and operant conditioning, and denial defense mechanisms”:

During the Vietnam era millions of American adolescents were conditioned to engage in an act against which they had a powerful resistance. This conditioning is a necessary part of allowing a soldier to succeed and survive in the environment where society has placed him. If we accept that we need an army, then we must accept that it has to be as capable of surviving as we can make it.

But if society prepares a soldier to overcome his resistance to killing and places him in an environment in which he will kill, then that society has an obligation to deal forthrightly, intelligently, and morally with the psychological repercussions upon the soldier and the society. Largely through an ignorance of the processes and implications involved, this did not happen for Vietnam veterans—a mistake we risk making again as the war in Iraq becomes increasingly deadly and unpopular.

And what’s the basis for this? Sebastian Junger hung out for the better part of a year with troops in one of the most heavily contested parts of Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, describing what he saw there in the bookWar and the film Restrepo, which he directed. Junger commented not so long ago in the Washington Post:

I can’t imagine that there was a time in human history when enemy dead were not desecrated. Achilles dragged Hector around the walls of Troy from the back of a chariot because he was so enraged by Hector’s killing of his best friend. Three millennia later, Somali fighters dragged a U.S. soldier through the streets of Mogadishu after shooting down a Black Hawk helicopter and killing 17 other Americans …. Clearly, the impulse to desecrate the enemy comes from a very dark and primal place in the human psyche. Once in a while, those impulses are going to break through.

And:

They are very clear about the fact that society trains them to kill, orders them to kill and then balks at anything that suggests they have dehumanized the enemy they have killed.

But of course they have dehumanized the enemy—otherwise they would have to face the enormous guilt and anguish of killing other human beings …. It doesn’t work …, but it gets them through the moment; it gets them through the rest of the patrol.

People who fight wars find it easier to kill people they have dehumanized. Perhaps, as Junger suggests, it makes it easier to handle, for a while, the burden of having killed. But then comes the post-traumatic stress, the label “PTSD,” the rising tide of military suicides.

It’s almost easier for me to go to the sacramental side.

All terror is sacramental, Joseba Zulaika suggests in Terror and Taboo: The Follies, Fables, and Faces of Terrorism—an “outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace,” as evidenced by the stories of miracles recounted by bin Laden’s mentor Abdullah Azzam in his book, The Signs of the Merciful in the Jihad of Afghanistan.

It is with sacramental eyes, then, that we must understand and oppose terror, as William Cavanaugh in Torture and Eucharist suggests we should the “disappearances” and torture under the Pinochet regime in Chile. The issue, again, is that of personhood, of humanity, of the image and likeness.

Of which the poets Samiullah Khalid Sahak and Faizullah Saqib speak.

Sun Tzu in The Art of War advises us to know our enemy. Christ goes further, and instructs us to love. He instructs us in loving:

But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.

Somehow, we are to understand a new relationship of enmity with amity.

Perhaps the poetry of the Taliban can show us something of our enemy’s humanity, brutal and angelic by turns, as is that humanity with which we ourselves contend:

Like those who have been killed by the infidels,

I counted my heart as one of the martyrs.

It might have been the wine of your memory

that made my heart drunk five times.

The more I kept the secret of my love,

This simple ghazal spoke more of my secrets.

—Khairkhwa

Charles Cameron is a writer, teacher, and game designer.