Brutal Times 02

Sunday, October 2nd, 2016[ by Charles Cameron — on Kakutani, Hitler, Trump, Duterte, Aesop — and was Don Quixote a converso Jew? ]

.

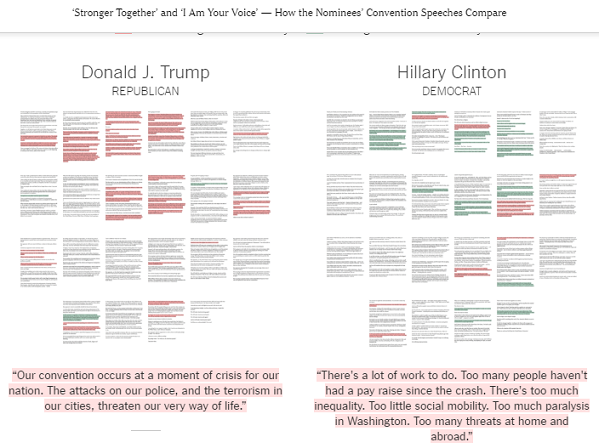

You don’t have to be an aging Kremlinologist to read between the lines, you don’t have to be a member of the target audience to be alert for dog-whistles, you don’t need a decoder ring to catch what the Washington Post calls “a thinly veiled Trump comparison” in Michiko Kakutani‘s New York Times review of Volker Ullrich‘s new biography, Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939.

However..

**

In his essay Persecution and the Art of Writing, Leo Strauss suggests that..

Persecution gives rise to a peculiar technique of writing and therewith to a peculiar type of literature, in which the truth about all crucial things is presented exclusively between the lines.

Such a style may or may not be evident in Michiko Kakutani’s review, but if it is there it is skilfully done — and not, I’d guess, in fear of persecution.

There’s a blunt equivalent now in use of social media in which, to quote but one example (others, equally or more distasteful, here):

“skittles” has come to refer to Muslims, an obvious reference to Donald Trump Jr.’s comparing of refugees with candy that “would kill you.”

Here, the purpose is to avoid algorithms that hunt down racist and other hateful comments on social media and expunge them — so the code words used include google, skype, yahoo and bing.

**

But wait. If you lob the h-word at Donald Trump, what ammunition will you have left for Rodrigo Duterte? Duterte is quite open about his admiration for Hitler.

But Trump?

David Duke wouldn’t mind:

The truth is, by the way, they might be rehabilitating that fellow with the mustache back there in Germany, because I saw a commercial against Donald Trump, a really vicious commercial, comparing what Donald Trump said about preserving America and making America great again to Hitler in Germany preserving Germany and making Germany great again and free again and not beholden to these Communists on one side, politically who were trying to destroy their land and their freedom, and the Jewish capitalists on the other, who were ripping off the nation through the banking system,

And Trump himself? From that 1990 Vanity Fair interview:

Ivana Trump told her lawyer Michael Kennedy that from time to time her husband reads a book of Hitler’s collected speeches, My New Order, which he keeps in a cabinet by his bed. Kennedy now guards a copy of My New Order in a closet at his office, as if it were a grenade. Hitler’s speeches, from his earliest days up through the Phony War of 1939, reveal his extraordinary ability as a master propagandist.

It’s worth noting that a few lines later, Trump declares:

If I had these speeches, and I am not saying that I do, I would never read them.

and that the interviewer, Marie Brenner, concedes:

Trump is no reader or history buff. Perhaps his possession of Hitler’s speeches merely indicates an interest in Hitler’s genius at propaganda.

**

So. Why Trump?

Mightn’t Kakutani simply be writing about Hitler and the new biography?

Oh, and if you insist on her having a second target, Trump may be nearer to hand, but Duterte is, well, more overt about his leanings..

Have you considered the Duterte possibility?

**

The range of uses to which “Aesopian language” — defined as:

conveying an innocent meaning to an outsider but a hidden meaning to a member of a conspiracy or underground movement

— can be put is enormous.

Here, to take your mind off contemporary politics and point it towards the higher levels of literary and religious thought, is Dominique Aubier’s comment on the Quixote, from Michael McGaha, Is There a Hidden Jewish Meaning in Don Quixote?

if one accepts that Cervantes’ thought proceeds from a dynamic engagement with the concepts of the Zohar, themselves resulting from a dialectic dependence on Talmudic concepts, which in turn sprang from an active engagement with the text of Moses’s book, it is then on the totality of Hebrew thought — in all its uniqueness, its unity of spirit, its inner faithfulness to principles clarified by a slow and prodigious exegesis — that the attentive reader of Don Quixote must rely in order at last to be free to release Cervantes’ meaning from the profound signs in which it is encoded.

You want to read the Quixote? How about spending a few decades in the Judaica section of your local university library first?

But then, those were brutal times.