J. Scott Shipman, the owner of a boutique consulting firm in the Metro DC area that is putting Col. John Boyd’s ideas into action, is a longtime friend of this blog and an occasional guest-poster.

Book Review: The New Digital Storytelling

by J. Scott Shipman

Bryan Alexander’s The New Digital Storytelling, Creating New Narratives With New Media is an excellent, highly readable, and comprehensive treatment of storytelling in our digital world. Dr. Alexander manages in 230 pages of text to capture the universe of available methods, processes, resources and tools available to storytellers, as of 2010. His 36 pages of notes and bibliography includes an exhaustive list of websites and sources used.

Dr. Alexander aimed his book at “creators and would-be practitioners,” storytellers looking for new digital ideas, to include teachers, marketers, and communications managers. Whatever your background, he assures in the introduction, “herein you will find examples to draw on, practical uses to learn from, principles to apply, and some creative inspiration.” I can’t speak for those in the target audience, but as one with but a casual interest in storytelling, I can say Dr. Alexander delivered! Over the course of the couple of days of reading, I came up with about a half-dozen ideas and discovered my MacBook Pro has a lot more under the hood than I ever appreciated or used.

That said, Dr. Alexander warns that his book is not a “hands-on manual” on the tech media discussed. In fact, he assumes the reader will not “be a technologist” and the material is presented accordingly. He says:

“The New Digital Storytelling straddles the awkward yet practical divide between production and consumption, critique and project creation.”

The book is divided into four parts:

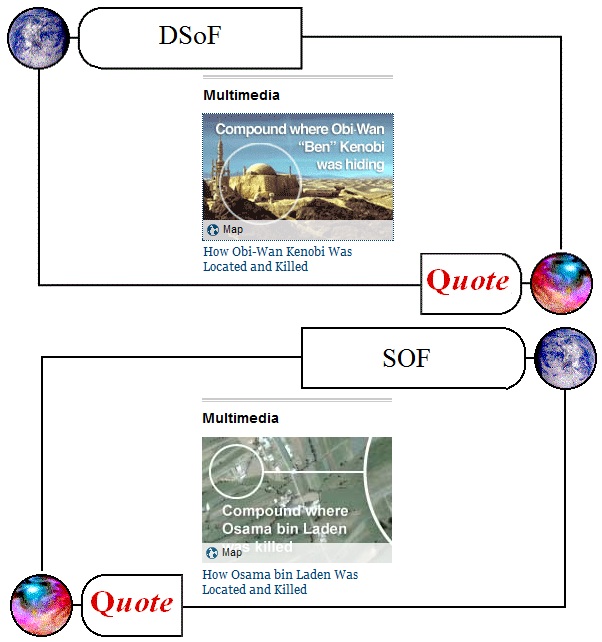

Part I Storytelling: A Tale of Two Generations

In Chapter 1 Dr. Alexander provides an unambiguous meaning to digital storytelling: “Simply put, it is telling stories with digital technologies.” The medium providing this review to you is my digital story about the book. But that is just the beginning; just about every digital device imaginable is being used to tell stories; blogs, social media, videos, and even in Twitter’s 140 character limit, storytelling genres are emerging [readers at zenpudit.com will recall Charles Cameron’s use of Twitter feeds following UBL’s death]. As Alexander points out, “no sooner do we invent a medium than do we try to tell stories with it.”

In Chapters 2 & 3, Dr. Alexander provides a history of digital storytelling in two parts; part one is what he calls “the first wave.” From foundations in the 70’s and 80’s (his reference to the 1983 movie War Games brought back memories) to the evolution and importance of hypertext. Alexander asks, “How do hypertexts work as digital stories? Users—reader—experience hypertext as an unusual storytelling platform. We navigate along lexia (“multiple readable chunks”) picking and choosing links to follow.” This point truly “clicked” for me; one of the pleasures of reading zenpundit.com is the ubiquity of supporting links and how sometimes these links lead to unexpected, but valuable adventures. Often I’ve landed in a place I would never have found if not for the first “story.” Alexander writes that Web 2.0 has allowed for “the ability to create content for zero software cost is historically significant, and now par for the course.” He points out with the ubiquity of hardware (both PCs and mobile devices) and the social element (social media, for example) a means of of delivery and an architecture are in place where potential storytellers have a low barrier to entry—to get their story out. Alexander includes gaming devices (mobile and console) in the review of the Web 2.0 phenomena.

Part II New Platforms for Tales and Telling

Chapter 4 is a comprehensive review of Web 2.0 storytelling and the fragility of systems existing today, but perhaps gone tomorrow. Dr. Alexander covers distinct types of blogs used in sharing stories; blogs are ubiquitous and the barriers to entry negligible. He covers epistolary novels and diary/journal-based stories and provides numerous examples. One example was News from 1930, which “posts selections from each day’s Wall Street Journal” during the early days of the Great Depression—in essence, a blog as a realtime history lesson. But as we know, the blogosphere is bigger than history, there also exists a market for various fictional stories which include reader interaction/collaboration. Also included are examples of character blogging (as Alexander notes: “Bloggers are characters”) where personalities are revealed over time in a serial nature. Twitter has developed into a unique format for storytelling, forcing the user to pack as much as possible in precious few words/characters. Wikis, social images and Facebook are also covered and explained in ways that made me think about “how” I use social media.

Chapter 5 covers in detail social media storytelling…and this is one of my favorite chapters. Alexander explains podcasts in a way that was accessible and in a way that made me want to “do” a podcast! A podcast is limited to audio, but a web video places a whole new spin on our ability to digitally tell our stories. Chapter 5 is rich in resources and insight.

In chapters 6 and 7 Alexander discusses gaming and storytelling. This may be the part of the book that was over my head (I’m dubious of the real utility of “gamification” in a meaningful/productive way). One sentence did jump off the page: “One key aspect of game-based storytelling is the immersion of the player in the story’s environment.” Indeed, “intimacy” is an enormous missing ingredient in more than storytelling and absolutely necessary in proficiency in just about any endeavor. One other sentence made a big impression: “Children also learn a deep secret about art, which is that the less detailed the representation of a character, the easier it is for us to identify with him or her.” I believe guys like the internet Oatmeal guy and the creator of Zen’s recent post have figured out this phenomena isn’t limited to children.

Part III Combinatorial Storytelling; or, The Dawn of New Narrative Forms

Chapters 8 through 11 covers the networked book, mobile devices, and alternate reality games. The networked book resonated with me because of something from my distant career on submarines (early 80’s); we would write a story where periodically storytellers would add a sentence and half to an evolving text. The results were always amusing and never predictable. Networked books sound very similar to our collaborative efforts 30 years ago, but with the ubiquity of digital tools, opportunities abound. For example “transmedia storytelling,” where “story content is distributed across multiple sites and media; the movie trilogy, an anthology of animated films, comics, computer games, a massively multiplayer online game, Web content, and additional DVD content.” This dispersion of story content and the variety of venues allows users a more “immersive experience”—-the intimacy Alexander described earlier. Mobile devices are literally changing just about every aspect of our world from political meetings, classrooms, clinics “now that those present can hit the Web for fact checking or peer support.” An excellent recent example was the squashed attempt of the United States Naval Institute’s board to change the organization’s mission. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn were used to get the word out to members who took action. New tablet devices will continue to drive this phenomena. Alexander’s treatment of alternate reality games revealed “worlds” created with our world by game participants of such products as Second Life.

Part IV Building Your Story

In the final chapters, Dr. Alexander provides example of “how to” build a digital story, using the classic Center for Digital Storytelling workshop model. For me, this was the most thought-provoking section. The description of how a workshop is conducted, the questions used to prompt creative/insightful “story-able” thought is worth the price of the book. Alexander inventories the software available for audio, images, video editing, publication, concept mapping, and other production tools. This inventory of tools describes the appropriateness of each with respect to the level of experience of the storyteller. Digital storytelling in education is covered in Chapter 14 and is a rich resource for parents and educators who want to leverage the digital world.

The New Digital Storytelling should be the standard guide for anyone who wants to use all the new digital gadgets available to tell their story; this book is an excellent one-stop resource. I plan to use what I’ve learned in the expansion of my family tree history to an A/V platform and have already built a to-do list to get started.

One closing thought; the irony isn’t lost that this “book” about digital storytelling is made of paper, glue, and ink. I can only imagine what an adventure this would be if presented digitally where all the links were connected…a digital story on how to tell digital stories.

The New Digital Storytelling comes with my highest recommendation. Get this book, use those tools, and tell your stories.