Iconic: compare and contrast III

Saturday, December 24th, 2011[ by Charles Cameron – Iraq war, beginning and ending, analytic power of similarity ]

.

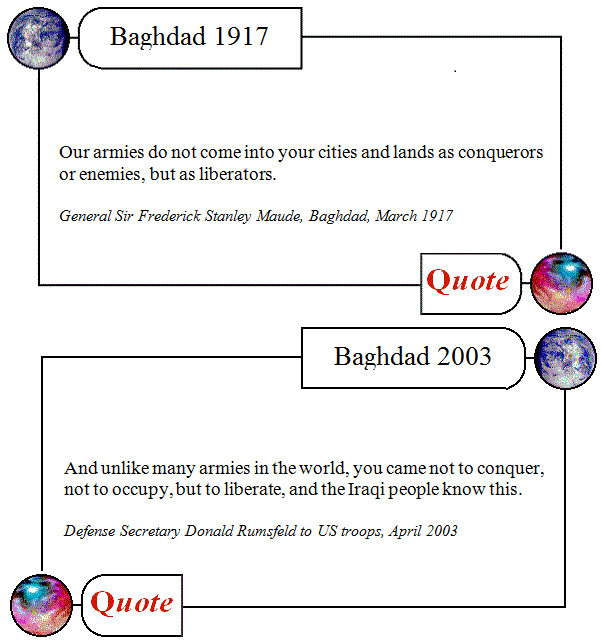

I’ve thanked Zen for his Iconic Compare and Contrast post already, but I’d like to run with his juxtaposition of images from the end of the Iraq war, and book-end it with an early DoubleQuote of mine from the beginning, thus:

That’s the beginning of the war, as I saw it “binocularly” — and here’s its ending, as Zen captured it:

Different though they are — one verbal, one visual — I think they go well together. I think they belong together.

But that’s essentially an aesthetic intuition.

*

And — apart from thanking Zen — that’s the thing I want to talk about.

The two quotes, eighty-six years apart, about an (anglophone) army in Baghdad coming there to liberate, not to conquer, are similar enough that they should give us pause for thought. They challenge us to think long and hard about the similarities between the two situations — and they challenge us to think no less hard and long about their differences.

Likewise, it’s the similarities between the two images Zen chose — of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan and the US exit from Iraq — that give that juxtaposition its power. And Zen has chosen very carefully:

Not only are there two lines of vehicles stretching back from the foreground away into the distance in each image, but the angle from which the two columns are seen is about the same — and there are even two “tracks” in each photo reinforcing the vanishing point — two tracks to the right of the vehicles in the Afghan photo, the edge of the road and a what looks like the shadow of an overhead cable in the photo from Iraq.

*

But let’s take this a bit further. The following juxtaposition is every bit as much a juxtaposition of the Soviet and American withdrawals as the pair of images Zen picked, but this time we have an aerial view of the US convoy — so the visual “rhyme” between the two images is no longer there — and even though the aerial shot is an intriguing one, what a difference that makes!

There’s nothing in that juxtaposition to make you go, yes!

On the level of what’s being referred to, the troop withdrawals from Afghanistan and Iraq, this pair of images has the same properties as the two images that Zen selected. But it doesn’t capture our attention in nearly the same way.

And the same would have been true if I’d picked a different sentence from Rumsfeld‘s speech to juxtapose with General Maude‘s “not as conquerors or enemies but as liberators” — such as, “You’ve unleashed events that will unquestionably shape the course of this country, the fate of the people, and very likely affect the future of this entire region.” I’d still be comparing and contrasting two speeches from the beginnings of two occupations of Baghdad. But there’d be no oomph to the comparison.

*

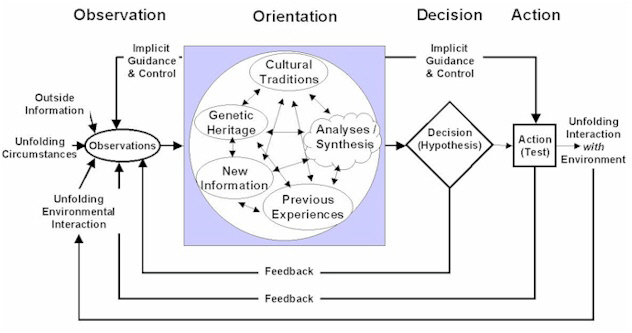

Because — and this is what I am trying to get at, the basic principle of HipBone analysis and what distinguishes it from otherwise similar modes of brainstorming and mind-mapping — the recognition of pattern, of salient sameness, of close parallelism or opposition is the criterion for success or failure in a HipBone-style juxtaposition.

Zen’s graphic example has that closeness — even down to those two parallel tracks beside and to the right of the vehicles. My two quotes from Maude and Rumsfeld have that. And it’s that closeness of match that makes a juxtaposition powerful.

Analogy works this way, rhyme works this way, fugue works this way, graphic match (in cinematography) works this way — it’s basic to the arts, basic to rhetoric, and basic to the way our analogically-disposed minds think.

It is not a method for arriving at conclusions, it’s a method for posing questions. And it sits right at the juncture where analysis admits it is not a science but an art.