Dr. John Nagl, president of CNAS, lead author of The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual , retired lieutenant colonel and top COIN expert, has penned an important review of Accidental Guerrilla

, retired lieutenant colonel and top COIN expert, has penned an important review of Accidental Guerrilla by Col. David Kilcullen, in the prestigious British journal RUS

by Col. David Kilcullen, in the prestigious British journal RUS I. Unfortunately, at present no link is is available, but my co-author Lexington Green is a subscriber and sent me a copy of the review, which I read last night. I now look forward to reading Kilcullen firsthand and have put Accidental Guerrilla near the top of my summer reading List.

I. Unfortunately, at present no link is is available, but my co-author Lexington Green is a subscriber and sent me a copy of the review, which I read last night. I now look forward to reading Kilcullen firsthand and have put Accidental Guerrilla near the top of my summer reading List.

I state that Nagl’s review is important because beyond the descriptive element that is inherent in a review, there is a substantive aspect that amounts to an effective act of policy advocacy. First, an example of Nagl’s descriptions of Kilcullen’s arguments:

We do not face a monolithic horde of jihadis moti vated by a rabid desire to destroy us and our way of life (there are some of these, although Kilcullen prefers to call them takfiris); instead, many of those who fight us do so for conventional reasons like nationalism and honour. Kilcullen illustrates the point with the tale of a special forces A-Team that had the fight of its life one May afternoon in 2006. One American was killed and seven more wounded in a fight that drew local  fighters from villages five kilometres away who marched to the sound of the guns – not for any ideological reason, but simply because they wanted to be a part of the excitement. ‘It would have shamed them to stand by and wait it out’, Kilcullen reports

fighters from villages five kilometres away who marched to the sound of the guns – not for any ideological reason, but simply because they wanted to be a part of the excitement. ‘It would have shamed them to stand by and wait it out’, Kilcullen reports

Tribal and even “civilized” rural people, often find ways of making social status distinctions that relate to behaviour and character rather than or in addition to the mere accumulation of material possessions (Col. Pat Lang has a great paper on this subject, “How to Work with Tribesmen“). We can shorthand them as “honor” cultures and they provide a different set of motivations and reactions than, say, those possessed by a CPA in San Francisco or an attorney in Washington, DC. People with “honor” are more obviously “territorial” and quick to defend against perceived slights or intrusions by unwelcome outsiders. This is a mentality that is alien to most modern, urbanized, 21st century westerners but it was not unfamiliar all that long ago, even in 19th and early 20th century, Americans had these traits. Shelby Foote, the Civil War historian, quotes a captured Southern rebel, who responded to a Union officer who asked him, why, if he had no slaves, was he was fighting? “Because you are down here” was the answer.

While relatively short and designed, naturally, to help promote a book by a friend and CNAS colleague, Dr. Nagl has also taken a significant step toward influencing policy by distilling and reframing Dr. Klicullen’s lengthy and detailed observations into a reified and crystallized COIN “doctrine”. A digestible set of memes sized exactly right for the journalistic and governmental elite whose eyes glaze over at the mention of military jargon and who approach national security from a distinctly civilian and political perspective:

There is much first-hand reporting in this book, based on Kilcullen’s [Robert] Kaplan-esque habit of visiti ng places where people want to kill him. After chapters detailing his personal experience in Afghanistan and Iraq, he returns to his doctoral fieldwork in Indonesia, discusses the insurgencies in Thailand and Pakistan and evaluates the complicated plight of radical Islam in Europe. While all of these confl icts are related to each other, they are not the same, and cannot be won based on a simplistic conception like the global War on Terror; instead, the enemy in each small war must be disaggregated from the whole, strategy in each based on local conditions, motivations, and desires. One size does not fit all, and there are many grey areas. A ‘with us or against us’ approach is likely to result in far more people than otherwise being ‘against us’ in these conflicts.

John Boyd would have agreed that isolating our enemies and winning over groups as allies is much preferred to needlessly multiplying our enemies. That paragraph is more or less boilerplate in the COIN community but this RUSI review is aimed not at them but at political decision makers, national security bureaucrats, diplomats and elite media and constituted a necessary set up by Nagl for “The Kilcullen Doctrine” [bullet points are my addition to Nagl’s text, for purposes of emphasis]:

….In direct oppositi on to the ideas that drove American interventi on policy two decades ago, Kilcullen suggests ‘the anti -Powell doctrine’ for counter-insurgency campaigns.

-

First, planners should select the lightest, most indirect and least intrusive form of intervention that will achieve the necessary effect.

-

Second, policy-makers should work by, with, and through partnerships with local government administrators, civil society leaders, and local security forces whenever possible.

-

Third, whenever possible, civilian agencies are preferable to military intervention forces, local nati onals to international forces, and long-term, low-profile engagement to short-term, high-profile intervention.

New doctrines emerge because ideas are articulated at the moment in time when they both fit the circumstances and the intended audience is ready to accept their implications. George Kennan, the father of Containment in 1946-1947 had attempted to give the State Department and the Roosevelt administration essentially the same advice about Soviet Russia in the 1930’s and the reaction of the White House was to order the State Department’s Soviet document collection destroyed and exile critics of Stalin like Kennan from handling Eastern European affairs ( Kennan saved the collection by storing it in his attic). Neither Stalin’s nature nor Kennan’s opinion of the USSR changed much in the next decade, but the willingness of American liberal elites to consider them did, making Containment doctrine a reality.

The post-Cold War, Globalization era elite is in the ready state of mind for a “Kilcullen Doctrine”. They are ready to hear it because systemic uncertainties have made them justifiably skeptical of old prescriptions and they are seeking new perspectives the way the Truman White House invited Kennan’s Long Telegram. This situation is both good and bad in about equal measure.

The good comes from the fact that the Kilcullen Doctrine is operationally sound, at least for specifically handling issues of complex insurgencies. It is also politically astute, in that it encourages statesmen and military leaders to first tinker with minimal measures while listening acutely for feedback instead of charging in like a bull in a china shop, to empower locals rather than engaging in the military keynesianism equivalent of enabling welfare dependency, as the U.S. did in South Vietnam and initially in Iraq. Kilcullen is also a reluctant interventionist, a healthy sentiment, albeit one unlikely to survive in doctrinal form.

The bad is multifaceted. None of these are dealbreakers but all should be “handled” by the COIN advocates of a “Kilcullen Doctrine”:

First, Kilcullen’s three principles are an operational and not a genuinely strategic doctrine. In fairness, no major COIN advocate has ever said otherwise and have often emphasized the point. The problem is that a lot of their intended audience – key civilian decision makers and opinion shapers in their 30’s-50’s often do not understand the difference, except for a minority who have learned from bitter experience. Most of those who have, the Kissingers, Brzezinskis, Shultzes etc. are elder statesmen on the far periphery of policy.

Secondly, this operational doctrine requires a sound national strategy and grand strategy if it is to add real value and not merely be a national security fire extinguisher. Kilcullen may say intervention is unwise but that is really of no help. Absent a grand strategy with broad political acceptance, policy makers, even professed isolationists, will find situational (i.e. domestic political reasons) excuses for intervention on an ad hoc basis. That George W. Bush entered office as a sincere opponent of “nation-building” and proponent of national “humility” should be enough to give anyone pause about a president “winging it” by reacting to events without a grand strategy to frame options and provide coherence from one administration to the next.

Thomas P.M. Barnett, a friend of this blog, has been articulating a visionary grand strategy since 2004 in a series of books, the latest of which is Great Powers: America and the World After Bush , where he essentially models for the readers how a grand strategy is constructed from historical trajectories and economic currents to make the case. Barnett’s themes have a great consilience with most of what COIN advocates would like to see happen, but Dr. Barnett’s public example of intellectual proselytizing and briefing to normal people outside of the beltway is even more important. Operational doctrine is not enough. It is untethered. It will float like a balloon in a political wind. It is crisis management without a destination or sufficient justification for expenditure of blood and treasure. If these blanks are not filled in, they will be filled in by others.

, where he essentially models for the readers how a grand strategy is constructed from historical trajectories and economic currents to make the case. Barnett’s themes have a great consilience with most of what COIN advocates would like to see happen, but Dr. Barnett’s public example of intellectual proselytizing and briefing to normal people outside of the beltway is even more important. Operational doctrine is not enough. It is untethered. It will float like a balloon in a political wind. It is crisis management without a destination or sufficient justification for expenditure of blood and treasure. If these blanks are not filled in, they will be filled in by others.

COIN advocates will have to bite the bullet of working on national strategy and grand strategy, building political coalitions, speaking to the public and wading into geoeconomics and the deep political waters of the long view. For a some time, they have had the excuse that as uniformed officers, such questions were above their pay grade – and this was the scrupulously, constitutionally, correct position, so long as that was the case.

That era is swiftly passing and most of these brilliant military intellectuals now have (ret.) in their titles and wear business suits rather than fatigues. COIN is not an end in itself. The horizon is much wider now and we should all be ready to pitch in and help.

ALSO POSTING ON THIS TOPIC:

SWJ Blog – Weekend Reading and Listening Assignment

Thomas P.M. Barnett – Safranski on Nagl on Kilcullen

The Strategist – Sunday reflection: on “The Accidental Guerrilla”

MountainRunner –Recommended Reading: Kilcullen Doctrine

Abu Muqawama – Dogs and cats, living together. Mass hysteria!

HG’s World – A Brief on the Accidental Guerrilla by Zenpundit

Information Dissemination – New Doctrines Without Strategic Foundations

Galrahn is right, I have not quite fleshed things out in my post and could use the help. He’s also clarified that the discussion needs to shift to the “why”, the objectives, with which I was not particularly clear by the use of “strategy” which means different things to different people, even those versed in military affairs.

.

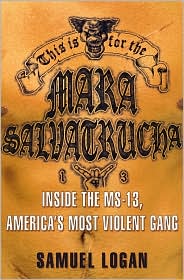

crew of MS-13 and a crime committed that ultimately allows law enforcement to penetrate what had been a highly secretive, as well as extremely violent, transnational street gang rooted in Central American immigrant communities.

crew of MS-13 and a crime committed that ultimately allows law enforcement to penetrate what had been a highly secretive, as well as extremely violent, transnational street gang rooted in Central American immigrant communities.

I

I fighters from villages five kilometres away who marched to the sound of the guns – not for any ideological reason, but simply because they wanted to be a part of the excitement. ‘It would have shamed them to stand by and wait it out’, Kilcullen reports

fighters from villages five kilometres away who marched to the sound of the guns – not for any ideological reason, but simply because they wanted to be a part of the excitement. ‘It would have shamed them to stand by and wait it out’, Kilcullen reports