Review: Tolkien Maker of Middle-Earth

Tuesday, March 26th, 2019[mark safranski / “zen“]

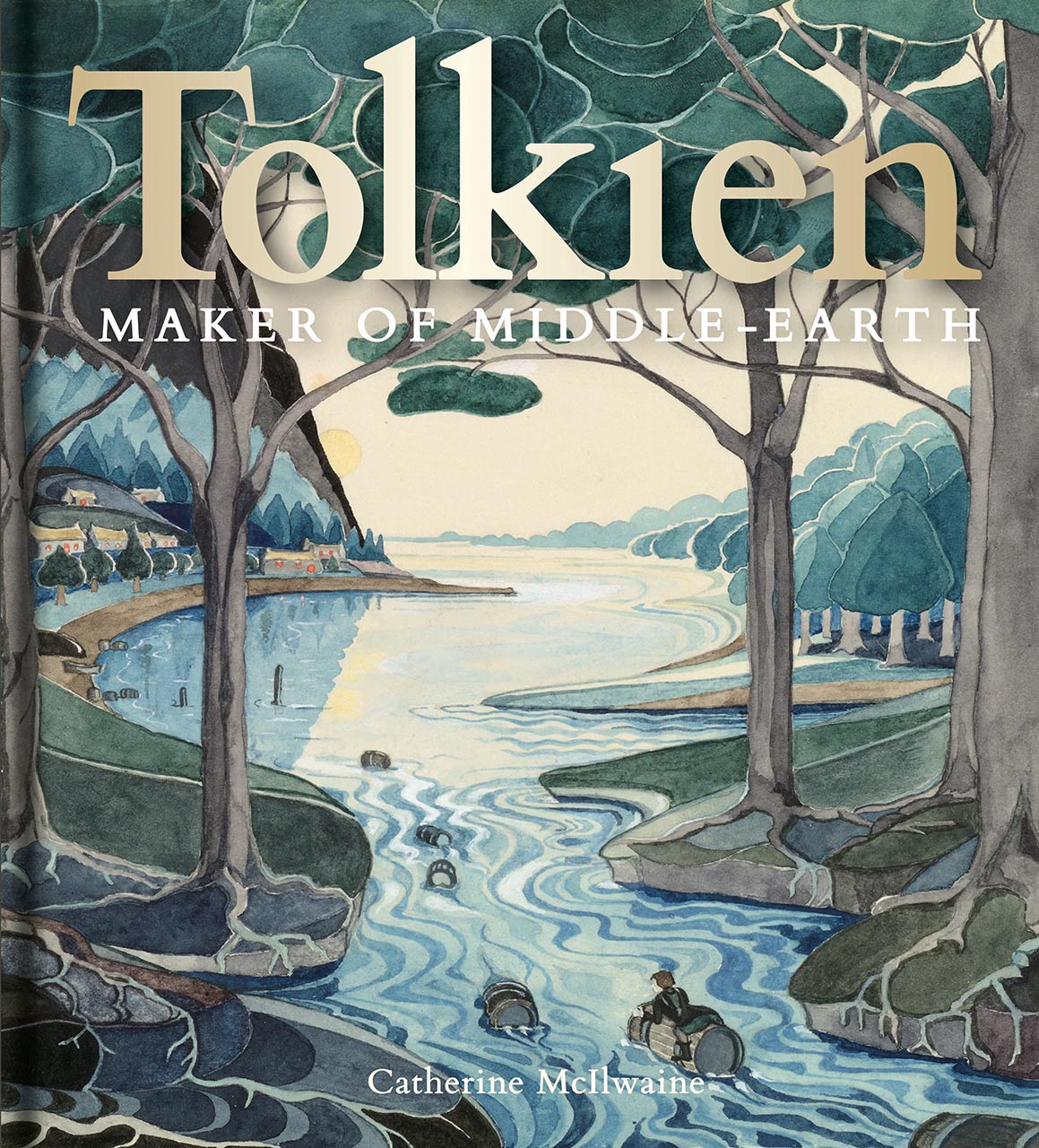

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth by Catherine McIlwaine

I have been a lifelong fan of The Lord of the Rings and of J.R.R. Tolkien generally, Tolkien being one of a small handful of writers who were formative influences in my youth and who remain favorites today. Therefore, I was quite pleased when Scott Shipman alerted me to the publication of Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth by Catherine McIlwaine. Other than Christopher Tolkien himself, there could not have be en a better author and editor of a retrospective look at Tolkien’s creation of Middle-Earth than McIlwaine, who is the longstanding Tolkien Archivist of the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. The book, which includes original essays by Tolkien scholars, including McIlwaine herself, is a companion catalog to the major exhibition of the extensive Tolkien collection held by Bodleian:

The Bodleian Library will publish Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth as a companion to the forthcoming exhibition of the same name on 1 June 2018.

The “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth” exhibition will be held at the Weston Library, part of the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford, from 1 June to 28 October 2018. It will feature an unprecedented array of Tolkien materials – manuscripts, paintings and maps – sourced from the Bodleian’s archive, Marquette University in Milwaukee (Wisconsin) and private collections.

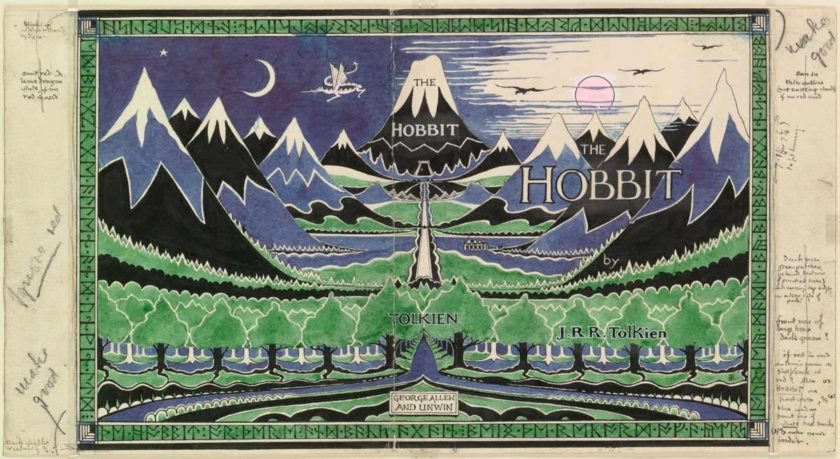

According to The Bookseller, the companion book will be “the largest collection of material by J.R.R. Tolkien in a single volume”. It will also include “new” material, including draft manuscripts of The Hobbit, Middle-earth illustrations and paintings by Tolkien, and letters from admirers such as W.H. Auden, Joni Mitchell and Iris Murdoch.

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth is both a serious addition to any Tolkienphile’s library as well as a 411 page coffee table book full of resplendent pictures of Tolkien’s handmade artwork, annotated maps, marginalia, correspondence with publishers and authors, calligraphic character sketches from the legendarium and photographs from J.R.R. Tolkien’s life, many published for the first time. The essays, by John Garth, Verlyn Flieger, Carl F. Hostetter, Tom Shippey, Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull as well as McIlwaine are thoughtful and reflective investigations and commentary on par with what readers would find in Philip and Carol Zaleski’s The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings. I particularly liked Shippey’s “Tolkien and that noble Northern spirit” and Garth’s ” Tolkien and the Inklings” but the entire catalog section contains informative and explanatory passages about the immense mythic legendarium that Tolkien created.

Friend of ZP, T. Greer has weighed in at The Scholar’s Stage with a superb post about the importance of J.R.R. Tolkien as a literary figure that is a must read for fans of Middle-Earth:

….Here I’ve sketched out an archetypal template. This is the template upon which the vast majority our era’s hero-tales are crafted. This is the story of Harry Potter, Katniss Everdeen, Luke Skywalker, and Jack Ryan. It is Captain America and Spiderman. It is the central trope of science fiction, fantasy, international thrillers, super hero stories, and their “YA literature” counterparts. It is the myth that drives the imaginations of our times.

For all of this we have John Ronald Reuel Tolkien to thank. I am sympathetic to the argument that Tolkien is the seminal Anglophone author of the 20th century. Perhaps his literary craft is deft enough to deserves that title. Perhaps it is not. Either way I wager that in a few centuries time when our descendants’ literary memory has collapsed our age down to one author (as we have done with the ages of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton), Tolkien will be the man remembered. This is not just because Tolkien’s works have been fantastically popular, even decades after its first publication, and in cultural milieus quite divorced from its creation. Nor it is because in Tolkien we find the genesis of so many of our era’s most popular genres (fantasy, science fiction, role playing games, and so forth). Tolkien’s influence is both subtler and more fundamental than this. Tolkien redefined the way popular literature treats many of its most common themes. This post looks at only one of those themes, but I am comfortable with the contention that Tolkien’s work embodies an entire era’s way of understanding the world. It is hard to say if Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings actually created the central cultural currents of our age or if it is simply their most prominent and enduring incarnation. Either way, Tolkien’s work is here to stay.

Readers familiar with Lord of the Rings will immediately see the connections between my opening sketch and the tale of Tolkien’s ring-bearer. I am not going to devote an entire essay to this topic—a great deal has already been written about Tolkien’s conception of good and evil, power, corruption, innocence, and heroism, and I see no reason to repeat others’ feats here—but I will emphasize two points that deserve strong restatement.

The first point: An aversion to glory is not just the defining character trait of the novel’s central hero. The distinction between greatness and power as goods to be strived for versus greatness and power as burdens to be carried is the distinction that sets apart almost of all of the novel’s protagonists from their foils. It is the defining difference between Frodo and Smeagol, Faramir and Boromir, Aragorn and Denethor, and Gandalf and Saruman. The second trait saves Galadriel in exile; the first corrupts Sauron anew after his master’s defeat. If one is allowed to describe objects as foils, this same distinction sets Sauron’s rings, key to his strategy for corrupting Middle Earth, as a foil to the methods of the ‘wizards’ sent from Western lands to save Middle Earth….

Read the rest here.

Tolkien’s influence will be here to stay for many an age.