For Jim Gant, On the Resurrection, 04

Wednesday, April 25th, 2018[ by Charles Cameron — in thre “expansive” phase of this exploration ]

.

In her mysteriously beautiful detective procedural set in a Québécois monastery, The Beautiful Mystery: A Chief Inspector Gamache Novel, Louise Penny arrives, about midway through her tale, at this sentence:

When Frère Mathieu brings out his bomb, the abbot brings out his pipe. One weapon is figurative, and the other isn’t.

I’m riveted.

**

Because the phrase “One .. is figurative, and the other isn’t” is like a koan for me — a nut that if I could crack it would also explain such deep mysteries as:

“This is my body .. this is my blood” — one interpretation of “body & blood” is figurative, while the other isn’t? and: “he died ..and on the third day he rose again” — one death is figurative, and the other isn’t?

Resurrection as myth, resurrection as history?

**

You might think I’m being fanciful, but just yesterday the Comey notes became accessible, and we find this exchange between the FBI Director and the President:

The President then wrapped up our conversation by returning to the issue of finding leakers. I said something about the value of putting a head on a pike as a message. He replied by saying it may involve putting reporters in jail. “They spend a few days in jail, make a new friend, and they are ready to talk.” I laughed as I walked to the door Reince Priebus had opened.

I trust Comey‘s “head on a pike” is figurative, and it sounds like the other — Trump‘s “putting reporters in jail” — isn’t.

The thing about language is that it’s polyvalent, polysemous –and that inherent ambiguity is seldom more significant than when making or interpreting threats, scriptures, or poems.

**

So I could take this post in the direction of a discussion of the ruthless politics of Washingtom, the Kremlin, Pyongyang, Baghdad, and or Beijing..

Or into the exegesis of the Eucharist, Resurrection, Adamic Creation stories. In matters Biblical, the question “one reading fictitious, while the other, literal, isn’t?” more or less covers the major theological division of our times..

On this, see the Catholic Catechism (115-117) for a more Dantesque elucidation:

The senses of Scripture

According to an ancient tradition, one can distinguish between two senses of Scripture: the literal and the spiritual, the latter being subdivided into the allegorical, moral and anagogical senses. The profound concordance of the four senses guarantees all its richness to the living reading of Scripture in the Church. The literal sense is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation: “All other senses of Sacred Scripture are based on the literal.” The spiritual sense. Thanks to the unity of God’s plan, not only the text of Scripture but also the realities and events about which it speaks can be signs. The allegorical sense. We can acquire a more profound understanding of events by recognizing their significance in Christ; thus the crossing of the Red Sea is a sign or type of Christ’s victory and also of Christian Baptism. The moral sense. The events reported in Scripture ought to lead us to act justly. As St. Paul says, they were written “for our instruction”. The anagogical sense (Greek: anagoge, “leading”). We can view realities and events in terms of their eternal significance, leading us toward our true homeland: thus the Church on earth is a sign of the heavenly Jerusalem.

Two senses of Scripture: the literal and the spiritual — one is figurative, like Frère Mathieu’s bomb in Ms Penny’s novel, while the other, like the abbot’s lead pipe, isn’t?

The Jesus of History, the Christ of Faith?

Or all this might take another turn, with a morph into poetry..

**

Or history. Here’s another phrase that’s “riveting” for, I think, the same reason as that phrase “One weapon is figurative, and the other isn’t”:

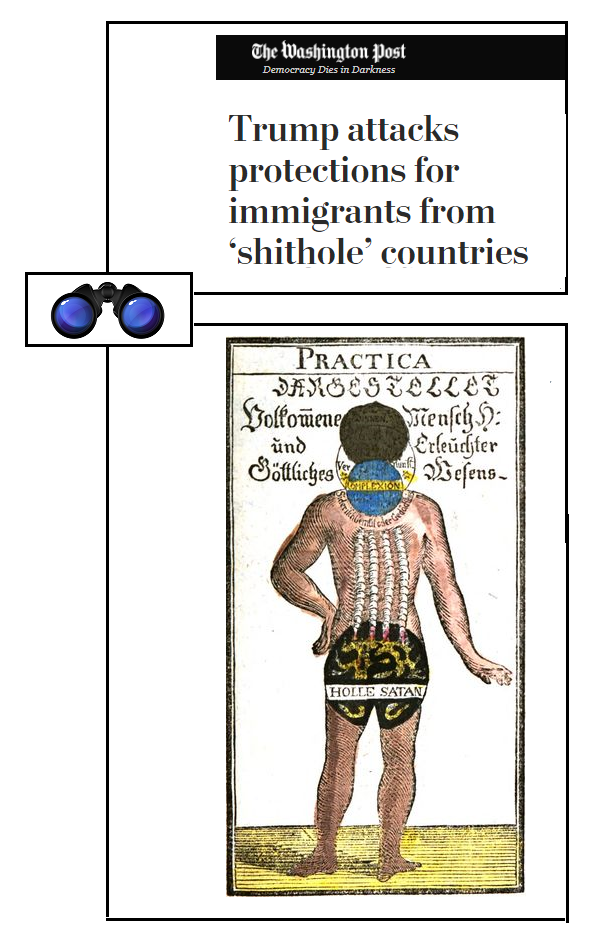

Pamphlets were both a cause and a tool of violence.

A “cause .. of violence” — it t (a pamphlet) incites it. And “a tool of violence” — it’s (at least figuratively) a bludgeon in itself. Hm. I hope that makes sense.

In any case, I’ve got my eye out for other examples that neatly juxtapose word and deed, as though words aren’t deeds — “speech acts” as the philosophers say. What I’m getting at, eventually, is the nature of sacrament — “an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace” — which is deeply tied up with simile, metaphor, and metamorphosis — “this is my body .. this is my blood”.

And that quote about pamphlets? Its from a fascinating New Yorker piece, How We Solved Fake News the First Time by Stephen March, which compares fake news on the internet today with fake news in the time of the pamphleteers, and contains this remarkably “ancient and modern” observation:

There is nothing more congruent to the nourishment of division in a State or Commonwealth, then diversity of Rumours mixt with Falsity and Scandalisme; nothing more prejudicial to a Kingdome, then to have the divisions thereof known to an enemy.

So, -ismes were already infesting the language like kudzu grass — mixed simile? — back in 1642. And an enemy? Think Putin, ne?

On which playful note, drawn from seven years before the martyrdom of King Charles I at the hands of the Puritans, I’ll leave you.

For now.