[ by Charles Cameron — at the intersection of filmcraft, tradecraft, and gameplay ]

.

**

IBM Fellow Jeff Jones has a powerful insight into puzzles and analytics which I explored in one of my early guest posts here, A Hipbone Approach to Analysis III. I quoted him thus:

The first piece you take out of the box and place on the work surface requires very little computational effort. The second and third pieces require almost equally insignificant mental effort. Then as the number of pieces on the table grows the effort to determine where the next piece goes increases as well. But there is a tipping point where the effort to determine where to place the next piece gets easier and easier … despite the fact the number of puzzle pieces on the table continues to grow.

and — being a theologian and poet, hence interested in creative leaps — I threw this in for bonus points, since in it he talks about epiphanies:

Some pieces produce remarkable epiphanies. You grab the next piece, which appears to be just some chunk of grass – obviously no big deal. But wait … you discover this innocuous piece connects the windmill scene to the alligator scene! This innocent little new piece turned out to be the glue.

**

That, being (at least a little) past — I was quoting Jonas back in 2010 — is prologue.

Yesterday I was listening to Nada Bakos, ex-CIA analyst and targeter, and more recently one of the stars of the HBO documentary Manhunt, which just won an Emmy — and which I have written about twice here on Zenpundit, first in Manhunt: Radicalization, & comprehending the full impact of dreams, and then in Manhunt: religion and the director’s eye.

Chelsea Daymon interviewed Nada Bakos on yesterday’s Loopcast, and I’d just got to the point, one minute and thirteen seconds in, where Bakos said the words that triggered my urgent need to reconnect with Jonas and his puzzle insights. She says:

It’s not unlike what an investigative journalist would do, when you’re piecing together an intelligence picture. You’re looking at disparate bits of information, and you’re trying to form them to make a puzzle. So from our perspective at the Agency, we were looking at it from signal intelligence, to human intelligence, to technical collection, foreign intel services — across the board, we were gathering this information from a variety of different sources. And any one of those pieces of information. in and of itself, may look innocuous, or not representative of what we’re trying to find, but when you add it to the larger puzzle, that’s when you can see if its going to fit. So it’s hard to sift through the chaff to find your actual information that you need to piece together.

I also wrote briefly about Manhunt in A feast of form in my twitter-stream today, quoting Bakos’ colleague Cindy Storer:

Even in the analytical community there’s a relatively smaller percentage of people who are really good at making sense of information that doesn’t appear to be connected. So that’s what we call pattern analysis, trying to figure out what things look like. And those people, you really need those people to work on an issue like terrorism, counternarcotic, international arms trafficking, because you’ve got bits and pieces of scattered information from all over the place, and you have to try to make some sense of it. … That takes this talent, which is also a skill, and people would refer to it as magic — not the analysts doing it, but other people who didn’t have that talent referred to it as magic.

Storer’s “magic” and Jones’ “epiphany” seem to me to have a great deal in common…

**

[ and yes, personal disclosure, I’ve been working for almost 20 years on games that teach that kind of magic, the whole of that kind of magic across all domains, and nothing but that kind of magic. ]

**

Back to Nada Bakos, and a crucial distinction between two types of analytic puzzle-solving:

From a predictive standpoint, if you’re looking at trying to gauge when or if an attack is going to happen, that is really difficult, and you’re going about looking at the data in a very different way. Because if you have a piece of intelligence that said that there will be an attack, but you don’t know the timing or location, your focus is going to be strictly on those two pieces.

That’s narrow focus. Wide focus, by contrast?

When you’re trying to look at an overall picture, you’re not — this is typical of intelligence gathering, when you don’t know what you have in front of you — you’re letting the information tell you what the picture is going to be. And that’s the objective challenge for intelligence analysis, and that’s what the Agency tries to drill into their analysts, to always let the information lead you, rather than you lead the information, so you’re…

**

Wait a moment, though — I’d like to come back to that — but just for the record, here’s what looks to be a parallel use of “leading” from a legal definition…

LEADING QUESTION, evidence, Practice. A question which puts into the witness’ mouth the words to be echoed back, or plainly suggests the answer which the party wishes to get from him. 7 Serg. & Rawle, 171; 4 Wend. Rep. 247. In that case the examiner is said to lead him to the answer. It is not always easy to determine what is or is not a leading question.

I’m hypothesizing that the idea here is, in effect, “to always let the witness lead you, rather than you lead the witness” — in the interests of justice, not of prosecution or defense… And that “justice” in this case parallels “objectivity” in the case of intelligence analysis.

Analysts may yawn and attorneys quietly splutter at this truism — yet when the same pattern crops up in two distinct fields, you can bet it has more general application. From an intel standpoint, it’s a matter of avoiding your own biases and assumptions, and dealt with as such in Heuer. In the arts, it’s this need to avoid painting what one thinks what one knows, rather than what one sees, that’s behind Betty Edwards‘ instruction to her students to draw an upside-down photo of Albert Einstein, as in her book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, see p. 51. In music, it’s what permits the fresh interpretation of the Goldberg Variations by Glenn Gould, 1955 — and then years later in 1981, but Gould again — so very different from all previous interpretations.

It’s the stuff of creativity, and at its highest pitch, the stuff of genius.

**

But let Ms Bakos continue… Here’s another distinction she draws for us:

From a targeting perspective, your focus is, operationalizing the analysis. So you’re taking all that big picture and you’re doing something about it, so that is your intent from the get-go.

When you’re a traditional analyst, you’re actually writing pieces for the policy maker, and you’re adding to the larger picture so they can make decisions based upon that intelligence.

The second of these is clear enough, but I’d have a question for Ms Bakos about the first.

Roughly speaking –and I know the answer is likely to be a bit more complex than my formulation of the question — does this mean t hat the policy maker has by this point signed off on a “do whatever’s needed in your best judgment to achieve the stated goal”? — and if so, where is the threshold where targeting and execution take over from decision-making, in a Clausewitzian extension of the politics by other means?

**

Towards the very end of the interview, and having covered a number of topics that were specific to Iraq and al-Zarqawi and thus not pertinent to my interests here, Ms Bakos asks:

How do we effect change, how do we actually deprogram people to get out of these groups, these regional groups, this ideology, and I think we haven’t effectively tapped into that, yet. I think we’re always fighting yesterday’s war. So, I think we need to start looking forward as well: What’s the way out? Are we working with host governments to figure out how we help people to get out of al-Qaida, how do they get out of the situation that they’re currently in — because once they’re in I think it’s very difficult, for some of these younger followers, if they’ve become disenchanted, to move on.

That’s something I feel passionate about, since Leah Farrall posted a series on Children, jihad, agency, and the state of counter terrorism making much the same point in considerable, painful detail. I invite you to open that link in another window and bookmark it for later reading.

If I’m reading both Ms Bakos and Leah right, this is a serious and underappreciated issue, and one that is both humane and eminently practical.

** ** **

Okay, that’s the gist of what Manhunt tells us about the analytic process, as I see it. So this is where I’d like to take what Nada Bakos, Manhunt, and Cindy Storer tell us, view it through the lens of Jeff Jonas’ insight, and see where else that leads us.

This to me is the crux of the thing.

For myself as a curious mind and game designer, what this boils down to is an investigation of the gameplay involved inp roblem solving, when the game-board extends from the virtual to the real, from thought to action, from the ideal to the practicable…

Indeed, our board also extends from our own models and games via the Great Game (in both its intel and Afghan meanings) to the deep game of life itself, of which Plotinus observed “Men directing their weapons against each other- under doom of death yet neatly lined up to fight as in the pyrrhic sword-dances of their sport- this is enough to tell us that all human intentions are but play…” — and not forgetting Keith Oatley‘s contemporary interpretation of the metaphor in his Shakespeare’s invention of theatre as simulation that runs on minds.

The gameplay of life, then — as is it practiced by the intelligence analyst, by the investigative journalist as Ms Bakos points out — by curious minds, as the phrase goes — and by game designers. Which last consideration is why I’d like to invite Mike Sellers, Brian Moriarty, and Amy Jo and/or Scott Kim and others to add their wisdom to the mix, should they happen to read this post…

**

Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) are the ones I think of most easily whose boards include both virtual and real spaces. Myths, beliefs and hard-nosed realities all impact both the Israeli-Palestinian issue and such games about it as PeaceMaker. The warfare in Mjolnir’s Game is deliciously asymmetrical. Three-dimensional chess has different “levels” to its boards, but no metaphysical distances between them — my own story-telling chess variant (see Playing a double Game) has both competitive and cooperative aspects tied in to every board move…

What other examples should we be thinking about? What other game design rules and heuristics might we apply?

The end game as Jonas describes it, happens quickly — in the context of a puzzle in which the “big picture” was complete for the designer before the pieces were scattered for play to commence, in which all the pieces in play are in fact part of the final picture, with none of them originating in other games and tossed randomly into the box, where none of the pieces are “false” in the sense of false flags, lies, propaganda, dissimulations, and so on.

Compared to the possibilities of deliberately deceptive pieces, duplicative pieces, partially obscured pieces and pieces of unrelated puzzles, the technical issue of pieces arising in different media is relatively easily handled by purely technical means (this I assume, having worked briefly with an early version of Starlight, correct me if I’m wrong).

And it is here — also an assumption of mine — that the analytic, pattern-recognizing mind will have the advantage over the machine.

**

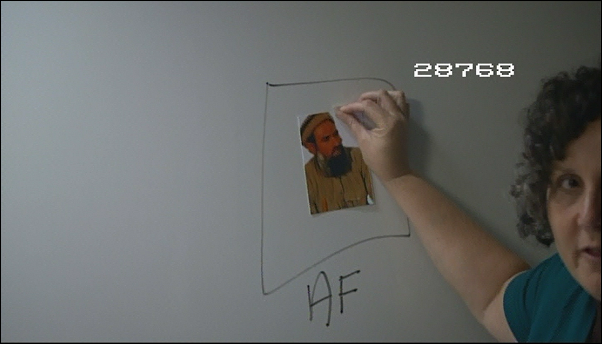

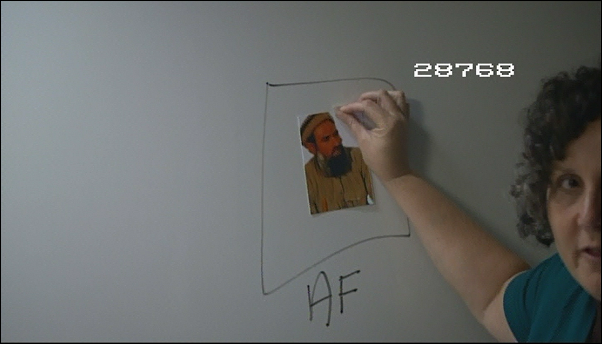

It’s the beginning of the game that interests me most — Jonas says that the moves are quickly made in the beginning, and in Manhunt there’s a moment where Cindy Storer pins the first puzzle piece — a photo of Abdullah Azzam, whose book The signs of Ar-Rahmaan in the Jihad of Afghanistan I’ve discussed before — into the first board space, which she’s labeled AF:

with the words:

Your starting point is Afghanistan. Abdullah Azzam is the Godfather of the Afghan jihad…

That’s a cinematic description of the process, of course, and there must have been a small flotilla of facts floating around in her brain — and the other brains working with her — at the time. Nevertheless, disciplined thought has to have a starting point, and Afghanistan, Azzam and the muj war against the Soviets offer the immediate context for the next face up and central focus of the pursuit, that of Osama bin Laden…

whose photo she pins up with the words “and his partner is Osama bin Laden…”

**

For additional context, here are some other quotes from Manhunt about the process:

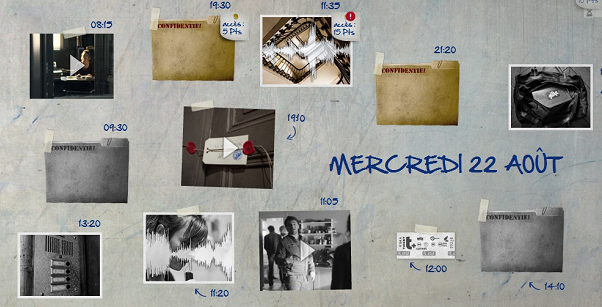

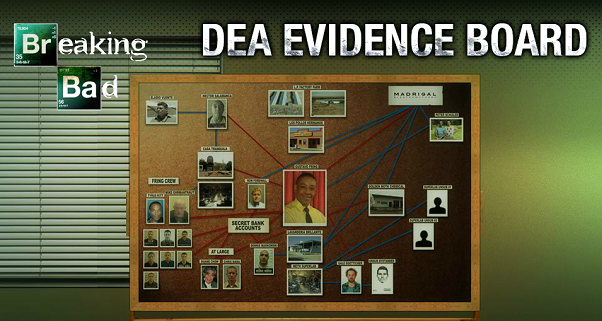

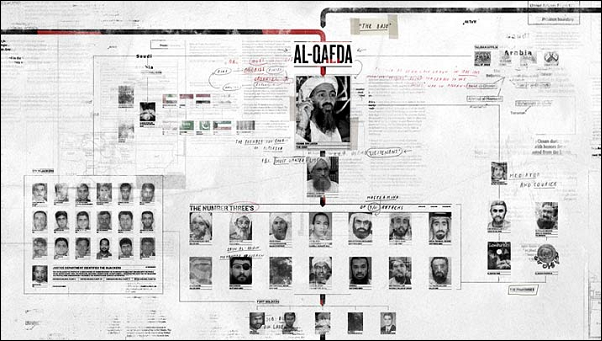

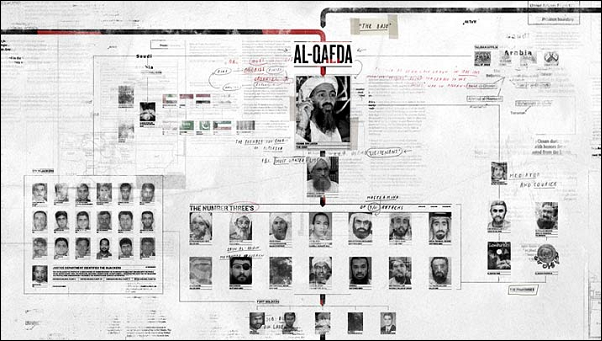

A link chart is the visual representation of a terrorist network and it’s what terrorism analysts spend much of their time building.

and:

My mental image is that, you know, I’m doing Jacob’s Ladder, you’ve got this string where you’re pulling the strings in your fingers, I feel like that’s what I feel I’m doing mentally.

and:

You know, trying to keep track of all the threads of various threats and which ones are real and which ones aren’t real and what connects to what. And, you know, people say, why didn’t you connect the dots? Well, because the whole page is black.

**

A sea of thoughts, then, in more than one mind yet strongly interconnected by whatever intel comes across the transom, conversations, memories, that needs to become physically represented in a way which represents links between the parties and their ideas, stated or surmised. With wild-cards, seepage, and needless duplication. Some oriented to materiel, some to morale: from munitions to Qur’anic meditations. A “semantic network“, with links as vertices, people and ideas as nodes (cf also “conceptual graphs“).

Something very like, in fact, Hermann Hesse‘s Glass Bead Game — only with a focus on threat, rather than conceptual elegance across the full range of human thought…

**

It’s a formidable task, then, moving first from copious scraps of intel to human minds that perform their own evaluative sorting. Here I’d invoke Coleridge‘s “hooks and eyes of memory” and suggest the process, like other forms of combinatorial insight, may require passionate examination, sub-conscious-threshold processing, and some reverie or rest time in which the unanticipated connection can be presented to consciousness… in a highly complex iterative process. And with each new connection or cluster of dots requiring is own drilling down for verification, and weighting adjustment so that salient masses and intriguing outliers are both held in steady remembrance…

— I think this whole process is what Ms Bakos was talking about when earlier she gave us the overall injunction, “you’re letting the information tell you what the picture is going to be” –_

And all this without the benefit of the “red and yellow thumbs” that Jonas talks about in jigsaw puzzles [ see interview here ], or more accurately, with the exact nature of the thumbs ranging from quantifiable links between telephones to near-stochastic leaps from a theological imperative to a tactic…

And with a board that doesn’t have the neat rectangular frame of a picture puzzle, where the frame is in fact the particular analyst’s account — a geographic area, a nation perhaps, or some other area of specific expertise. So there are no “easy corners” to find, just a buzz of data, a murmuration…

It’s magnificently hard. It’s epiphanic, it’s magical. Much of the magic takes place below the threshold of consciousness, but consciousness is not fond of admitting that. And Cindy Storer’s comments, to my ear, convey a whole lot of that magic without “capturing” it.

John Livingstone Lowes‘ The Road to Xanadu: A Study in the Ways of the Imagination, is I’m not mistaken, is a guided tour through the superb analytic puzzle piece and dot connecting mind o Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and a fir bed-time read for analysts. And I could go on, but this is long enough already.

**

My thanks to HBO, the crew and cast of Manhunt — and congratulations on the Emmy.

We’re at the beginning of an understanding of how the mind puts puzzle pieces together, connects dots, spots needles in haystacks, and in general recognizes patterns and irregularities, at this point– and there’s much more to be uncovered.

I recommend the Loopcast with Nada Bakos, and the series in general.

I recommend the Greg Barker / HBO documentary, Manhunt —

and you might also like to watch the fascinating mini-docu about the film’s title graphics

and read this comprehensive account of the titles

**

Filmcraft, like tradecraft, goes an order of magnitude above and beyond what is easily noticed to achieve its effect…

And damn, I still want time and attention to give that movie the close review it richly deserves!