Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism, book review

Saturday, October 5th, 2019[ By Charles Cameron — rise and fall, hubris and nemesis, a frequent pattern in human existence ]

.

Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche

by Mary Finnigan & Rob Hogendoorn

Jorvik Press, 199 pp. (2019)

The book benefits enormously from having twin authors — Rob Hogendoorn provides invaluable biographical and analytical material, credited to him as it occurs, while Mary Finnegan‘s contributions relate, in her own voice, her experiences. Both authors are Buddhist practitioners, both have researched the sexual abuse claims around Sogyal for years — claims which have since been admitted by Rigpa, Sogyal‘s teaching organization.

**

Mary Finnigan & Rob Hogendoorn‘s book title hits two human keynotes. You’ll find them intertwined for crowd-pleasing reasonsd in Game of Thrones:

It’s a question that’s been asked of Game of Thrones as long as the HBO series has been on the air: Why so much sex and violence?

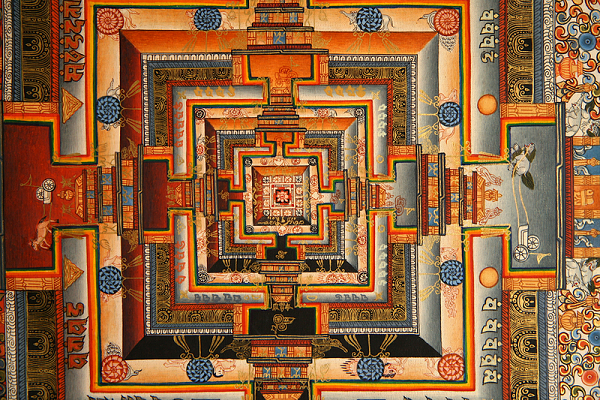

But Tibet? Perfect Tibet of our wishes? Tibet of the revered Dalai Lama? Tibet of the lamas who create intricate mandalas of colored sands — then brush them away in a gesture of impermanence and carry the dust to rivers which wash them out to sea? Shangri-La — in fact not fiction?

There’s a lot that’s wonderful to Tibetan Buddhism, and the better it looks and actually can be, the easier it is for non-Tibetans — us Westerners — to fall for the trap of projection — to believe, in this case, in the impeccability of Sogyal Lakar, sometimes titled Rinpoche, or Precious-One.

**

It’s unwise in general to speak ill of the recent dead, and Sogyal died in August 2019. Yet his story must be told, because unhappy though it is, the telling can help us avoid the illusion of a supposedly great lama — second only to the Dalai Lama in popularity in the west — who was in fact assaulting his female students sexually on numerous occasions across decades.

That’s the tale Mary Finnigan, herself a practitioner of Dzogchen — Sogyal‘s own form of Tibetan Buddhism — details in collaboration with her co-author Ron Hogendoorn in this book.

The accusations against Sogyal, of “sexual, physical and emotional abuse”, led to the Dalai Lama declaring Sogyal “disgraced”. The Charity Commission for England and Wales disqualified two of the Trustees of Sogyal’s organisation, the Rigpa Fellowship, in the UK because they covered up “knowledge of instances and allegations of improper acts and sexual and physical abuse against students”..

**

But although sex, violence, and sexual violence are at the heart of the anguish Sogyal inflicted on unwary students, there’s another side to Sogyal‘s story that Finnigan and Hogendoorn illuminate — the story of the son of a wealthy family, in contact with a senior Dzogchen lama and taken under his wing, who learned little that might have qualified him to be a teacher of that tradition, yet who managed to wangle his Tibetan nationality into the appearance of a gifted and highly educated lama on his arrival in England.

It’s a fascinating and heart-rending story — heart-rending is the word used by the New York Times in its obit for Sogyal — throwing light on Tibetan Buddhism itself, an astonishing mesh-work of visualizations and compassionate insight; the vicious politics that have long existed within the cloak of lamaism, and which the Dalai Lama has partially uncloaked; an archaic gender differential as power differential; and in general, eastern wisdom meets western credulity.

**

Sogyal‘s wealthy family connection gives him access to a high lama, Chokyi Lodro, and his presence at Lodro‘s side gives him in turn the title of Tulku, which often but not always signifies the reincarnation of some previous high lama, and is always a term of respect.

An authentically scholarly Tibetan meditation master, Dudjom Rinpoche, knows Sogyal has little to no education in the finer points of Tibetan philosophy or meditation, but considers him someone a western student might pick up some hints from — crossing the cultural divide as it were.

Sogyal , moving to the west, is on his way.

**

The years pass, just being a Tibetan guru in the west is sexy in the broad sense in which Lamborghinis and orchids are sexy: scholars of religion call it charisma. And when young and impressionable women become devotees of supposed high lamas — and when there are rumors, not without foundation, of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism including tantra, or spiritual-sexual practices, feelings and expectations can get very confused.

The main thrust of Mary and Rob’s book is to tell the rise and fall of Sogyal Lakar, his rise by that wider “sexy” quality we term charisma, his fall by discovery of the abuses of both spirituality and sex he’s inflicted on so many of his students across the years. I won’t go into the details, it’s their story to tell, and they tell it with the probing integrity of journalists as well as the sincerity of practitioners.

**

It has to be said that young Western women stood in line to sleep with Trungpa [“a formidably intelligent iconoclast” meditation master] and were usually eager to oblige with Sogyal. They became known as dharma groupies and sex with a Rinpoche became almost as much of a status symbol as plaster casting Mick Jagger.

Oh, Mary can write!

The problem was the abuse at Sogyal‘s “feudal” court.

**

The Heart Sutra of Mahayana Buddhism teaches something often translated:

form is emptiness, emptiness is form

where emptiness is better understood as <em>void, and void as devoid of self-establishing nature — so that these lines might be rendered:

Form is devoid of self-establishing nature,

absence of self-establishing nature is form,

**

Sogyal — no great meditation master, it would seem — has another form of emptiness. Whatever he may have thought, he lacked that compassion which is the fruit of deep meditative practice. And so he was able to enact violence on his students.

But we may witness that emptiness in another arena, that of scholarship.

Early on in Sogyal‘s time in the west, Dudjom Rinpoche is giving a talk to a hundred eager students, packed into a room intended for an average London family, and Sogyal is translating for him. Mary was there, sitting next to her then boyfriend John Driver, a linguist gifted in Tibetan, and noted that John was frowning. She writes:

During the first lunch break, John steered me into a cafe down the road. He was quite angry.

“Sogyal is not translating correctly,” he said. “Either he’s interpreting Rinpoche’s words into what he thinks is suitable for Westerners or he doesn’t understand what Dudjom is saying.”

**

It was a foreshadowing. Ever since Walter Evans-Wentz published an early English translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead in 1927, the gold-embossed green cloth volume has been a choice text to set beside the Chinese I Ching in pride of place on one’s desk or shelf. Come 1992, and The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying was published, updating the timeless Buddhist classic, personalizing it with some of Sogyal‘s own tales, made “accurate” to some degree by the inclusion of questions and answers from distinguished Tibetan masters such as Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and the Dalai Lama together with western masters of hospice living and dying such as Elizabeth Kubler-Ross — but, but–

As one student who was around at the time put it:

Could anyone who knew Sogyal imagine him being able to quote the German mystical poet Rainer Maria Rilke? Or the Sufi sage, Jalaluddin Rumi?

No, the “editor” who’d have provided those quotes, and much more of the content and form, indeed the very flowing language of the book, would have been Andrew Harvey, Oxford scholar extraordinaire and author of The Way of Passion: A Celebration of Rumi and other works.

So much for a great book — and it was and is great, and Sogyal deserves some, though by no means all, credit for it.

**

To sum up:

Sex and violence are paired in the book’s title. The problem with the sex is not that it was sex — Sogyal was no more a monk than Trungpa was, and it was often consensual. The problem was in the tirades, the humiliations, the violence, the abuse — delivered under cover of spiritual authority in violation of trust across a power and gender differential.

The scholarship is, well, Andrew Harvey‘s, and Padmasambhava‘s, and Kubler Ross‘.

**

I met Sogyal once. I asked him about the meaning of “skillful means”, and he responded “not entering or leaving a room through the wall, when there’s a door available.” He seemed pleasant enough. Trungpa Rinpoche I befriended at Oxford, and took to visit friends of mine at Prinknash Abbey near Gloucester: later he wrote that the visit had shown him the possibility of living the contemplative life in the west. He opened the first Tibetan monastery in the west shortly thereafter, Samye Ling in Scotland. And Mary is an old friend from hippie days.

As I indicated above, Mary and Rob have a story to tell, and they can tell a story.

Sogyal himself is no longer with us. He has entered, perhaps, the bardo, that liminal space between lives about which The Tibetan Book of the Dead — and to some extent its Sogyal reincarnation, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying — are written.

Go, read.