[ by Charles Cameron — capturing another item now vanished from its original URL ]

.

Aother repost of a web-page I occasionally want to link to, but which has disappeared into the mists, saved only by the Internet Archive, god bless ’em.

This second one comes from the Abu Muqawama blog, lately of CNAS, and features an interview Adam Elkus did with me — extremely handy when presenting my work to possible funders, publishers etc — thanks agan, Adam!

**

Interview: Charles Cameron

July 31, 2013 | Posted by aelkus – 3:15pm

Periodically, I’d like to give Abu M readers some exposure to interesting thinkers they may not otherwise read. I’m leading off the first interview with Charles Cameron. It’s hard to exactly summarize his interesting career. Though his work on religious thought and apocalypticism has the most relevance for Abu M readers, he also is a game designer and Herman Hesse aficianado. He specializes in rapid-fire blogged juxtapositions of interesting connections in the news, which you can read over at the Zenpundit archive. I was most interested in Cameron’s unique style of analysis, which may have utility to people interested in things like Design and applied creative thinking for security subjects.

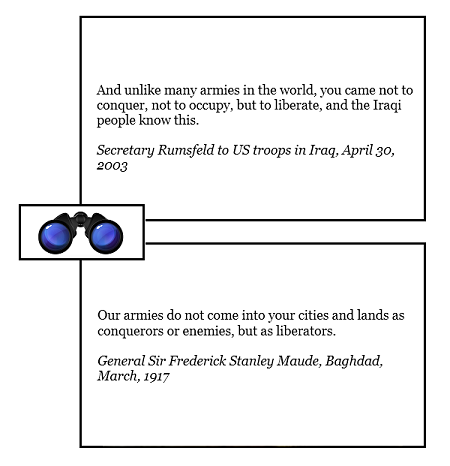

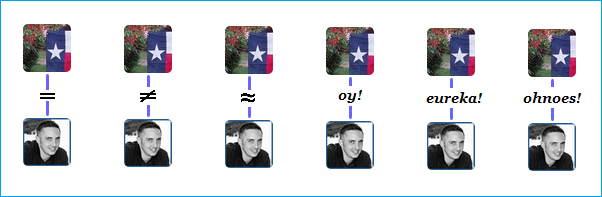

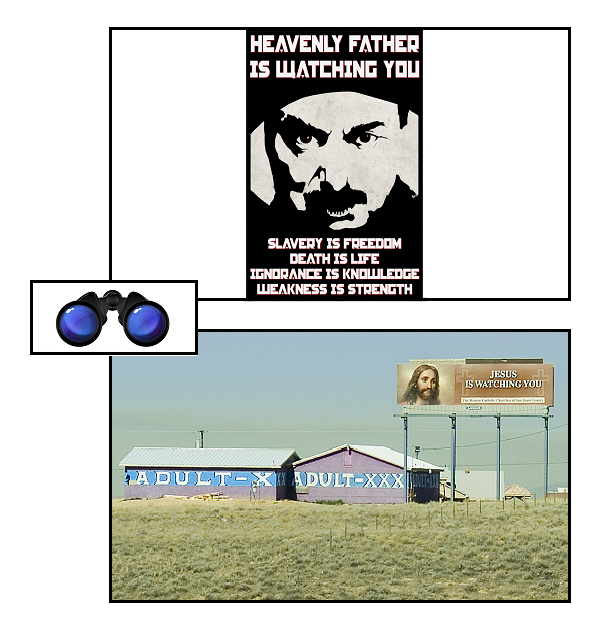

Adam Elkus: Your blogging is very reliant on pictorial juxtapositions and connections between disparate things. How did you come to this method, and what is it useful for?

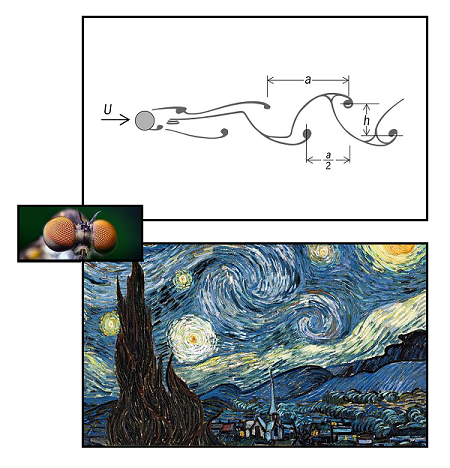

Charles Cameron: I think we’re moving pretty rapidly from an era of textual to a time of graphical thinking — and I’d tie that in to some extent with the arrival of cybernetics. Cause and effect can be represented by a straight line, cause effect and feedback needs to be a loop. So there’s a return to the visual and the diagrammatic, visible all over the place from sidebars in major news media to Forrester’s systems diagrams, the OODA loop, Social Network Analysis and PERT charts to Mark Lombardi’s paintings — that’s high science to mass media to museum-grade art. More generally, we see that the network rather than the line is the underlying form for everything from the internet to Big Data….And if you look back, you’ll see that all this picks up on themes we haven’t seen since the Renaissance.

Another way I see it is in terms of polyphony. If you want to model all the voices in a conflict, all the various stakeholders in a problematic situation, you need a notation, a way of representing their various tensions and interactions — a way to score their polyphony. And polyphonic & contrapuntal music is the closest analog we have — JS Bach is going to be the master here.

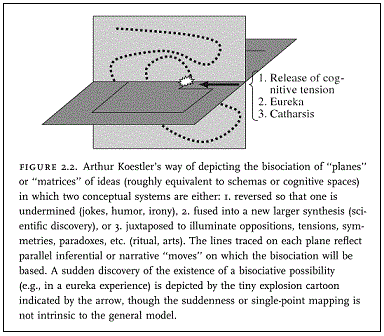

Creative insight, and indeed all thought, depends on analogy (Hofstadter; Fauconnier & Turner; Koestler) — so my Hipbone/Sembl Games and DoubleQuotes are designed to procure & explore creative/associative leaps & the fresh insights they bring, and nothing else. This is more a poet’s mode of thought than an engineer’s mode, & underused in heavily tech oriented analysis. The necessities of visual thinking also point me toward a humanly readable graph with “the magical number seven plus or minus two” nodes, with the nodes themselves not single data points but rich & complex ideas in compact form (nasheed, flag, logo, anecdote, video clip, quote), with multiple-strand, discipline- and silo-jumping juxtapositions between them.

Almost all of the above is prefigured in Hermann Hesse’s Nobel-winning novel, The Glass Bead Game, which has been my central intellectual inspiration for at least the last two decades.

AE: You study apocalyptic tropes in religious movements. Which vision of apocalypse do you find most disturbing?

CC: Well, first I should say that I’m not talking about the current pop-culture trope of nuclear-devastated landscapes and zombie invasions. I’m talking religious “end times” beliefs, aka eschatology, cross-culturally, and with specific attention to those with violent potential. Religion is often pigeonholed under politics, as though it’s just a veneer and everything can be satisfactorily explained without considering, eg, that it treats life after death as, if anything, a more powerful motivator than life before it — so we miss the turning point that “end times” thinking represents, with its implication that the current war is the final test on which you will be judged pass/fail by the One who created life, death and you yourself…

Broadly, I pay particularly note to unforeseen apocalypses, clashing apocalypses, and fictitious apocalypses. Muslim (Mahdist) apocalypticism was widely ignored because we knew so little about it, until well after 9/11 – yet the hadith saying the Mahdi’s victorious end times army with black banners will sweep from Khorasan (plausibly: Afghanistan) to Jerusalem has long been a major lure in AQ propaganda — while its correlate, the Ghazwa-e-Hind, is still largely dismissed. By clashing apocalypses I mean what happens when rival apocalypses mutually antagonize one another, as when the Mahdi is equated with Antichrist in Joel Richardson’s writings, or when Judaic, Christian and Islamic apocalypses clash over Israel and the Temple Mount — probably the driest tinder in the world right now, And by fictitious apocalypses, I mean the ones influentially but mistakenly portrayed in works of best-selling fiction such as the Left Behind series, or Joel Rosenberg’s far more engaging politico-religious novels.

AE: How has the study of apocalyptic tropes and culture changed (if it has at all) since 9/11 focused attention on radical Islamist movements?

CC: USC’s Stephen O’Leary was the first to study apocalyptic as rhetoric in his 1994 Arguing the Apocalypse, and joined BU’s Richard Landes in forming the (late, lamented) Center for Millennial Studies, which gave millennial scholars a platform to engage with one another. David Cook opened my eyes to Islamist messianism at CMS around 1998, and the publication of his two books (Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic, Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature), Tim Furnish’s Holiest Wars and J-P Filiu’s Apocalypse in Islam brought it to wider scholarly attention — while Landes’ own encyclopedic Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience gives a wide-angle view of the field in extraordinary detail.

I’d say we’ve gone from brushing off apocalyptic as a superstitious irrelevance to an awareness that apocalyptic features strongly in Islamist narratives, both Shia and Sunni, over the past decade, but still tend to underestimate its significance within contemporary movements within American Christianity. When Harold Camping proclaimed the end of the world in 2011, he spent circa $100 million worldwide on warning ads, and reports suggest that hundreds of Hmong tribespeople in Vietnam lost their lives in clashes with the police after moving en masse to a mountain to await the rapture. Apocalyptic movements can have significant impact — cf. the Taiping Rebellion in China, which left 20 million or so dead in its wake.

AE: What advice do you have for people looking to understand esoteric secular and religious movements relevant to national security and foreign policy?

CC: Since “feeling is first”, as ee cummings said, to “know your enemy” (Sun Tze) requires an act of empathy, the ability to feel how the enemy’s feelings must feel. That’s not an easy task for the rational secular mind, but to get a sense of the apocalyptic feelings of the jihadists, I’d recommend reading Abdullah Azzam’s Signs of the Merciful in Afghanistan, with its tales of miracle upon miracle, considering the impact of those narratives on pious but unlettered readers sympathetic to the idea of jihad…

Pay no attention to pundits. For real expertise, follow twitter and blogosphere, not Fox or CNN. Read widely. Read above your pay grade, see what the experts think are most significant distinctions. Look for similarities in own tradition and explore the differences — read Rushdoony on Christian Dominionism and C Peter Wagner on the New Apostolic Reformation to compare with the Islamist narrative.

Look for blind spots, and focus on them — they’re as important as the rear view mirror is when driving. Watch for undertows, movements in the making. Read comments sections, which will contain more unvarnished truth than is entirely comfortable. Notice where disciplines (or silos) intersect — learning which applies in two disciplines is at least twice as valuable as learning that only occurs in one. Read where worldviews collide. Lastly, I’d ask you to explore any tradition, whether you think it’s idiotic or not, until you know what’s most beautiful in it — so that, again, you see it with empathy & nuance, not just in black and white…