Perception and Strategy Part I.

Tuesday, March 20th, 2012

Jason Fritz at Inkspots had a thoughtful post about Afghanistan in light of recent events and made some points regarding strategy well worth further consideration. I suggest that you read his post in full, but I will comment on excerpts of his remarks below in a short series of posts. Here’s the first:

Delicate strategic balancing: perception’s role in formulating strategy

…..That all said, incidents in Afghanistan these past few months have caused me to question the validity of strategies that hinge upon the perspectives of foreign audiences*. This is not to negate the fact that foreign perspectives affect nearly every intervention in some way – there has been plenty of writing on this and believe it to be true. I firmly believe that reminding soldiers of this fact was possibly the only redeeming value of the counterinsurgency manual. To say nothing of this excellent work. But strategies that hinge upon the perspectives of foreign populations are another matter altogether.

I think Jason is correct to be cautious about either making perception the pivot of strategy or throwing it overboard altogether. The value of perception in strategy is likely to be relative to the “Ends” pursued and the geographic scale, situational variables and longitudinal frame with which the strategist must work. The more extreme, narrow and immediate the circumstances the more marginal the concern about perception. Being perceived favorably does not help if you are dead. Being hated for being the victor (survivor) of an existential war is an acceptable price to pay.

Most geopolitical scenarios involving force or coercion though, fall far short of Ludendorf’s total war or cases of apocalyptic genocide. Normally, (a Clausewitzian would say “always”) wars and other violent conflict consist of an actor using force to pursue an aim of policy that is more focused politically and limited than national or group survival; which means that the war or conflict occurs within and is balanced against a greater framework of diverse political and diplomatic concerns of varying importance. What is a good rule of thumb for incorporating perception into strategy?

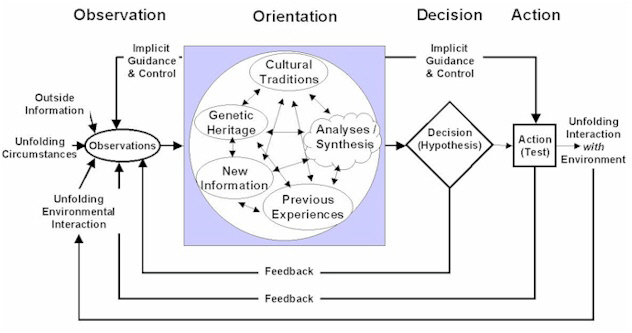

According to Dr. Chet Richards, the advice offered by John Boyd:

….Boyd suggested a three part approach:

- With respect to ourselves, live up to our ideals: eliminate those flaws in our system that create mistrust and discord while emphasizing those cultural traditions, experiences, and unfolding events that build-up harmony and trust. [That is, war is a time to fix these problems, not to delay or ignore them. As an open, democratic society, the United States should have enormous advantages in this area.]

- With respect to adversaries, we should publicize their harsh statements and threats to highlight that our survival is always at risk; reveal mismatches between the adversary’s professed ideals and how their government actually acts; and acquaint the adversary’s population with our philosophy and way of life to show that the mismatches of their government do not accord with any social value based on either the value and dignity of the individual or on the security and well being of society as a whole. [This is not just propaganda, but must be based on evidence that our population as well as those of the uncommitted and real/potential adversaries will find credible.]

- With respect to the uncommitted and potential adversaries, show that we respect their culture, bear them no harm, and will reward harmony with our cause, yet, demonstrate that we will not tolerate nor support those ideas and interactions that work against our culture and fitness to cope. [A “carrot and stick” approach. The “uncommitted” have the option to remain that way—so long as they do not aid our adversaries or break their isolation—and we hope that we can entice them to join our side. Note that we “demonstrate” the penalties for aiding the enemy, not just threaten them.]

I would observe that in public diplomacy, IO and demonstrations of force, the United States more often than not in the past decade, pursued actions in Afghanistan and Iraq that are exactly the opposite of what Boyd recommended. We alienated potential allies, regularly ignored enemy depredations of the most hideous character, debased our core values, crippled our analysis and decision-making with political correctness and lavishly rewarded treachery against us while abandoning those who sacrificed at great risk on our behalf . We are still doing these things.

Most of our efforts and expenditures at shaping perception seem to be designed by our officials to fool only themselves.

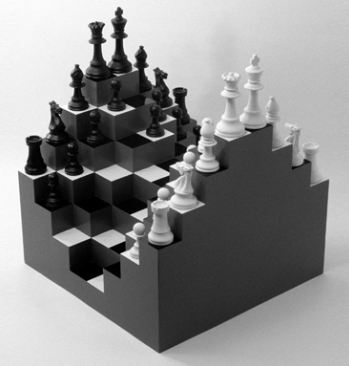

last actions, you are already onto your next ones. Get far enough ahead and the opponent’s decision making process will collapse and victory is assured.

last actions, you are already onto your next ones. Get far enough ahead and the opponent’s decision making process will collapse and victory is assured.