Recently, I finished two books on the iconic ancient Athenian philosopher Socrates, both of which pointed me to a third. The books were of a very different character and quality, yet together raised an important dichotomy about a man who lived 2400 years ago, whose intellectual legacy contributed to the shaping of Western civilization. The Stoics and Cynics looked back to Socrates as their forerunner; Socrates’ greatest student Plato became the most influential philosopher of the written word of all time, rivaled only by his own protege, Aristotle. So definitive was the influence of Socrates and his inexhaustible store of questions that all the Greek philosophers who came before him are reckoned “the pre-Socratics“. Yet he was put to death by the Democracy that had proudly boasted of being the “the school of Hellas“.

Who then, was the historical Socrates?

Socrates shares, to a lesser degree, the enigmatic quality of Buddha, Jesus and his own near contemporary, Confucius; we know more about Socrates than we do the others, but as with the others, it is all secondhand. Having written nothing himself, we must rely on the apologia of his disciples, the barbs of his critics, some statuary relics and the commentary of philosophers and historians from later in antiquity who had access to sources now lost to tell us of Socrates.

Here are the books:

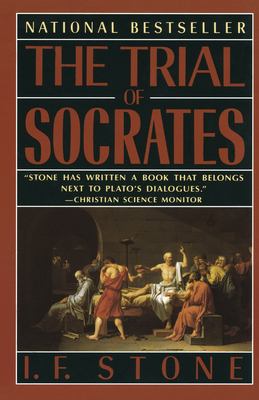

The Trial of Socrates by I.F. Stone

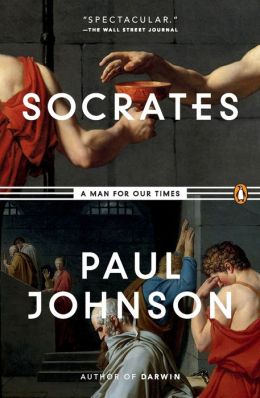

Socrates: A Man for Our Times by Paul Johnson

Both authors were splendid prose writers, otherwise they are a study in contrasts. The late I.F. Stone was a famous radical, an antifascist, an investigative, “muckraking” journalist of the mid twentieth century and, for a time, a Soviet agent during the “Red decade” of the Thirties. Stone, who was noted for his diligence with using government documents as a reporter, unearthing scoops everyone else had missed, became, in his retirement, a scholar of antiquity who read deeply in the classics in the original ancient Greek.

Paul Johnson began his career as a prolific writer and popular historian on the British Left with The New Statesman and over time shifted rightward to become a leading Anglo-Catholic conservative public intellectual, an adviser to Margaret Thatcher and an author of 40 books. Johnson is most known for his best-sellers that tackled panoramic and encompassing subjects – The Birth of the Modern, Intellectuals and The History of the Jews, often written from a highly idiosyncratic, as well as a conservative, perspective.

Of the two books, Stone’s The Trial of Socrates is by far the most substantive. Stone relies heavily, though not exclusively, upon primary sources in the original Greek to build his argument, which is that Socrates was executed because of his militant, arch-reactionary, “antipolitical” opposition to self-government, especially in the form of the Democracy; and further, that Socrates’ actions at his trial were perversely designed to inflame the jury which might easily have acquitted him. Socrates:A Man for our Times by Johnson is based on English translations of primary sources and secondary sources, is lighter in tone and much closer to being an essay. Johnson is evaluating the importance of Socrates in a broad, civilizational, context while Stone trying to tell what really happened while simultaneously judging Socrates culpability.

One point on which both authors have agreement is the mendacity and artistry with which Plato has made this task more difficult. I.F. Stone generally sees a “sneering” antidemocratic political continuity between Socrates and all of his disciples Plato, Xenophon, Charmides, Critias, Antisthenes and Alcibiades but even Stone cannot stomach Plato’s casual misuse (or abuse) of Socrates in his later dialogues to vent petty gripes and snobbish airs. Writing of an insulting passage in The Republic:

….Plato put this into the mouth of Socrates many years after the latter’s death. There is no evidence that the historical Socrates ever spoke so unkindly or pretentiously. Otherwise Socrates could not have had the lifelong affection of his oldest disciple, the “low-born” Antisthenes; his mother was a Thracian, hence he was twitted for not being of pure Attic blood (Diogenes Laertes, 6.1). Several scholars believe this was Plato’s slur against his fourth century rival – and Socrates’ old friend – Isocrates.[255]

Paul Johnson goes much further; attributing much that scholars regard as negative in Socrates’ reputation to the machinations of Plato using his late master as “a ventriloquist’s dummy”, a caricature Johnson calls “PlatSoc” to add authority to his own views and theories in which Socrates never believed or more likely, never even had heard:

….As an intellectual he [Plato] began to formulate his own ideas. As an academic he quickly merged them into a system. As a teacher he used Socrates to spread and perpetuate it. In his earlier writings Plato presented Socrates as a living breathing, thinking person, a real man. but as Plato’s ideas took shape, demanding propagation, poor Socrates whose actual death Plato had so lamented, was killed a second time, so that he became a mere wooden man, a ventriloquist’s doll, to voice not his own philosophy but Plato’s.

….So the act of transforming a living, historical thinker into a mindless, speaking doll – the murder and quasi-diabolical possession of a famous brain – became in Plato’s eyes a positive virtue. That is the only charitable way of describing one of the most unscrupulous acts in intellectual history. Thus Plato, with no doubt the best of intentions, created like Frankenstein, an artificial monster-philosopher [11]

There are other sources of information regarding Socrates than Plato, of course. Xenophon, also wrote an apologia; Aristophanes and other comic poets satirized Socrates in their plays, the philosopher being a “public figure” in Athens as much as was Pericles or Cleon (Socrates apparently could take a joke much better than the litigious and bloodthirsty demagogue Cleon); Aristotle had informed speculations regarding Socrates based on his long (and one suspects trying) tutelage under Plato and there are Roman writers such as Cicero who had access to sources now lost, but Plato remains the most prolific.

This is important, because the central thesis in The Trial of Socrates is that Socrates is not merely an “antidemocratic” gadfly in Athens, but an arch-reactionary teacher of “antipolitical” doctrines. That is to say that Stone argued that Socrates and his followers rejected the concept of the self-governing “polis” itself, oligarchy as much as democracy, that men were a “herd” fit only for a shepherd, an absolute Homeric ruler defined by Socrates as “the One who Knows”. Stone argues, with accuracy, that Socrates disciples, despite differences in personality and philosophy, shared a common disdain for democratic politics and furthermore, that Socrates teaching repeatedly led to cohorts of aristocratic, pro-Spartan,”Socratified youth” who twice supported the overthrow of the Democracy. In short that Socrates was tried because his activities, his “examinations”, were ultimately politically subversive to the state in a time of danger and instigated civil strife.

This means, to judge Stone’s argument requires that we discern Socrates from Plato that in turn requires some expertise on Plato. This need to sift Platonic dialogues explains why both Johnson and Stone, despite Stone’s ability to work with the primary texts in the original Greek, turned to the scholarship of Gregory Vlastos for guidance. Vlastos was a seminal figure in the field of Platonist philosophy whose work is described by other scholars as “transformative” and having “a vast influence” who best parsed Socrates from his artfully prolix disciple. Because of Stone and Johnson, I have picked up what is regarded by many as “the best book on Socrates” – Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher by Gregory Vlastos.

Vlastos, in this final book, ultimately came closer to Johnson’s position in the sense that some of what moderns find disagreeable in Socrates and what Stone criticizes in particular – the harsh antidemocratic edge – is more a product of Plato’s literary handiwork than the philosophy of the historical Socrates. Vlastos writes:

I have been speaking of a “Socrates” in Plato. There are two of them. In different segments of Plato’s corpus two philosophers bear that name. The individual remains the same. But in different sets of dialogues he pursues philosophies so different that they could not have been depicted as cohabitating in the same brain throughout unless it had been the brain of a schizophrenic

The early Socrates of the Elenctic Dialogues is the most genuine in the view of Vlastos.

End Part I.