[ by Charles Cameron — iconic images, riot police, compare and contrast, repetition with variation ]

First, let’s be clear that both these images have been widely considered iconic.

Thus NPR reported of the first photo:

There have been countless accounts of violence recorded during the uprisings in Egypt but the image that perhaps has captured the most attention is the most recent. The image has been widely referred to as the “girl in the blue bra.”

While Real Clear Politics quotes Michael Moore on the second:

“The images have resonated around the world in the same way that the lone man standing in front of the tanks at Tiananmen Square resonated. It is an iconic movement in Occupy Wall Street history,” Michael Moore declared on MSNBC’s “Last Word” program.

Moore was referring to police pepper spraying students at an “Occupy” protest at UC Davis.

So we have two similarities between the two images: they both show police in riot gear taking action against demonstrators, and they have both caught the public eye as somehow being representations that can “stand in” for the events they seek to portray.

Beyond that, it’s all compare and contrast territory — or variations on a theme, perhaps — and different people will find different reasons to attack or defend the demonstrators or the police in one, the other, or both cases.

1.

These are, for many of us, “home” and “away” incidents, to borrow from sports terminology, and some of our reactions may reflect our opinions in general of what’s going on in Egypt, or in the United States.

We may or may not know the rules of engagement in effect in either case, on either side.

In a way, then, what the photos tell us about those two events, in Tahrir Square and on the UC Davis campus, may tell us much about ourselves and our inclinations, too.

2.

As I’ve indicated before, I am very interested in the process of comparison and contrast that the juxtaposition of two images — or two quotes — seems to generate. And I’ve quoted my friend Cath Styles, too:

A general principle can be distilled from this. Perhaps: In the very moment we identify a similarity between two objects, we recognise their difference. In other words, the process of drawing two things together creates an equal opposite force that draws attention to their natural distance. So the act of seeking resemblance – consistency, or patterns – simultaneously renders visible the inconsistencies, the structures and textures of our social world. And the greater the conceptual distance between the two likened objects, the more interesting the likening – and the greater the understanding to be found.

I’d like to examine these two particular photographs, then, not as images of behaviors we approve or disapprove of, but as examples of juxtaposition, of similarity and difference — and see what we might learn from reading them in a “neutral” light.

3.

What I am really trying to see is whether we can use analogy — a very powerful mental tool — with something of the same rigor we customarily apply to questions of causality and proof, and thus turn it into a method of insight that draws on our aha! pattern recognition and analogy-finding intuitions, rather than the application of inductive and deductive reason.

And that requires that we should know more about how the mind perceives likenesses — a topic that is often obscured by our strong emotional responses — you’re making a false moral equivalence there! or look, one’s as bad as the oither, and it’s sheer hypocrisy to suggest otherwise!

So among other things, we’re up against the phenomenon I call “sibling pea rivalry” — where two things, places, institutions, whatever, that are about as similar as two peas in a pod, have intense antagonism between them, real or playful — Oxford and Cambridge, say, and I’m thinking here of the Boat Race, or West Point and Annapolis in the US, and the Army-Navy game.

Oxford is far more “like” Cambridge than it is “like” a mechanic’s wrench, more like Cambridge than it is a Volkswagen or even a high school, more like it even than Harvard, Yale, Princeton or Stanford — more like it than any of the so-called “redbrick universities” in the UK — so like it, in fact, that the term “Oxbridge” has been coined to refer to the two of them together, in contrast to any other schools or colleges.

And yet on the day of the Boat Race, feelings run high — and the two places couldn’t seem more different. Or let me put that another way — an individual might be ill-advised to walk into a pub overflowing with partisans of the “dark blue” of Oxford wearing the “light blue” of Cambridge, or vice versa. Not quite at the level of the Zetas and the Gulf Cartel, perhaps, but getting there…

4.

So one of the things I’ve thought a bunch about is the kind of analogy that says a : A :: b : B.

As in: Egyptian cop is to Egyptian protester as UC Davis cop is to UC Davis protester.

Which you may think is absolutely right — or cause for impeachment — or just plain old kufr!

And I’ve figured out that the reason people often have different “takes” on that kind of analogy — takes so different that they can get extremely steamed about it, and whistle like kettles and bubble over like pots — has to do with the perceptual phenomenon of parallax, whereby some distances get foreshortened in a way that others don’t.

5.

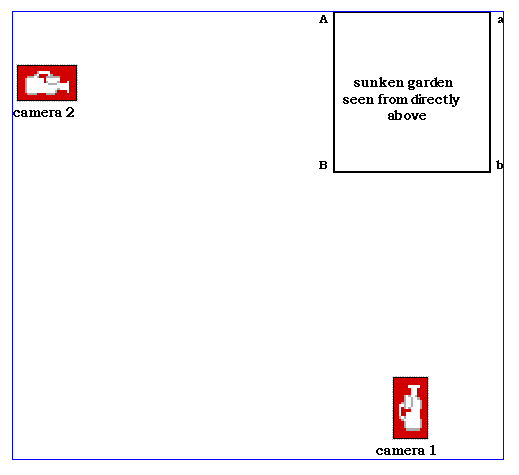

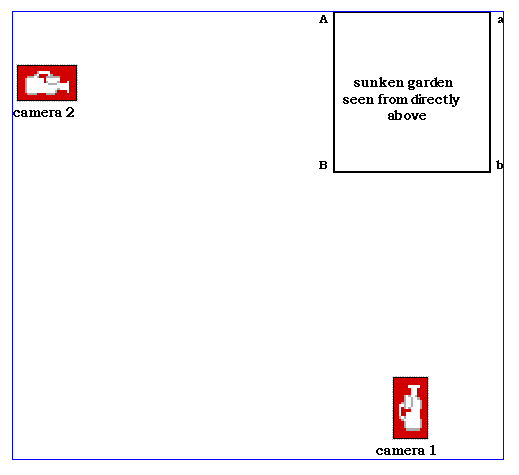

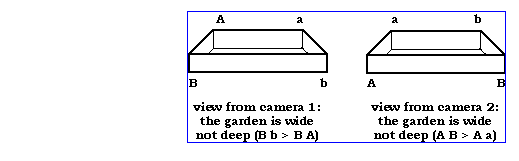

So my thought experiment sets up a sunken garden — always a pleasure, with two video cameras observing it, as in this diagram:

And from the two cameras, the respective views look like this:

In this scheme of things, Aa (Oxford) seems very close to Bb (Cambridge) seen from the viewpoint of camera 1 — but from camera 2’s standpoint, Aa (Oxford) and Bb (Cambridge) are at opposite ends of the garden, and simply couldn’t be father apart.

6.

Now, my thinking here is either so obvious and simple as to be a platitude verging on tautology — or one of those subtle places where the closer examination of what looks tautological and obvious leads to the emergence of a new insight, a new “difference that makes a difference” in Bateson’s classic phrase.

And clearly, I hope that the latter will prove to be the case here.

7.

What can we learn from juxtapositions? What can we learn from our agreements about specific juxtapositions — and what can we learn from our specific disagreements?

Because it’s my sense that samenesses and differences both jump out at us, as Cath Styles suggested — and that both have a part to play in understanding a given juxtaposition or proposed likeness.

Each juxtaposition will, in my view, suggest both a “sameness” and a “difference” — in much the same way that an arithmetic division of integers, a = qd + r, gives both quotient and dividend.

And then we have two or more observers of the juxtaposition, who may bring their own parallax to the situation, and have their own differences.

8.

Tahrir is to Tienanmen as Qutb is to Mao?

Or is pepper spray just a food additive?

And how do icons become iconic anyway? Are they always juxtapositions, cops against college kids, girl vs napalm, man against line of tanks? Even in the iconic photo of Kennedy from the Zapruder film, the sudden eruption of violence into the stateliness of a presidential parade is there — a morality play in miniature.

Any thoughts?