[ by Charles Cameron — this won’t be appearing in the Proceedings, sad to say — luckily, here at ZP I’m my own managing editor! ]

.

Bravely or foolishly, I keep on writing essays about our ignorance, in areas of which I’m ignorant myself. Not surprisingly, I don’t win any prizes, but I do manage to get my feelings about ignorance down and, sometimes, out.

For example, here’s my Coast Guard Essay Contest 2016 submission:

**

Of Boxes and Worldviews

What boxes may we imagine we’re in, as we consider this 2016 Coast Guard Essay Contest?

I ask this, because the challenge presented in the contest is described in part thus:

No issue is too big or too narrow as long as it makes the Coast Guard stronger. This does not mean authors cannot be critical and take on conventional wisdom and current practices. In fact, we encourage you to push the “dare factor.”

I’d argue that by now, it’s conventional wisdom to challenge conventional wisdom, that we’re now cosily settled in a box called “out of the box thinking” – that we’re effectively in “nested boxes” – and that what’s needed therefore is a grand scale questioning of the very way we think.

Is there such a thing as a Coast Guard question? There are certainly questions that have relevance to the US Coast Guard and its future, and some of them are mentioned in the prologue to this contest announcement – issues in the Arctic, which presumably range from sovereignty issues and under-ice flag raising claims, to the impact of methane release on global warming as permafrost melts in what amounts to a vicious circuit, a feedback loop, a serpent biting its own tail – issues of drug interdiction, to include the use of cartel submarines and drones, and so forth.

My problem with these questions is that they are effectively silos – specialty topics which, yes, the Coast Guard needs to address, and is indeed addressing, but silos, boxes nonetheless. In a word, they tend to the linear, in a world that is inherently cross-disciplinary, feedback-driven, complex – in which even the most straightforward of questions is involved with others in a peculiar web of tensions, arising and dissipating, between numerous vectors and stakeholders, of the sort first identified by Horst Rittel as “wicked problems”, and clarified thus by Dr Jeff Conklin of Cognexus:

A wicked problem is one for which each attempt to create a solution changes the understanding of the problem. Wicked problems cannot be solved in a traditional linear fashion, because the problem definition evolves as new possible solutions are considered and/or implemented.

Wicked problems always occur in a social context — the wickedness of the problem reflects the diversity among the stakeholders in the problem.

Most projects in organizations — and virtually all technology-related projects these days — are about wicked problems. Indeed, it is the social complexity of these problems, not their technical complexity, that overwhelms most current problem solving and project management approaches.

Importantly, Dr Conklin notes,

There are so many factors and conditions, all embedded in a dynamic social context, that no two wicked problems are alike, and the solutions to them will always be custom designed and fitted.

You don’t understand the problem until you have developed a solution. Indeed, there is no definitive statement of “The Problem.” The problem is ill-structured, an evolving set of interlocking issues and constraints.

This takes us way past the elegant, non-linear, feedback-aware models that Jay Forrester pioneered ar MIT under the name of Systems Dynamics, way past the simple rules-sets with which agent-based modeling works, and into a rarefied concept-space where the arts and humanities as much as tech and the sciences — perhaps even more – come into play.

Here the nature of the questions asked is neither disciplinary nor silo’d, the questions are not Coast Guard or Army, Intel or National Security, or even Medical or Aesthetic, Local or Global – but human: human questions, crossing not only the usual disciplinary boundaries, but the great Cartesian boundary between the physical and the spiritual – or as Clausewitz would say, between physical and moral.

It’s far easier to think in terms of men, women and materiel, all of which can be counted, than in terms of morale – which takes the women and men seriously, after all – because morale is far less easily quantified. Indeed, with the exception of Matrix Games, it is far easier to game the physical side of conflict than the human. And yet Clausewitz says,

One might say that the physical seem little more than the wooden hilt, while the moral factors are the precious metal, the real weapons, the finely honed blade.

I suggested above that we need to get out of the Matrioshka-nested boxes of our current thinking, and if I can put that another way, we need to get to the heart of creativity.

**

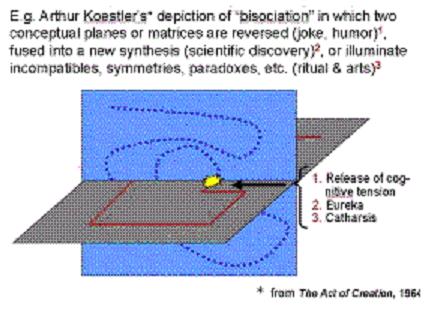

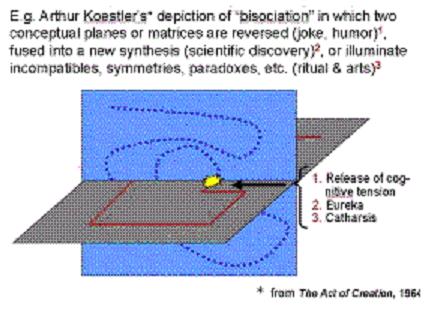

From the point of view of pure creativity, as diagnosed by Arthur Koestler in his classic book, The Act of Creation, the aha! or eureka! of the creative breakthrough is in fact a “creative leap” — from one frame of reference to another, as shown in this diagram based on those in his book:

From the point of view of cognitive science, as Gilles Fauconnier & Mark Turner illustrate and confirm with neuro-scientific precision in their book on “conceptual blending”, The Way We Think, the tide has now turned from a more literal to a more analogical understanding of mental processing, at the most basic levels, and across all disciplines:

We will focus especially on the nature of integration, and we will see it at work as a basic mental operation in language, art, action, planning, reason, choice, judgment, decision, humor, mathematics, science, magic and ritual, and the simplest mental events in everyday life. Because conceptual integration presents so many different appearances in different domains, its unity as a general capacity had been missed. Now, however, the new disposition of cognitive scientists to find connections across fields has revived interest in the basic mental powers underlying dramatically different products in different walks of life.

From the point of view of Marshall McLuhan, writing to the poet Ezra Pound back in the 1940s, the issue is that following the rational enlightenment of the eighteenth century, which brought us today’s scientific and technological breakthroughs but has left us a wasteland in terms of values, threatening our planetary home with our weapons, our eager overpopulation, our fierce tribalisms, and excessive energy requirements, we have lost one central ingredient in human thought: the ability to think analogically rather than logically, in terms of relationships rather than linear causality.

McLuhan wrote, presciently,

The American mind is not even close to being amenable to the ideogram principle as yet. The reason is simply this. America is 100% 18th Century. The 18th century had chucked out the principle of metaphor and analogy.

And computer scientist and Pulitzer prize-winner Douglas Hofstadter has aptly subtitled his book Surfaces and Essences, co-authored with cognitive scientist Emmanuel Sander, “Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking”.

The analogical leap is the leap out of the box.

**

Thus far I’ve de-emphasized the “Coast Guardness” of my thinking. But let’s view some Coast Guard related issues in light of the above:

Let’s take a simple lateral comparison first – how does the Chinese Coast Guard compare with our own, what are the physical overlaps and differences, strengths and weaknesses, of theirs and ours?

Please note that this question cross-cuts, to a greater or lesser degree, with any and all other questions involving the USCG. It also leaps from ours to theirs, responds to Sun Tzu’s “know your enemy”, works by comparison and contrast, invites us into detail – and is far more easily answered in physical terms than in terms of morale. SIGINT is better at locating ships than at reading the mind and heart.

Budgeting.

If ever there was a tangled knot, the US system for allocating budgetary items would be it. Not only do the federal services each have a series of individual pulls and pushes, but the fifty states, their senators and congresspeople do too. And then there’s the lame-duck president and the president soon to be elect. Until November, there’s the two party scramble, with voters on both sides of the aisle drifting to and fro between partisanship, frustration, and independence. And there are undertows and swells of popular emotion influencing these other factors.

The Coast Guard, arriving at its wish list for the next budget, must be single minded as to its objectives, flexible as to its willingness to negotiate – to a point – but balancing its clearly understood urgencies against the shifting tides of political wills in concert and in conflict, in a multi-vectorial tug-o-war, one against many. And there are no doubt similar tussles within the USCG, doctrinal purists and innovators, old hands and new, with their own mixed agendas, their temporary victories and defeats.

Humans, wily at times, straightforward at others, subject to shame and pride – the conceptual landscape within which any particular problem plays out – let alone the interlocking monster of the whole – is inevitably subject to constant change, closer to the paradoxical understanding of Heraclitus that all is flux than to Coast Guard Office of Strategic Analysis doctrine. Hey – it may well be that the Coast Guard would by its nature have understood the threat-nature of the Iranians in Millennium Challenge 2002 as well as Paul Riper, playing red team, did. From USCG to Marines is a difference of silo, but cross-fertilization is the name of the next game, and Defense Readiness (CG 3-0, Operations, 2.2.4) 1., Maritime interception/interdiction operations, is an area of USCG theoretical expertise and practical experience.

In short, the move is from blocked out and simplified complexity to a far more richly complex way of thinking, analogous to an n-dimensional concept space of shifting weights and tensions, of which this water-loaded spider’s web is a pretty good two-dimensional analog:

Imagine each water drop is a player, and that the entire web reconfigures as one drop shifts or is shaken, caroming into another, perhaps stretching one of the strands of the web past breaking point – and all this in an n-dimensional space beyond the capacity of most human minds to cognize, let along predict.

It is this kind of web into which our massive data inflows are directed, and the interface between the data-crunching capacity of our computers and analytic software, and the multiplex capabilities of the keenest human analytic minds – that’s where the “intel” usefully functions. Before it hits that interface is is data. Within a capable mind, or within the web-like tensions and resolutions of our keenest domain expert, analytic, and hopefully decision-making minds, is where the intelligence becomes meaningful.

Incalculable data points, multitudinous conflicting interests, and the human instinct for meaning.

As the US Coast Guard’s European colleagues have been finding out under increasing public scrutiny and with painful intensity, not only are there political and scientific issues to navigate, there can also be strictly humanitarian impacts of the sort that we find occurring in the interdiction of refugee boats making the trip between Turkey and the Greek island of Chios.

All in all, the work of the Coast Guard is a potent brew, and Computer Go pales before its complexity.

**

On a more personal note..

Do you speak any form of Inuit? Or Athanbaskan? There are in fact 16 indigenous languages with corresponding worldviews in Alaska.

What are caribou to you? Are you fluent in the magical worldview of the shamans? And what, as climate change drastically reshapes native Alaskan living, takes the place of shamanism in the leadership of native populations – in Alaska, an area of special concern to the USCG?

If you are of a scientific bent – and the USCG Academy awards Bachelor of Science degrees, so most who have passed through those gates into the Service probably are – how concerned are you by global warming – and how concerned by comparison with the preservation of Inuit or Athabaskan culture?

The truth is that both go together.

Military and law enforcement agencies are tasked with setting things right in the external world, but the world of the human psyche has its own specialists – psychiatrists no less than spiritual leaders – and while at some level the US Presidency is often considered the pinnacle of human power, there’s also a category of figures we respect for a different kind of authority, one that is earned above all by integrity and generosity of spirit: the names of Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, Mahatma Gandhi and Pope Francis come to mind.

Each of these four figures embodies the practice of contemplation in action – a practice which looks within the self for a compassionate response to adversity. Among the Inuit, and across the circumpolar region more generally, this practice of looking inward for values is the particular task of the shaman – and more recently, the artist.

The Yupik, Inupiaq and Irish artist Susie Silook’s work, Looking Inside Myself, is a recent sculptural presentation of this theme:

Cultural anthropology thus opens us to entire worldviews which are themselves both important to local stakeholders and profoundly illuminating in their own right. Indeed, in these worldviews, the whales, walrus, seals, the ravens and reindeer have voices – a concept largely foreign to western thinking until Mr Justice Douglas gave his dissenting opinion in SIERRA CLUB v. MORTON, 405 U.S. 727 (1972), alerting the nation via the Supreme Court that ecological considerations could no longer be ignored in coming to terms with the world we live in. In the arctic, such considerations have peculiar force, by reason of the extreme nature of the human and natural habitat.

An anthropologist such as Richard Nelson can live in the style that anthropologists term “participant observation” with peoples of very different cultural assumptions than our own for extended periods, and with no other motive than to understand their host cultures — and thus gain both the people’s trust and a depth of insight into their understanding of the world — of which Nelson’s Make Prayers to the Raven, in which he presents an Athabaskan view of the natural world, is a celebrated example. The study of the circumpolar bear cult, as presented by Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders in their The Sacred Paw: the Bear in Nature, Myth and Literature, arguably brings us as close to the archaic origins of religion as human science can bring us.

Somehow, these matters of extreme subtlety must at times be borne in mind while making the split-second decisions so characteristic of both military and law enforcement practice. And the higher the decision-maker in an action-oriented profession, the greater the need for deep understanding. In Napoleon’s own words, we can see that his actions, too, sprang from contemplation:

It is not genius which reveals to me suddenly and secretly what I should do in circumstances unexpected by others; it is thought and meditation.

Thought and meditation are the activities that prepare the mind for what Clausewitz termed the coup d’oeil:

When all is said and done, it really is the commander’s coup d’œil, his ability to see things simply, to identify the whole business of war completely with himself, that is the essence of good generalship. Only if the mind works in this comprehensive fashion can it achieve the freedom it needs to dominate events and not be dominated by them.

I have emphasized the cultural and contemplative side of things because Clausewitz’ “comprehensive” fashion of thinking demands it. The USCG Arctic Strategy mentions cultural matters only very briefly, giving far more weight to ecological considerations – which while complex in their own right, and sadly contested in the case of global warming, are far easier for a contemporary western, scientifically-trained mind to comprehend than the diverse human value systems of other cultures.

Indeed, from an Alaskan native perspective, climate change and the tradition values of the peoples are tightly coupled at the leadership level. From a native perspective, there is a need for a new kind of leadership, one that replaces traditional shamanism, well-adapted to earlier conditions but now lost, with an exacting blend of traditional and modern forms of knowledge. As Steven Becker puts it in “A Changing Sense of Place: Climate and Native Well Being”, in face of an uncertain future, “agile and adaptive leaders” are required, who “can meet the physical, economic, and sociocultural challenges resulting from climate change.”

These leaders need to be well versed in western science and management, but they must also be thoroughly grounded in their Native language, culture, and traditions (Kawagley 2008). They must see the value in both Native and western science, see the complementary uses of the two, and use both methods appropriately as the basis of true adaptive management (Tano 2006).

I have emphasized this “new shamanic leadership” issue, not because interactions with native leaders will occupy more USGC time and attention than air-sea rescues or other highly visible, courageous and newsworthy exploits but precisely because they are subtle, not likely to capture headlines, and thus easily overlooked – and also because they touch on my own personal interests.

But not only are these “agile leaders” (or “new shamans” as I prefer to think of them) leaders with whom forward-thinking Alaska-based USCG members may on occasion fruitfully collaborate, but because they are also emblematic of leadership in general, embodying both the best of scientific and technological “hands on” know-how with the finest human and ecological values.

In this, they represent the way forward, not just for the Coast Guard or Alaska, but for contemporary civilization in a world of rapid, complex, often dangerous, and ultimately transformative change.

**

Well, whaddaya think, eh?