Infinity Journal: Can Grand Strategy be Mastered?

Tuesday, July 25th, 2017[Mark Safranski / “zen“]

The new edition of Infinity Journal is out and they have a most interesting article by Dr. Lukas Milevski, a promising young scholar best known for his recent book The Evolution of Modern Grand Strategic Thought.

Can Grand Strategy be Mastered?

….The first conceptualization of grand strategy, broadening the concept to include all instruments of national power and not simply the military, may arguably be quite useful. Policy-makers and strategists all should understand how military power fits in with non-military power, and vice versa, to achieve desired effects. They must understand the assumptions which implicitly underpin each form of power and how they integrate and contradict among themselves. As Lawrence Freedman argued in 1992, “[t]he view that strategy is bound up with the role of force in international life must be qualified, because if force is but one form of power then strategy must address the relationship between this form and others, including authority.”[ix]

The use of non-military power against an adversary in war is clearly not simple diplomacy, but also is not encompassed within classical definitions of strategy. Grand strategy may or may not be an appropriate term for it; in recent decades the British have labeled it the comprehensive approach. Yet, given how many authors have paid lip service to the variety of forms of power inherent in this interpretation of grand strategy, the amount of attention actually dedicated to the non-military forms of power has been startlingly low. As Everett Carl Dolman suggested in a somewhat blasé manner, “[a] worthy grand strategist will consider all pertinent means individually and in concert to achieve the continuing health and advantage of the state.”[x] Yet one may reasonably ask, ‘but how?’ To make connections among categories and among distinct fields and disciplines is one of the primary purposes of theory, yet this has simply not been done in the grand strategic literature even when this task is implicit and inherent in the definition of the concept itself.[xi] Furthermore, without the achievement of this difficult scholarly work, grand strategic theory which adheres to this form of the concept will never fulfill Clausewitz’s appreciation of theory.

….In principle, grand strategy, conceived along the lines of incorporating multiple instruments beyond the military, can indeed be mastered. However, there is no theory yet which may guide those who desire to master grand strategy in this manner. Practice in the world of action may, of course, still take place without theory—or at least academic theory. Yet without proper guidance, chaos among the various military and non-military instruments is inevitable. They will not work properly together; they may even achieve contradictory effects; and so forth. The comprehensive approach, as practiced in Afghanistan and Iraq, has not been particularly successful.

The second conceptualization of grand strategy, as being placed above policy in a hierarchy of ideas and duties, along with the subsidiary characteristic of enduring over lengthy periods of time, is less transferable to the world of action. Each aspect of this second understanding of grand strategy contributes individually to limiting the transferability of the concept.

Read the whole thing here.

Milevski is a grand strategy skeptic and as such he raises fair questions in his article regarding grand strategy as an actionable thing that some enterprising official, politician or military officer could master. Though he does not raise it explicitly, Milevski’s argument reflects a longstanding debate on whether grand strategy is even a thing one can do or is merely a retrospective historical explanation. Aiding Milevski is that while there has been much learned commentary on grand strategy by eminent scholars or practitioners like Kennan and Kissinger, conceptually it is a muddle with competing definitions and lacking a coherent accepted theory. Much like obscenity, we seem to know grand strategy when we see it (Containment! Bismarck!) but can’t really explain why it happened here and not there.

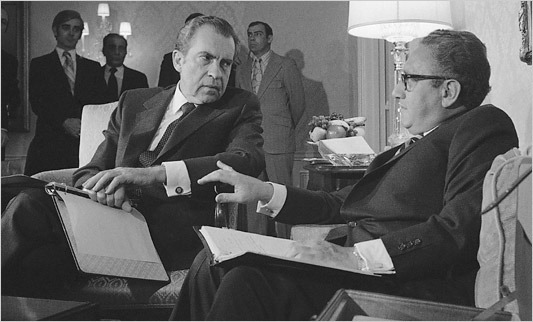

The two competing definitions Milevski raises complement one another but they are not the same. The first is what is sometimes in America called a whole-of-government approach to conflict and Milevski admits this version of grand strategy is one that could potentially be mastered, albeit there is no pathway to do so. The reason for this is that is that grand strategy requires a fairly robust centralization of political power to be realized. To do grand strategy, it helps if you are Otto von Bismarck, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, Pericles, Peter the Great or some similar figure. Middle level bureaucrats in democratic polities might conceive or suggest grand strategies but unless they convincingly sell their idea to the ruling elite and then the elite to the public (Dean Acheson, for example, “scaring the hell out of the country”) it won’t become actionable policies, diplomatic agreements or military operations. This is possible but rarely happens without an existential strategic threat or at least the perception of a serious one.

Milevski is less enchanted, as are Clausewitzians generally, with the second version of grand strategy that posits a great idea or theme floating above policy, guiding it over very long periods of time such as decades or centuries. Objectively, it is hard to come up with a rationale why this could not be happening more often because it doesn’t though we can point to examples where nations or empires have followed a principle consistently in peace or war for a very long period of time; for example, Britain seeking to prevent any power from dominating continental Europe or China’s tributary system for managing dangerous barbarian tribes and neighboring states. Subjectively, Clausewitzians simply don’t like “grand strategy” violating the hierarchy Clausewitz set forth to explain the relationship between politics/politik, policy and strategy in war. Milevski spends time on this objection specifically.

I’m less troubled by the contradiction than Dr. Milevski, though it’s worth considering that in theory the two different versions of grand strategy could be different phenomena instead of competing definitions of one. Much of the first version of grand strategy could also be termed “statecraft” and the second is something like John Boyd’s theme of vitality and growth or at a minimum, an aspirational security paradigm. It’s more of a vision or an opportunistic operating principle than a well honed strategy or clearly defined end-state. It is open-ended to permit maximum political flexibility and accommodate many, at times competing, policies. The second version of grand strategy is not at all strategy in the sense applied to a theater of combat for concrete objectives; it is more political, more gestalt.