[ by Charles Cameron — Iran, unknown unknowns, Madhyamika philosophy and a blessed unknowing ]

.

.

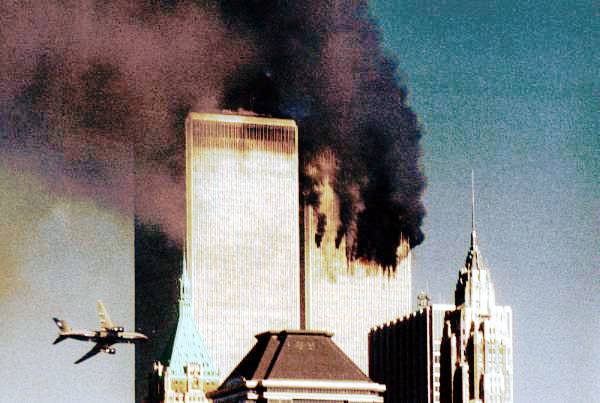

image from Jackson Pollock / AustinKids—

an artist’s representation of a wicked problem to be untangled?

1.

Dr. TX Hammes, who will need no introduction to most ZP readers, wrote a few days back in On Bombing Iran, A False Choice:

While there has been some discussion of Iran closing the Straits of Hormuz, there has been no consideration of other Iranian actions – mining harbors overseas (using merchant ships), major attacks on oil production chokepoints globally or major terror attacks using the nuclear equivalent explosive power inherent in many industrial practices. In short, bombing proponents assume Iran will be an essentially supine enemy and not attempt to expand the conflict geographically or chronographically.

Iran is a classic wicked problem. Any “solution” brings a new set of problems. Lacking a solution, the strategist’s job is to think through how to manage such a problem.

My train of thought now departing the National Defense University on Dr Hammes’ platform will make its way with stops at Hans Morgenthau, Jeff Conklin and Richard Feynman to a final destination deep in the heartland of Buddhist Madhyamika philosophy with Elizabeth Mattis-Namgyel.

2.

Drs. Francis J. Gavin and James B. Steinberg‘s recent Foreign Policy piece The Unknown Unknowns carried the subtitle:

If the past half-century of American political history has taught us anything, it’s that we can’t possibly know the consequences of bombing — or not bombing — Iran

and opined:

Based on our experiences — one of us a former senior policymaker, the other a historian of U.S. foreign policy — we are convinced that the “right” answer, but the one you will never read on blogs or hear on any cable news network, is that we simply cannot know ahead of time, with any degree of certainty, what the optimal policy will turn out to be. Why? Even if forecasters could provide probabilities about the likelihood of a narrow, specific event, it is simply beyond the capacity of human foresight to make confident predictions about the short- and long-term global consequences of a military strike against Iran.

3.

It appears that this sense of unknowing has application beyond the specific question of whether or not to bomb Iran. Blog-friend Peter J Munson just the other day quoted Hans Morgenthau in a short SWJ piece titled Gentile: Realities of a Syrian Intervention — using a Morgenthau quote that he also features as an epigraph to his book, Iraq in Transition: The Legacy of Dictatorship and the Prospects for Democracy.

So that’s Iran, Iraq and Syria — but the Morgenthau quote itself, from his Politics among Nations, is even more general in application:

The first lesson the student of international politics must learn and never forget is that the complexities of international affairs make simple solutions and trustworthy prophecies impossible.

Okay?

4.

And it goes further. Love that quote from Laurence J Peters that Jeff Conklin uses as the epigraph to his seminal paper on Wicked Problems:

Some problems are so complex that you have to be highly intelligent and well informed just to be undecided about them

Next up, here’s the Nobel physicist Richard Feynman speaking in The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, a Horizon / Nova interview, illustrating the approach Morgenthau takes to international relations as applicable to the grand issues of philosophy, religion and science:

I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong. I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of certainty about different things, but I’m not absolutely sure of anything and there are many things I don’t know anything about, such as whether it means anything to ask why we’re here, and what the question might mean.

5.

And how far is that from Elizabeth Mattis-Namgyel, student and wife of the lama Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, writing in her book on Madhyamika, The Power of an Open Question (p. 58):

Maybe experiencing complexity brings us closer to reality than does thinking we’ve actually figured things out. False certainty doesn’t finalize anything. Things keep moving and changing. They are influenced by countless variables, twists and turns … never for a moment settling into thingness. So maybe we should question the accuracy or limitations of this kind of false certainty. Conflicting information confuses us only when we’re trying to reach a definite conclusion. But if we’re not trying to reach a conclusion in the first place — if we just observe and pay attention — we may actually have a fuller, more accurate reading of whatever we encounter.

6.

Zen, too, welcomes this “open ended” approach in its working with koans, those mysterious and / or paradoxical riddles and / or poetic statements and / or legal cases for which such teachers as Dogen Zenji had such affection. In the words of Shozan Jack Haubner:

The searching, open-ended nature of koan work yields the kind of answer, however, that frustrates easy analysis, not to mention that most exquisite of all human pleasures: being “right.” For, ultimately, koan practice teaches that as long as a question is alive in the world around us, it should not — indeed, cannot — be settled once and for all within us. Koan practice does not put life’s deepest issues “to bed.” It wakes these issues up within us, waking us up in the process.

or consider this, from Lin Jensen, An Ear to the Ground: Uncovering the living source of Zen ethics:

Judgments on right and wrong are a nearly irresistible enticement to pick sides. And that’s exactly why the old Zen masters warned against becoming a person of right and wrong. It isn’t that the masters were indifferent to questions of ethics, but for them ethical conduct went beyond simply taking the prescribed right side. For these masters, the source of ethical conduct is found in the way things are, circumstance itself: unfiltered immediate reality reveals what is needed.

Policy-makers, of course, can’t suspend judgment indefinitely — but maybe a contemplative approach in general would make them better prepared for snap judgments and sound intuitions when such are called for. Clausewitz [grinning, with an h/t to Zen here]:

When all is said and done, it really is the commander’s coup d’œil, his ability to see things simply, to identify the whole business of war completely with himself, that is the essence of good generalship. Only if the mind works in this comprehensive fashion can it achieve the freedom it needs to dominate events and not be dominated by them.

7.

And let’s go the distance…

Here’s Elizabeth Mattis-Namgyel again, from an online retreat she gave last year for subscribers to Tricycle magazine:

We need to ask, what is love or beauty or pain before we objectify it? what happens when we can abide without conclusions? you know, these are questions for the practitioner, practitioners questions… and I wanted to use one word in Tibetan that I’ve found very useful for myself… and this is the word zöpa.. this translates usually as patience or endurance or tolerance, but there’s this very subtle translation of zöpa, which is the ability to tolerate emptiness basically, which is another ways of saying the ability to tolerate that things don’t exist in one way, that things are so full and infinite and leave you so speechless, and so undefinably grand – and these are just descriptive words, but you have to use some words to communicate, I guess — the ability to bear that, that fullness, like we’ve been talking about, not turning away, not turning away.