Moral Decay and Civilizational Rebirth

Wednesday, October 13th, 2010

John Robb at Global Guerrillas:

Moral decay is often cited as a reason for why empires/civilizations collapse. The slow failure of the US mortgage market, the largest debt market in the world and the shining jewel of the US economic/financial system, is a good example of moral decay at work.

Why is this market failing? It’s being gutted — from wholesale fraud and ruthless profiteering at the bank/servicer level to strategic defaults at the homeowner level — because a relatively efficient and effective moral system is being replaced by a burdensome and ineffective one. What shift? Our previous moral system featured trust, loyalty, reputation, responsibility, belief, fairness, etc. While these features were sometimes in short supply, on the whole it provided us with an underlying and nearly costless structure to our social and economic interactions.

Our new moral system is that of the dominant global marketplace. This new system emphasizes transactional, short-term interactions rather than long-term relationships. All interactions are intensely legalistic, as in: nothing is assumed except what is spelled out in the contract. Goodness is solely based on transactional success and therefore anything goes, as long as you don’t get punished for it.

In this moral system, every social and economic interaction becomes increasingly costly due to a need to contractually defend yourself against cheating, fraud, and theft. Worse, when legalistic punishment is absent/lax, rampant looting and fraud occurs.

Given the costs and dangers of moral decay, it’s not hard to see why it can cause a complex empire/civilization to collapse.

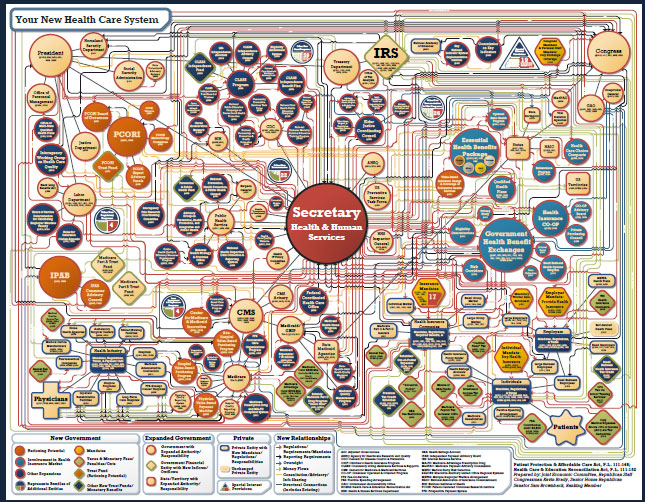

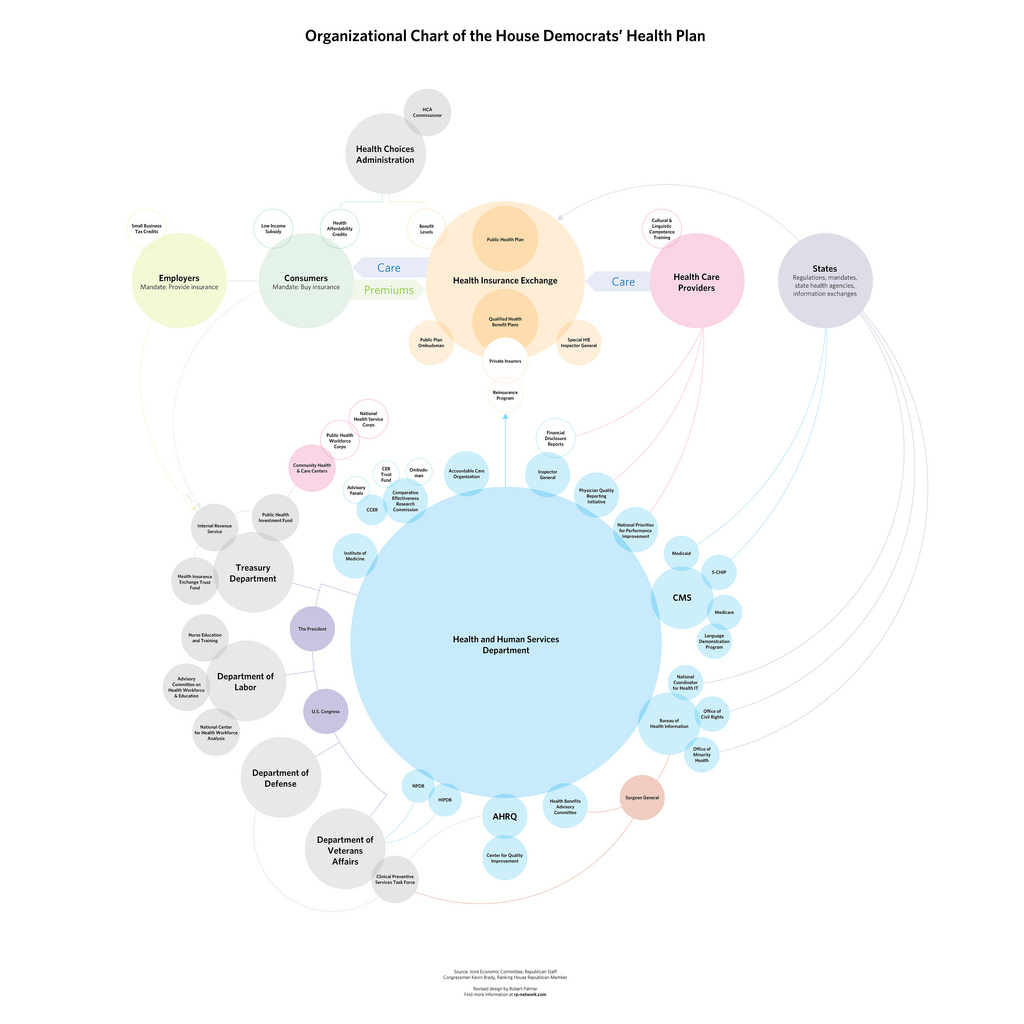

John is drawing on an intellectual tradition goes back to Gibbon, Ibn Khaldun, Polybius, Confucius and Mencius but is mashing it up with modern concepts of social complexity, such as is found in Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies. This makes sense; when members of a ruling class start to behave in an unethical manner, there is a natural reaction by morally vigilant members of the ruling class to check future abuses of power by dividing administrative authority, increasing regulations, creating new watchdogs and erecting balancing countermeasures. This is an increase in complexity that decreases rather than improves efficiency. Society pays more for the same level of effective governance and the creep of corruption will soon require another “re-set” and yet another no-value added increase in complexity as the elite multiplies and seeks their own aggrandizement.

When Robert Wright wrote of “ossifying” societies unable to stand the test of barbarians in the ancient and medieval worlds, in Nonzero:The Logic of Human Destiny, he was explicit that a moral critique often correlated with economic/darwinian fitness. Rome, for example, eschewed adaptive technological innovation due to it’s heavy reliance on inexpensive slave labor. Oligarchic societies fit the moral decay theory because oligarchies focus on the zero sum game of extracting existing wealth from the population instead of creating and accumulating it. The extraction process requires an expensive social architecture of control and this is subject to diminishing returns. At a certain point, any system reaches the tipping point on adding the next level of non-productive complexity and begins to unravel.

What if the historical ratchet could be reversed?

What if the excess complexity could be systemically pared back along with the opportunities for corruption and self-aggrandizement that required countermeasures?

Societies are occasionally capable of moral and political renovation, cases in point, the Glorious Revolution and the Meiji Restoration, both of which tied ancient ideals to new political forms while sweeping away a corrupt elite. The American Revolution period, through the adoption of the US Constitution would be another example of societal transformation. These successes, which involve constitutional reforms and a rejuvenated political economy are essentially of a social contractual nature and are rare. Failure is more common, as with Sulla’s bloody reforms that temporarily got rid of bad actors and rebooted the Roman Republic to an older, more virtuous model but failed to address the fact that the structural flaws of the Republic itself were the problem, not the ambition of Marius.

Things are not yet too far gone. There is much that is wrong with the United States but we have a more resilient and coherent foundation upon which to reconstruct than did the Romans of the 1st century BC.

America has many Mariuses but a better Republic.