[by Mark Safranski / “zen“]

Last week I posted on Human Sacrifice and State-Building, which focused on research findings published in Nature regarding the role of human sacrifice in establishing hierarchical societies. My interest was primarily in the way the gory practices of ISIS today seem to mirror this dynamic from prehistoric, ancient and chiefdom societies. Bogfriend T. Greer helpfully alerted me to the fact that noted scholar and cultural evolutionist, Peter Turchin also blogged regarding this research and took a critical posture. Turchin, also addressed human sacrifice to some degree in his latest book, Ultrasociety, which has been on my list to read for his take on the role of warfare but which I have yet to do.

Turchin’s reasons for blogging this article are different from mine, so I suggest that you read him in full as I intend to comment only on selected excerpts:

Is Human Sacrifice Functional at the Society Level?

An article published this week by Nature is generating a lot of press. Using a sample of 93 Austronesian cultures Watts et al. explore the possible relationship between human sacrifice (HS) and the evolution of hierarchical societies. Specifically, they test the “social control” hypothesis, according to which human sacrifice legitimizes, and thus stabilizes political authority in stratified class societies.

Their statistical analyses suggest that human sacrifice stabilizes mild (non-hereditary) forms of social stratification, and promotes a shift to strict (hereditary) forms of stratification. They conclude that “ritual killing helped humans transition from the small egalitarian groups of our ancestors to the large stratified societies we live in today.” In other words, while HS obviously creates winners (rulers and elites) and losers (sacrifice victims and, more generally, commoners), Watts et all argue that it is a functional feature—in the evolutionary sense of the word—at the level of whole societies, because it makes them more durable.

There are two problems with this conclusion. First, Watts et al. do not test their hypothesis against an explicit theoretical alternative (which I will provide in a moment). Second, and more important, their data span a very narrow range of societies, omitting the great majority of complex societies—indeed all truly large-scale societies. Let’s take these two points in order.

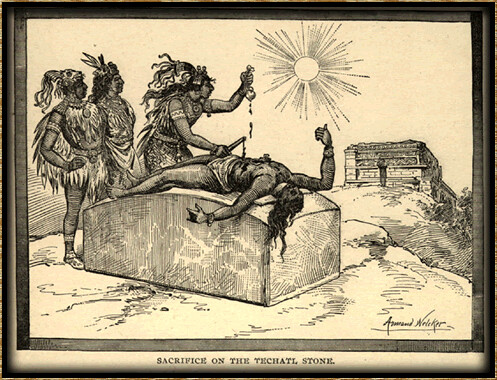

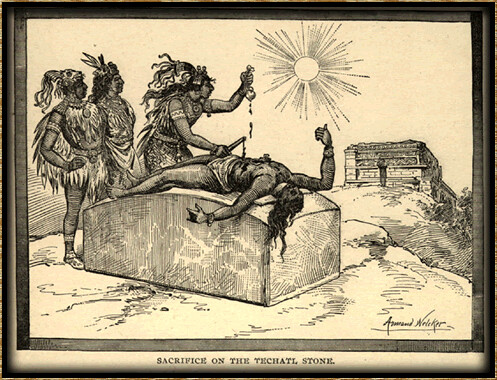

Turchin is correct that study focuses on Austronesian islanders in clan and tribal settings and that’s a pretty narrow of a base from which to extrapolate. OTOH, the pre-Cortez estimated population of the Aztec empire begins at five million on the low end. Estimates of the population of Carthage proper, range from 150,000 to 700,000. That’s sufficiently complex that the Mexica and Carthaginians each established sophisticated imperial polities and yet both societies remained extremely robust practitioners of human sacrifice at the time they were conquered and destroyed.

Maybe a more useful approach than simply expanding the data set would be to ask why human sacrifice disappears earlier in some societies than in others or continues to be retained at high levels of complexity?

An alternative theory on the rise of human sacrifice and other extreme forms of structural inequality is explained in my recent book Ultrasociety ….

….Briefly, my argument in Ultrasociety is that large and complex human societies evolved under the selection pressures of war. To win in military competition societies had to become large (so that they could bring a lot of warriors to battle) and to be organized hierarchically (because chains of command help to win battles). Unfortunately, hierarchical organization gave too much power to military leaders and their warrior retinues, who abused it (“power corrupts”). The result was that early centralized societies (chiefdoms and archaic states) were hugely unequal. As I say in Ultrasociety, alpha males set themselves up as god-kings.

Again, I have not read Ultrasociety, but the idea that war would be a major driver of human cultural evolution is one to which I’m inclined to be strongly sympathetic. I’m not familiar enough with Turchin to know if he means war is”the driver” or “a major driver among several” in the evolution of human society.

Human sacrifice was perhaps instrumental for the god-kings and the nobles in keeping the lower orders down, as Watts et al. (and social control hypothesis) argue. But I disagree with them that it was functional in making early centralized societies more stable and durable. In fact, any inequality is corrosive of cooperation, and its extreme forms doubly so. Lack of cooperation between the rulers and ruled made early archaic states highly unstable, and liable to collapse as a result of internal rebellion or conquest by external enemies. Thus, according to this “God-Kings hypothesis,” HS was a dysfunctional side-effect of the early phases of the evolution of hierarchical societies. As warfare continued to push societies to ever larger sizes, extreme forms of structural inequality became an ever greater liability and were selected out. Simply put, societies that evolved less inegalitarian social norms and institutions won over and replaced archaic despotisms.

The question here is if human sacrifice was primarily functional – as a cynically wielded political weapon of terror by elites – or if that solidification of hierarchical stratification was a long term byproduct of religious drivers. It also depends on what evidence you count as “human sacrifice”. In the upper Paleolithic period, burial practices involving grave goods shifted to include additional human remains along with the primary corpse. Whether these additional remains, likely slaves, concubines or prisoners slain in the burial ritual count as human sacrifices in the same sense as on Aztec or Sumerian altars tens of thousands of years later may be reasonably disputed. What is not disputed is that humans being killed by other humans not by random violence or war but purposefully for the larger needs of a community goes back to the earliest and most primitive reckoning of what we call “society” and endured in (ever diminishing) places even into the modern period.

This also begs the question if burial sacrifices, public executions of prisoners and other ritualistic killings on other pretexts conducted by societies of all levels of complexity are fundamentally different in nature from human sacrifices or if they are all subsets of the same atavistic phenomena binding a group through shared participation in violence.

….The most complex society in their sample is Hawaii, which is not complex at all when looked in the global context. I am, right now, analyzing the Seshat Databank for social complexity (finally, we have the data! I will be reporting on our progress soon, and manuscripts are being prepared for publication). And Hawaii is way down on the scale of social complexity. Just to give one measure (out of >50 that I am analyzing), polity population. The social scale of Hawaiian chiefdoms measures in the 10,000s of population, at most 100,000 (and that achieved after the arrival of the Europeans). In Afroeurasia (the Old World), you don’t count as a megaempire unless you have tens of millions of subjects—that’s three orders of magnitude larger than Hawaii!

Why is this important? Because it is only by tracing the trajectories of societies that go beyond the social scale seen in Austronesia that we can test the social control hypothesis against the God-Kings theory. If HS helps to stabilize hierarchical societies, it should do so for societies of thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions, tens of millions, and so on. So we should see it persist as societies grow in size.

Well, human sacrifice persisted into the classical period of Greece and Rome, though becoming infrequent and eventually outlawed, though only during the last century of the Roman republic. That’s a significant level of complexity, Rome having become the dominant power in the Mediterranean world a century earlier. Certainly human sacrifice did not destabilize the Greeks and Romans, though the argument could be made that it did harm Sparta, if we count Spartan practices of infanticide for eugenic reasons as human sacrifice.

What muddies the waters here is the prevalence of available substitutes for human sacrifice – usually animal sacrifice initially – that competed and co-existed with human sacrifice in many early societies for extremely long periods of time. Sometimes this readily available alternative was sufficient to eventually extinguish human sacrifice, as happened with the Romans but other times it was not, as with the Aztecs. The latter kept their maniacal pace of human sacrifice up to the end, sacrificing captured Spanish conquistadors and their horses to the bloody Sun god. Human sacrifice did not destabilize the Aztecs and it weakened their tributary vassals but the religious primacy they placed on human sacrifice and the need to capture prisoners in large numbers rather than kill them in battle hobbled the Aztec response to Spanish military assaults.

Comments? Questions?