[ by Charles Cameron — “homegrown” jihad ]

.

Jihad Joe: Americans who go to war in the name of Islam

by JM Berger

Potomac Books, Inc, 2011, hard back, $29.95

*

The title by itself is striking — Jihad Joe – and captures nicely the somewhat surreal blend of the normal and the utterly strange that we encounter when we think about “Americans who go to war in the name of Islam” – the subtitle and topic of JM Berger‘s book. And think about them, know a bit about them, we should.

The big question, of course, is Why?

Berger writes early on of young men who gather “to focus their rage through a religious filter” and while noting that jihadists comes from varied backgrounds and travel for varied reasons, correctly zeroes in on the sense of obligation that a jihadist interpretation of Islam imposes:

While all major religions have rules that limit or justify war, a small but significant minority of Muslims believe that under the correct circumstances, war is a fundamental obligation for everyone who shares the religion of Islam. When war is carried out according to the rules, it is called military jihad or simply jihad. [emphasis mine]

The rage may spring from many sources, social, economic, political, but when religion is used to focus it, as Berger nicely puts it, that obligation is what provides divine legitimacy — and the promise of miracles, martydom and a paradisal afterlife – and the sense of serving a higher purpose, to otherwise quieter lives.

*

Berger starts at the beginning. After a brief mention of the presence of many Muslims under slavery, two early and distinctly American expressions of Islam (the Moorish Science Temple and the Nation of Islam), and the beginnings of Muslim Brotherhood activity as Egyptian and other Muslim immigrants brought more orthodox strands of Islam to the States, Berger alerts us to the idea that Americans leaving to fight jihad may have deeper roots than we think.

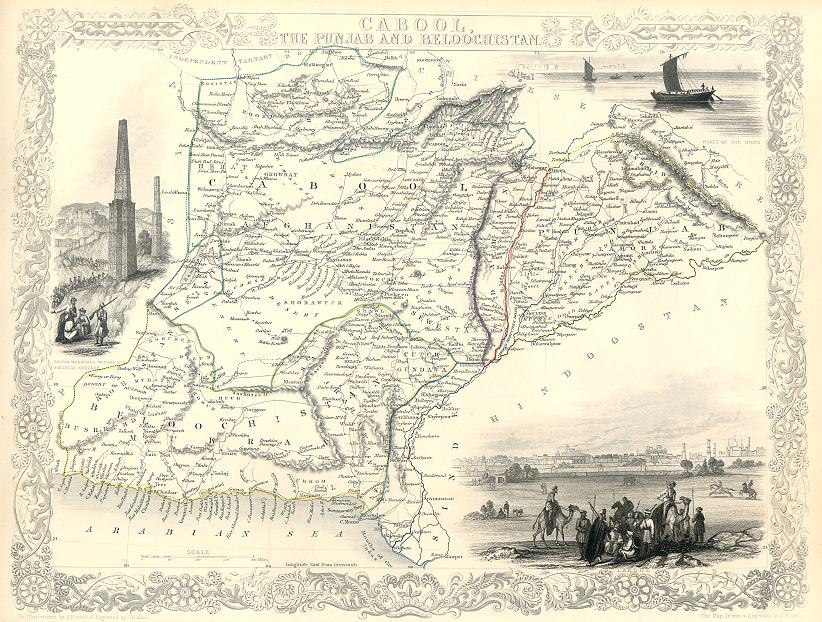

Bin Laden‘s mentor Abdullah Azzam, for instance, was in the US in the 1980s appealing for Americans to help the mujahideen in their resistance to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan – a cause supported by President Reagan, who took tea with muj leaders for discussion and photo op, and by the wily Charlie Wilson of Charlie Wilson’s War. Azzam’s calls for volunteers were successful:

No one kept track of how many Americans answered the call, and no one in or out of the U.S. Government would venture a guess on the record. More than 30 documented cases were examined for this book. Based on court records and intelligence documents, a conservative estimate might be that a minimum of 150 American citizens and legal residents went to fight the Soviets.

Implications for today: this has been happening for a long time, it’s not something Anwar al-Awlaki invented just yesterday — and there have been times when the US was no too displeased at such activities.

Azzam’s appeal was precisely to the sense of a general, compulsory obligation for Muslims – fard ayn in Arabic – buttressed by tales of the miraculous and promises of paradise. I emphasize these points because their appeal is real. The day Al-Qaida was founded, an American was present, Mohammed Loay Bayazid, aka Abu Rida al Suri, and it was his reading of Azzam’s account of miracles among the jihadists in Afghanistan – apparent supernatural protection from and/or paralysis of superior forces, the “odor of sanctity” on martyrs’ bodies – that turned him from a not very pious Muslim into a volunteer jihadist. You can read the stories yourself — Azzam’s book is now available for download, in English, on the web.

I’m focusing in on the religious element because that’s my area, others will comment better than I on the military or historical aspects that Berger deals with. But Berger makes it clear that from its inception, Al-Qaida numbered Americans among its higher echelons, and bin Laden was “strangely enamored of Americans and people who had spent time in the United States” – if only for the very practical reason that their passports allowed them access most anywhere.

*

The first act of violence on American soil generally attributed to AQ, Berger tells us, was the 1990 killing of Rashad Khalifa in Tucson, AZ. Khalifa was the numerologically inclined leader of a Tucson mosque and translator of the Qur’an whose apocalyptic date-setting (2280 CE) I mentioned in my Zenpundit post Apocalypse Not Yet? a week ago.

Khalifa’s story leads into that of Al Fuqra, a group that Berger describes in some detail, writing of their “rural compounds and small private villages” and their “covert paramilitary training grounds” and noting that while they have been implicated in “at least thirty-four incidents … from bombings to kidnappings to murder … the government has never moved against the group in an organized manner.”

Berger turns next to the blind Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman and his followers, soon joined by the AQ-trained bomb-maker Ramzi Yousef, and the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center – which failed to topple the towers — leaving the task for Mohammed Atta to complete in 2001 under bin Laden’s command

1992 sees several thousand US troops in Arabia given briefings on Saudi culture – largely a matter of Wahhabist Islam – and four-day passes to visit Mecca at Saudi expense were available for converts. As the Bosnian crisis began to unfold, ex-military Muslims converted by these means formed a natural pool for recruitment as jihadists to defend their Muslim brothers against ethnic cleansing and genocide at the hands of their Serb neighbors.

With the combination of the first WTC bombing and the Bosnian jihad, the “far enemy / near enemy” combo was in place: jihad could draw on both local and global events to fuel its global plans, and find both local and targets to take down…

By the beginning of the 1990s, America was in AQ’s sights, though AQ was barely known to a handful of Americans. The 1993 Black Hawk Down incident in Mogadishu featured AQ-trained forces, and the Nairobi and Dar es Salaam embassy attacks were soon in the planning stages. In 1996, bin Laden publishes his declaration of war on America, and the CIA put together a first plan to kidnap him…

*

Anwar al-Awlaki enters the picture around this time, a complex man Berger calls “a study in contradictions” – “a gifted speaker who was capable of moving men to action”.

If the power of religion to focus rage, and the concept of jihad as a compulsory obligation, fard ayn, are two of our first take-aways from Berger’s book, here is a third: rhetoric is the tool that transforms the curious (pious or not so much) into the committed. Anwar al-Awlaki had “a powerful cocktail of skills” but they boil down to this: the ability to talks Islam casually, in the American manner, to American kids — in American English, in a way that appears pious and scholarly, presents jihad as both obligation and adventure, and moves them to action…

Three of the 9-11 hijackers were al-Awlaki contacts… Nidal Hasan, the army psychiatrist who massacred his fellow soldiers at Fort Hood… Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the suspected “underwear bomber”… Faizal Shazad, the Times Square bomber… the list of those who have known and been influenced by al-Awlaki goes on…

The history of AQ by now is well known, covered in such books as Lawrence Wright‘s The Looming Tower and Peter Bergen‘s The Longest War, so Berger can concentrate on the “home grown” side of things, featuring — alongside al-Awlaki — his clumsier precursor the AQ propagandist Adam Gadahn, and paying considerable attention to another less-than-widely reported aspect of the jihad – the Pakistani Lashkar-e-Taiba group and its ISI-assisted 2008 attack on Mumbai, India, for which the intelligence scouting was done by the Pakistani-American sometime DEA agent David Headley, and the subsequent planning of an attack in Denmark…Berger turns next to Somalia and al-Shabab – but you get the drift, he is offering us a thoroughgoing, fully researched tour of the various Americans and groups joined by Americans across the world, involved in waging jihad, against scattered local enemies, or against the “far enemy” – the United States.

*

Berger’s work is detail-packed and focused, and a useful resource for that reason alone. But it is also and specifically the work of someone who has read and talked with and listened to the people he is writing about, and his work carries their voices embedded in his own commentary. It thus joins such works as Jessica Stern‘s Terror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants Kill and Mark Juergensmeyer‘s similarly named and similarly excellent Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence.

Bringing us up to date, Berger offers an overview of jihadist use of the internet, paying special attention to English-language sites – Islamic Awakening, Revolution Muslim — emphasizing the peripheral nature of “forum” activities, but also crediting them as an active doorway to recruitment. Zach Chesser, Samir Khan, Jihad Recollections and Inspire magazine, they’re all here. Read Berger’s recent blog post on “gamification” after this chapter, follow him at @intelwire, and you’ll be ongoingly up to date on his thought…

Berger closes with a look at future prospects. The opening of this chapter – an overview of the history so far covered – speaks volumes:

The journey of the American jihadist spans continents and decades. Americans of every race and cultural background have made the decision to take up arms in the name of Islam and strike a blow for what they believed to be justice.

Many who embarked on this journey took their first steps for the noblest of reasons – to lay their lives on the line in defense of people who seemed defenseless. But some chose to act for baser reasons – anger, hatred of the “other,” desire for power, or an urge towards violence.

In the early days of the movement, it was possible to be a jihadist and still be a “good” American…

Berger neither condemns nor excuses: he sees, he asks, he researches, he reports. His observations of the current situation can thus be trusted to be driven by insight rather than ideology – not the most common of stances, but one we very much need.

He pinpoints as the first element that almost all American jihadists have in common as “an urgent feeling that Muslims are under attack”. Foreign policy implications? Yes indeed – but Berger is also looking to the Muslim community to take an approach less focused on what he terms a “litany of grievances” – valid though some of them may be – which in effect helps perpetuate a “counterproductive narrative” of how the US views and treats Muslims.

Once a narrative that America is at war with Islam is established, the argument for jihad as fard ayn can be made – and all manner of shame, frustrations, rage, violent tendencies, alienation and idealism can be unleashed under the jihadist banner.

Berger’s conclusion:

We must preserve the constitutional rights and basic human respect due to American Muslims while changing the playing field to create conditions in which extremism cannot thrive. These goals are not mutually exclusive – they are independent.

If principle and pragmatism are not enough reason to change the tone of the conversation, there isx one more thing to consider. It would be not only dangerous but shameful to prove that our enemies were right about us all along.

Berger’s is a book to read, certainly — and more significantly perhaps, a book to admire.