The Abbottabad raid: tellings and retellings

Thursday, May 5th, 2011[ by Charles Cameron ]

*

My friend Bryan Alexander‘s book, The New Digital Storytelling: Creating Narratives with New Media, hit the shelves a short while ago (recommended) — and this month Bryan is exploring the various forms of digital story-telling on his new digital storytelling blog.

I’m interested in narrative, too – even when it isn’t digital – because it’s the prime way in which we humans figure out what’s going on around us…

Here, then, are two “tellings and retellings” of the Abbottabad raid and the death of Osama bin Laden.

.

1. The fog of war

In his first briefing on bin Laden’s death from the White House, John Brennan, Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counter-Terrorism, dismissed bin Laden with the words, “I think it really just speaks to just how false his narrative has been over the years.”

Narrative is important, and the narrative John Brennan was proposing as a corrective to bin Laden’s version went as follows:

here is bin Laden, who has been calling for these attacks, living in this million dollar-plus compound, living in an area that is far removed from the front, hiding behind women who were put in front of him as a shield. I think it really just speaks to just how false his narrative has been over the years. And so, again, looking at what bin Laden was doing hiding there while he’s putting other people out there to carry out attacks again just speaks to I think the nature of the individual he was.

A writer in the Atlantic commented today:

And that’s the message our counterterrorism officials would, I expect, like the world — and especially any potential followers of al-Qaeda’s anti-American ideology — to get about our newly vanquished enemy, responsible to the single deadliest attack on American soil. The leader of the terrorist group was soft, a coward in the end who hid behind a woman’s skirts like a little girl, having grown accustomed to living in luxury in a mansion. Almost everything about this narrative seemed calculated to diminish any possible perception of strength or masculinity in bin Laden’s reaction to the raid by an elite team of U.S. Navy Seals — men who are in contrast among the most mythic and valorized in our armed forces, known for slogans like “pain is just weakness leaving the body.”

But just a day after Brennan’s briefing, the President’s Press Secretary, Jay Carney, gave a second briefing, in which he revised the official narrative, saying:

Well, what is true is that we provided a great deal of information with great haste in order to inform you and, through you, the American public about the operation and how it transpired and the events that took place there in Pakistan. And obviously some of the information was — came in piece by piece and is being reviewed and updated and elaborated on.

.

So what I can tell you, I have a narrative that I can provide to you on the raid itself, on the bin Laden compound in Pakistan.

I have a narrative…

The revised narrative featured an unarmed bin Laden in a far from palatial house with no visible air-conditioning, who didn’t in fact use a woman as a human shield… all of which “really just speaks to just how false” Brennan’s own original narrative was.

But then – you don’t believe everything you read in the press, do you? And besides, the first news reports of almost any big story are almost invariably inaccurate, it takes time for clarity to emerge… which adds up to the idea that it’s not so easy to distinguish between how the world actually spins — and how the world is spun.

So that’s a telling and retelling of the Abbottabad raid in “real life” as transmitted to us by various media and recorded on the web…

.

2: The twitter-stream and the analyst

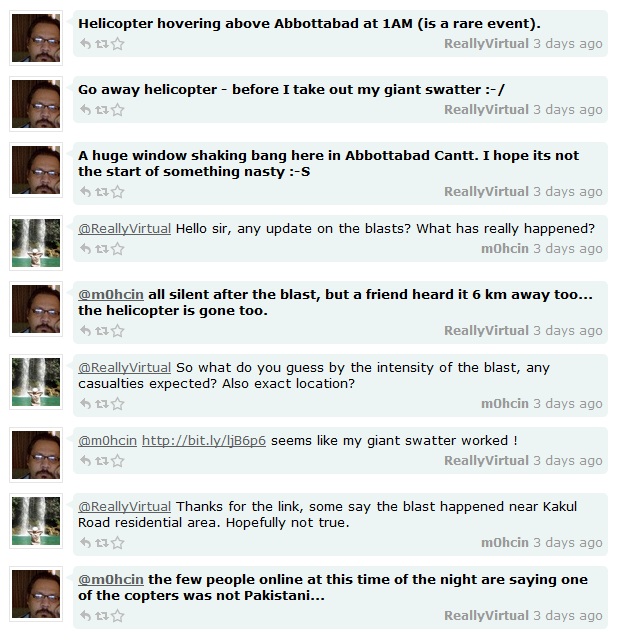

A little earlier a more “purely” digital version of the story – no less confused by the “fog” that inevitably surrounds the reporting of highly volatile situations – had emerged quite spontaneously via Twitter, when the delightfully-named ReallyVirtual (an IT specialist who had moved to Abbottabad for some peace and quiet) was kept awake by the noise of helicopters overhead and sounds of explosions, and tweeted a couple of late-night friends… and a stream of tweets began which quickly led to an almost thousandfold spike in Yahoo searches on bin Laden, and bin Laden related searches occupying all top twenty spots on Google trends…

You might call that spontaneous, distributed story-telling – but it’s also the raw material for a collated and curated twitter narrative, using Chirpstory, a tool for curating and presenting stories from the twitter-stream:

We’re not done yet…

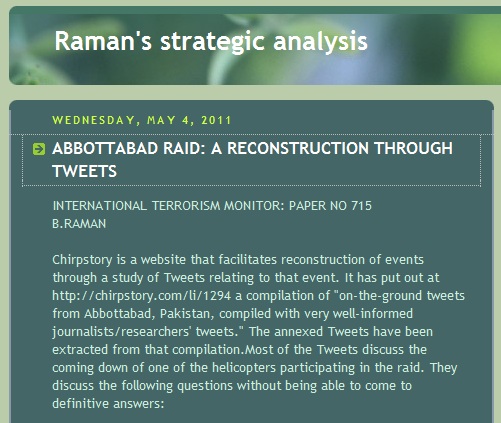

That in turn provides grist for the analytic mill of B Raman, a highly-regarded Indian analyst, blogger, and former chief of counter-terrorism with India’s R&AW intelligence agency – who winnowed out the chaff and added in his own commentary to create a denser, tighter analytic narrative of his own:

To my way of thinking, the spontaneous twitter-stream version, the Chirpstory adaptation and B. Raman’s midrash on it are at least as interesting as the successive White House narratives…

.

3. Further reading:

Also relevant to our narrative here, and your own readings on the topic of our tale:

How the Bin Laden Announcement Leaked Out

Bin Laden Reading Guide: How to Cut Through the Coverage

process of political radicalization and how do theyinfluence a person or group’s choice of means (such as violence) to achieve political ends? How do stories influence bystanders’ response to conflict? Is it possible to measure how attitudes salient to security issues are shaped by stories?

process of political radicalization and how do theyinfluence a person or group’s choice of means (such as violence) to achieve political ends? How do stories influence bystanders’ response to conflict? Is it possible to measure how attitudes salient to security issues are shaped by stories?