Review: The Rule of the Clan

Wednesday, April 20th, 2016[by Mark Safranski / “zen“]

Rule of the Clan by Mark Weiner

I often review good books. Sometimes I review great ones. The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals about the Future of Individual Freedom by Mark S. Weiner gets the highest compliment of all: it is an academic book that is clearly and engagingly written so as to be broadly useful.

Weiner is Professor of Law and Sidney I. Reitman Scholar at Rutgers University whose research interests gravitate to societal evolution of constitutional orders and legal anthropology. Weiner has put his talents to use in examining the constitutional nature of a global phenomena that has plagued IR scholars, COIN theorists, diplomats, counterterrorism experts, unconventional warfare officers, strategists, politicians and judges. The problem they wrestle with goes by many names that capture some aspect of its nature – black globalization, failed states, rogue states, 4GW, hybrid war, non-state actors, criminal insurgency, terrorism and many other terms. What Weiner does in The Rule of the Clan is lay out a historical hypothesis of tension between the models of Societies of Contract – that is Western, liberal democratic, states based upon the rule of law – and the ancient Societies of Status based upon kinship networks from which the modern world emerged and now in places has begun to regress.

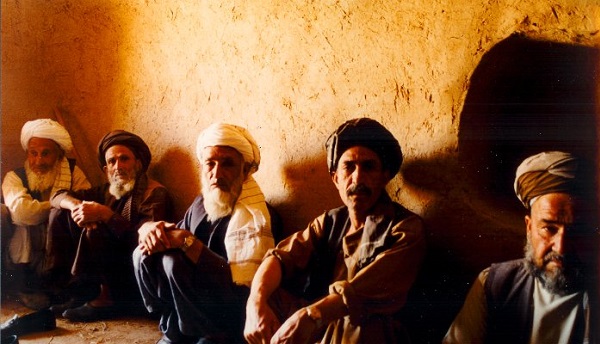

Weiner deftly weaves the practical problems of intervention in Libya or counterterrorism against al Qaida with political philosophy, intellectual and legal history, anthropology, sociology and economics. In smooth prose, Weiner illustrates the commonalities and endurance of the values of clan and kinship network lineage systems in societies as diverse as Iceland, Saudi Arabia, Kenya, India and the Scottish highlands, even as the modern state arose around them. The problem of personal security and the dynamic of the feud/vendetta as a social regulator of conduct is examined along with the political difficulties of shifting from systems of socially sanctioned collective vengeance to individual rights based justice systems. Weiner implores liberals (broadly, Westerners) not to underestimate (and ultimately undermine) the degree of delicacy and strategic patience required for non-western states transitioning between Societies of Status to Societies of Contract. The relationship between the state and individualism is complicated because it is inherently paradoxical, argues Weiner: only a state with strong, if limited, powers creates the security and legal structure for individualism and contract to flourish free of the threat of organized private violence and the tyranny of collectivistic identities.

Weiner’s argument is elegant, well supported and concise (258 pages inc. endnotes and index) and he bends over backwards in The Rule of the Clan to stress the universal nature of clannism in the evolution of human societies, however distant that memory may be for a Frenchman, American or Norwegian. If the mores of clan life are still very real and present for a Palestinian supporter (or enemy) of HAMAS in Gaza, they were once equally real to Saxons, Scots and Franks. This posture can also take the rough edges off the crueler aspects of, say, life for a widow and her children in a Pushtun village by glossing over the negative cultural behaviors that Westerners find antagonizing and so difficult to ignore on humanitarian grounds. This is not to argue that Weiner is wrong, I think he is largely correct, but this approach minimizes the friction involved in the domestic politics of foreign policy-making in Western societies which contain elite constituencies for the spread of liberal values by the force of arms.

Strongest recommendation.