History Will Judge Only if We Ask the Right Questions

Wednesday, April 18th, 2012

Thomas Ricks of CNAS recently had a historically-minded post at his Best Defense blog at Foreign Policy.com:

What Tom would like to read in a history of the American war in Afghanistan

I think I’ve mentioned that I can’t find a good operational history of the Afghan war so far that covers it from 2001 to the present. (I actually recently sat on the floor of a military library and basically went through everything in its stacks about Afghanistan that I hadn’t yet read.)

Here are some of the questions I would like to see answered:

–What was American force posture each year of the war? How and why did it change?

–Likewise, how did strategy change? What was the goal after al Qaeda was more or less pushed in Pakistan in 2001-02?

–Were some of the top American commanders more effective than others? Why?

–We did we have 10 of those top commanders in 10 years? That doesn’t make sense to me.

–What was the effect of the war in Iraq on the conduct of the war in Afghanistan?

–What was the significance of the Pech Valley battles? Were they key or just an interesting sidelight?

–More broadly, what is the history of the fight in the east? How has it gone? What the most significant points in the campaign there?

–Likewise, why did we focus on the Helmand Valley so much? Wouldn’t it have been better to focus on Kandahar and then cutting off and isolating Oruzgan and troublesome parts of the Helmand area?

–When did we stop having troops on the ground in Pakistan? (I know we had them back in late 2001.) Speaking of that, why didn’t we use them as a blocking force when hundreds of al Qaeda fighters, including Osama bin Laden, were escaping into Pakistan in December 2001?

–Speaking of Pakistan, did it really turn against the American presence in Afghanistan in 2005? Why then? Did its rulers conclude that we were fatally distracted by Iraq, or was it some other reason? How did the Pakistani switch affect the war? Violence began to spike in late 2005, if I recall correctly — how direct was the connection?

–How does the war in the north fit into this?

–Why has Herat, the biggest city in the west, been so quiet? I am surprised because one would think that tensions between the U.S. and Iran would be reflected at least somewhat in the state of security in western Afghanistan? Is it not because Ismail Khan is such a stud, and has managed to maintain good relations with both the Revolutionary Guard and the CIA? That’s quite a feat.

Ricks of course, is a prize winning journalist and author of best selling books on the war in Iraq, including Fiasco and he blogs primarily about military affairs, of which Ricks has a long professional interest and much experience. Ricks today is a think tanker, which means his hat has changed from reporter to part analyst, part advocate of policy. That’s fine, my interest here are in his questions or rather in how Ricks has approached the subject.

First, while there probably ought to be a good “operational history” written about the Afghan War – there’s a boatload of dissertations waiting to be born – I think that in terms of history, this is the wrong level at which to begin asking questions. Too much like starting a story in the middle and recounting the action without the context of the plot, it skews the reader’s perception away from motivation and causation.

I am not knocking Tom Ricks. Some of his queries are important – “What was the effect of the war in Iraq on the conduct of the war in Afghanistan?” – rises to the strategic level due to it’s impact and the light it sheds on national security decision making during the Bush II administration, which I suspect, will not look noble when it is revealed in detail because it almost never is, unless you are standing beside Abraham Lincoln as he signs the Emancipation Proclamation. Stress, confusion, anger and human frailty are on display. If you don’t believe me, delve into primary sources for the Cuban Missile crisis sometime. Or the transcripts of LBJ and NIxon. Exercise of power in the moment is uncertain and raw.

But most of the questions asked by Ricks were “operational” – interesting, somewhat important, but not fundamental. To understand the history of our times, different questions will have to be asked in regard to the Afghan War. Here are mine for the far off day when documents are declassified:

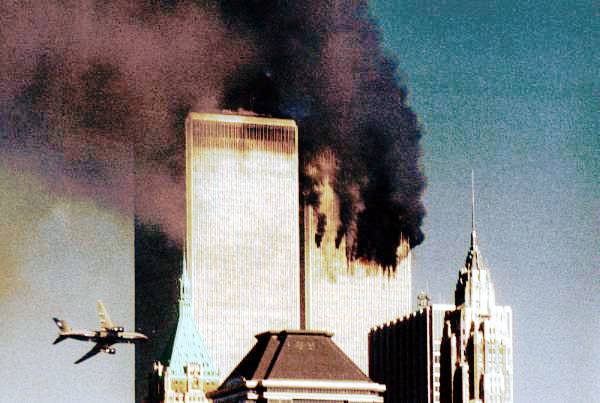

What was the evolution of the threat assessment posed by Islamist fundamentalism to American national security by the IC from the Iranian revolution in 1979 to September 11, 2001? Who dissented from the consensus? What political objections or pressures shaped threat assessment?

What did American intelligence, military and political officials during the Clinton, Bush II and Obama administrations know of the relationship between the ISI and al Qaida and when did they know it?

What did American intelligence, military and political officials during the Clinton, Bush II and Obama administrations know of the relationship between Saudi intelligence, the House of Saud and al Qaida and when did they know it?

What did American intelligence, military and political officials during the Clinton, Bush II and Obama administrations know of the relationship between the Taliban and al Qaida and when did they know it?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did Saudi leverage over global oil markets effect American strategic decision making?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did Pakistani nuclear weapons effect American strategic decision making?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did the “Iraq problem” effect American strategic decision making?

In the aftermath of 9-11, how did nuclear terrorism threat assessments effect American strategic decision making? Did intelligence reports correlate with or justify the policy steps taken?

Who made the call on tolerating Pakistani sanctuaries for al Qaida and the Taliban and why?

Was there a net assessment of the economic effects of a protracted war in Afghanistan or Iraq made and presented to the POTUS? If not, why not?

Why was a ten year war prosecuted with a peacetime military and a formal declaration of war eschewed?

How did the ideological convictions of political appointees in the Clinton, Bush II and Obama impact the collection and analysis of intelligence and execution of war policy?

Who made the call for tolerating – actually financially subsidizing – active Pakistani support for the Taliban’s insurgency against ISAF and the Government of Afghanistan and why?

What counterintelligence and counterterrorism threat assessments were made regarding domestic Muslim populations in the United States and Europe and how did these impact strategic decisions or policy?

What intelligence briefs or other influences caused the incoming Obama administration to radically shift positions on War on Terror policy taken during the 2008 campaign to harmonize with those of the Bush II administration?

What discussions took place at the NSC level regarding the establishment of a surveillance state in the “Homeland”, their effect on our political system and did any predate September 11, 2001 ?

What were the origins of the Bush administration’s judicial no-man’s land policy regarding “illegal combatants” and “indefinite detention”, the recourse to torture but de facto prohibition on speedy war crimes trials or capital punishment?

The answers may be a bitter harvest.