Updating the Apocalypse

Tuesday, May 15th, 2012[ by Charles Cameron — four shifts in apocalyptic thinking, us & them, sacred and secular ]

.

Every time something significant happens in Europe or the Middle East, those who have worked out their apocalyptic timelines ahead of time have to make appropriate adjustments.

1.

Today, the Christian apocalyptic writer Joel Richardson took note of recent events in Europe in a piece entitled The Collapse of the Euro = The Collapse of the Euro-Centered End-Time Perspective? and asked:

as the collapse of the Euro monetary unity appears to loom over all of us, how will such an global earthquake affect the popular, but equally collapsing Euro-centered perspective on the end times?

Joel may be onto something, we may be on the verge of a major shift in Christian end times emphasis — away from Europe and towards Joel’s Islamic Antichrist theory, as explored in his book The Islamic Antichrist: The Shocking Truth about the Real Nature of the Beast and his forthcoming Mideast Beast: The Scriptural Case For an Islamic Antichrist.

2.

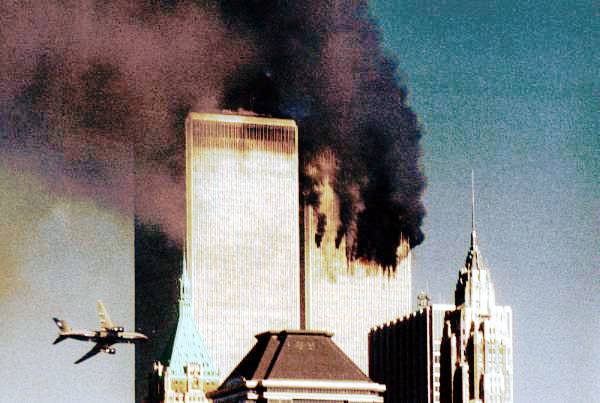

I’ve put a screen shot at the top of this post from an end times video featuring Europe as the evil empire and the Pope as Antichrist – it’s a brilliant graphic pairing that illustrates the older theory visually and viscerally, and should you so wish, you can watch the whole thing here. Note also the comment from SyriacBoy10 below the video:

In the Bible and the Quran, it is said that the Antichrist will come from Europe which is expected to be in this generation due to the signs and global disasters.

Just what place names in scriptures might refer to just what places or entities in modern or far future times is always a matter of interpretation — as Joel himself neatly demonstrated with a variety of “biblical” maps in his Prophezine post Where is Magog, Meshech and Tubal?

And for that matter, is our Coptic friend speaking of the Antichrist in the Qur’an, or the Dajjal? The two are commonly inflated, which gets a bit confusing after a while…

3.

And here’s Joel on failed predictions of the EU as the pivotal demonic empire of the last days in prophecy:

Nearly 20 years ago, I intently watched as a very popular Christian television prophecy teacher declared, “The present formation of the European Union is literally the fulfillment of Bible prophecy right before our eyes!”

According to this teacher, the creation of the European Union represented a biblically prophesied revived Roman Empire. Because the last-days empire of the Antichrist, as described in the books of Daniel and Revelation, is portrayed as a 10-nation alliance, this teacher confidently declared that when the number of EU member states reached 10, this would signal the imminent return of Jesus Christ.

Soon, the number of EU member states reached the magic number 10, just as this teacher had predicted. Then the number reached 11, and then 12. Soon there were 20. Today there are 27 member states. The teacher’s very confident predictions failed.

4.

As it happens, I correspond with Joel on occasion and like the man, despite our holding very different theological opinions. In particular, I like to quote this passage from his description of an interview he gave on NPR:

I explained to my host that unless a supernatural man bursts forth from the sky in glory, there is absolutely nothing that the world needs to worry about with regard to Christian end-time beliefs. Christians are called to passively await their defender. They are not attempting to usher in His return. Muslims, on the other hand, are actively pursuing the day when their militaristic leader comes to lead them on into victory. Many believe that they can usher in his coming.

I’d be interested to know what GEN Boykin would make of that…

5.

All in all, I see four trends in apocalyptic thinking at the present time.

First, there’s a trend, suggested by Joel Richardson in his articles linked above, away from an earlier Eurocentric focus of end times interpretation, and towards his own view of Islam – and of the Mahdi (awaited by many Muslims) as Antichrist.

Second, there’s a trend noted by another occasional correspondent of mine, Julie Ingersoll, in one of her two recent articles on Kirk Cameron in Religion Dispatches – more precisely, a theological shift:

from the larger premillennialist evangelical world that he depicted in Left Behind to the postmillennialist dominion theology of the Reconstructionists.

Third, It seems to me that there’s a trend away from the “soon expectation” of the Mahdi of President Ahmadinejad in Iran, as the Supreme Jurisprudent, Khamenei, withdraws his support from his President and Ahmadinejad enters his lame duck phase…

And finally, there are mild signs that apocalyptic itself and religious motives more generally are slowly entering the discourse of the strategically minded, including those whose secular worldviews have hitherto all too often led them to dismiss both religious and apocalyptic drivers as irrational and unserious.

Columbia’s upcoming Hertog Global Strategy Initiative with its focus this year on Religious Violence and Apocalyptic Movements, which I mentioned recently, is one such sign – another is the attention paid to Khorasan — a name with strong Mahdist associations — in a post at the Long Wars Journal today.

6.

Luckily, we have Richard Landes‘ massive, brilliant Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience to educate us in the bewildering profusion of forms, both secular and sacred, that millennial hopes and fears can take.

And with Israel’s departing Shin Beth chief calling PM Netanyahu “messianic” – using the same term Netanyahu used for Ahmedinajad – it’s about time, too.