The Wearing Thin of the Nation State

Monday, September 16th, 2019[ by Charles Cameron — following on from Climate change & its impacts, rippling out across all our futures, 2 on national sovereignty and climate migration — with Hakim Bey’s TAZ and more ]

.

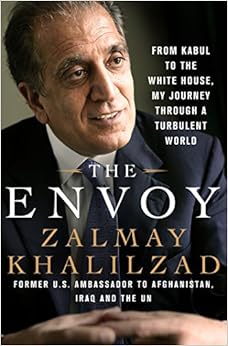

Three books by Peter Lamborn Wilson

**

Two instances of our theme — The Wearing Thin of the Nation State — crossed my bows in utterly unrelated posts via Academia today, and they make a fine DoubleQuote:

From John Sullivan‘s Criminal Enclaves: When Gangs, Cartels or Kingpins Try to Take Control:

Criminal enclaves are areas where lawbreakers (gangs, cartels, criminal warlords) exert political and social control. Essentially these areas are “other governed spaces.” The state may or may not be absent — although its hold is certainly challenged — but other informal governance structures, such as gangs, wield substantial political influence or control. These other governed spaces can range in size from neighborhoods, barrios or favelas (i.e., failed communities) to failed or feral cities — such as Brazil’s notorious City of God favela or Ciudad Juárez during the height of cartel control or Veracruz and Acapulco — to failed states or regions, such as an entire nation — extremely rare — or a substate region such as Mexico’s Tamaulipas. These enclaves are essentially incubators of state change or transition as described by Charles Tilly in his essay “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime.” This process of criminal challenges to states can be described as criminal insurgency, where bands of outlaws erode sovereignty while potentially altering the nature of states. In addition to geographic scope, criminal enclaves can vary in their degree of control over governance. They can exist as parallel states, exerting control over some functions (i.e., taxation, monopoly of violence and justice, and the provision of social goods), while the state still retains control over others.These enclaves could also fully supplant the state when it is absent or lacks solvency, which I define as the sum of legitimacy and capacity. They could also form a hybrid where criminal networks and corrupt politicians cooperate to extract wealth and wield power (as is the case in narco-cities or mafia states).

I’d like to offer, by way of comparative, this excerpt from Abbe Mowshowitz as quoted in Bill Benzon‘s and his

Virtual Feudalism in the Twenty-First Century:

Absent a sense of loyalty to persons or places, virtual organizations distance themselves—both geographically and psychologically—from the regions and countries in which they operate. This process is undermining the nation-state, which cannot continue indefinitely to control virtual organizations. A new feudal system is in the making, in which power and authority are vested in private hands but which is based on globally distributed resources rather than on possession of land. The evolution of this new political economy will determine how we do business in the future.

That’s my DoubleQuote.

**

That’s interesting, I think — but what’s even more so is the quote that initially caught my eye in Bill B‘s paper:

In 2017, Denmark became the first nation to formally create a diplomatic post to represent its interests beforecompanies such as Facebook and Google. After Denmark determined that tech behemoths now have as much power as many governments — if not more — Mr. Klynge was sent to Silicon Valley.“What has the biggest impact on daily society? A country in southern Europe, or in Southeast Asia, or Latin America, or would it be the big technology platforms?” Mr. Klynge said in an interview last month at a cafe in central Copenhagen during an annual meeting of Denmark’s diplomatic corps. “Our values, our institutions, democracy, human rights, in my view, are being challenged right now because of the emergence of new technologies.” He added, “These companies have moved from being companies with commercial interests to actually becoming de facto foreign policy actors.”

That’s quoted from Adam Satariano, The World’s First Ambassador to the Tech Industry.

Ambassador to the Tech Industry? Ambassador to the Tech Industry, okay. The ground is shifting under our feet.

**

Detail from Ceasefire’s account of the Temporary Autonomous Zone

Peter Lamborn Wilson aka Hakim Bey, with his interest in the Barbary Corsairs, must have been one of the earlier writers to discuss what he termed Temporary Autonomous Zones — TAZ for short — and its no surprise he’s an eccentric scholar of Islamic Heresy and the Margins of Islam! And what a life he’s led — studying tantra with Ganesh Baba in India, in Pakistan “mixing with princes, Sufis, and gutter dwellers”, an associate in Iran of Henry Corbin, editor of the journal Sophia Perennis under the guidance of Seyyed Hossein Nasr, house-mate in NYC with William Burroughs — though let’s not forget some far darker stuff [cf “Bey’s endorsement of adults having sex with children”, Wikipedia].

**

Narcos in Mexico to Bill Burroughs in Tangiers and NYC isn’t too great a hop: life on the margins is liminal by definition, disruptive — and disruption is what all of our examples above have in common.

Bey on the TAZ:

Getting the TAZ started may involve tactics of violence and defense, but its greatest strength lies in its invisibility–the State cannot recognize it because History has no definition of it. As soon as the TAZ is named (represented, mediated), it must vanish, it will vanish, leaving behind it an empty husk, only to spring up again somewhere else, once again invisible because undefinable in terms of the Spectacle. The TAZ is thus a perfect tactic for an era in which the State is omnipresent and all-powerful and yet simultaneously riddled with cracks and vacancies.

How will the nation state respond, adapt?